The iconic American leaders who were once refugees

Many people have fled persecution, war or political oppression to create something extraordinary out of their lives

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

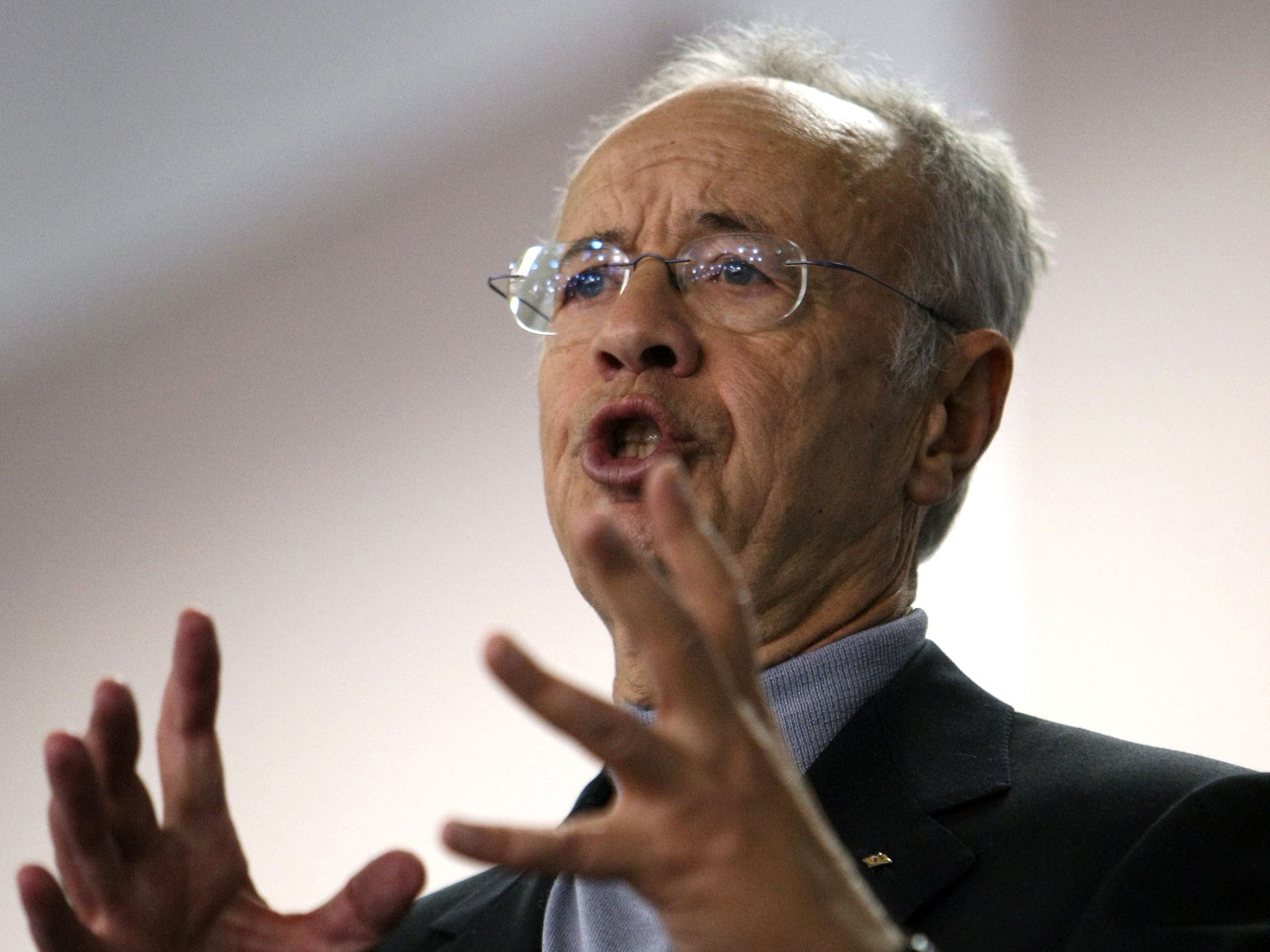

Your support makes all the difference.In September, Silicon Valley's Churchill Club honored former Intel CEO Andy Grove with its "legendary leader" award. The tech industry icon transformed Intel from a struggling memory chip maker into a microprocessor powerhouse. Grove has since devoted his substantial wealth and intellect to research on two diseases for which he's been diagnosed during his life—prostate cancer and Parkinson's.

After the videos and accolades were over, Grove stepped onto the stage and asked if he could say a few words. "Let's remember that millions of young people who had the misfortune of being born in the wrong national boundaries are going through all the horrors [that] I had to," Grove said. "I made it. Let's try in a little way to help them make it."

You see, Grove—one of America's most admired business leaders, up there with Bill Gates and Steve Jobs for the impact he had on the tech industry—was once a refugee. Born to a Jewish family in Hungary in 1936, he survived the Nazis only to flee Hungary after Soviet tanks rolled in to Budapest to crush the Hungarian Revolution of 1956.

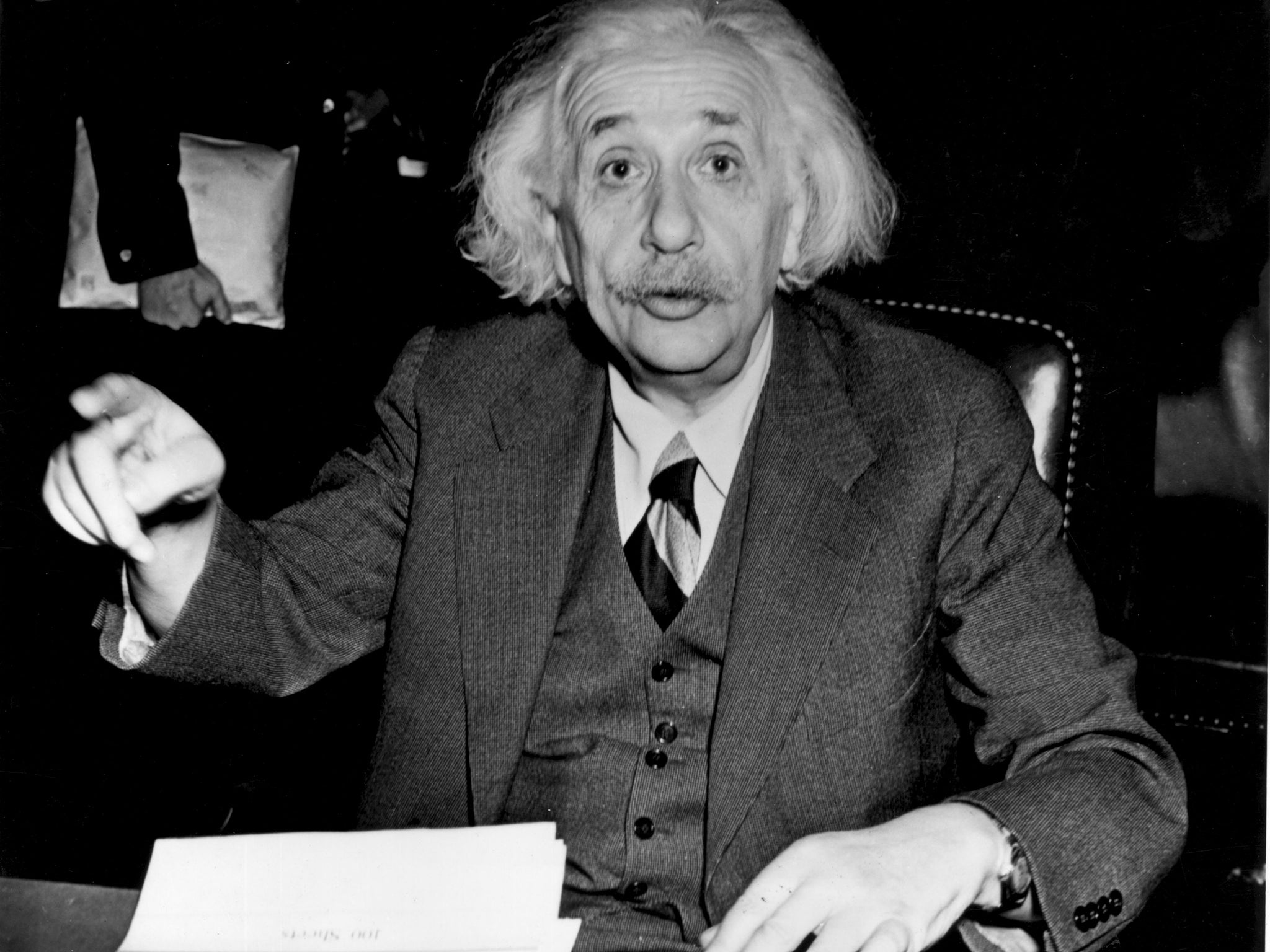

Grove is one of many people who have fled persecution, violence, war or political oppression to create something extraordinary out of their lives. Former U.S. Secretary of State Madeleine Albright and her family fled to America following the Communist coup in 1948. Albert Einstein was a German-Jewish refugee who escaped Nazi Germany in 1938.

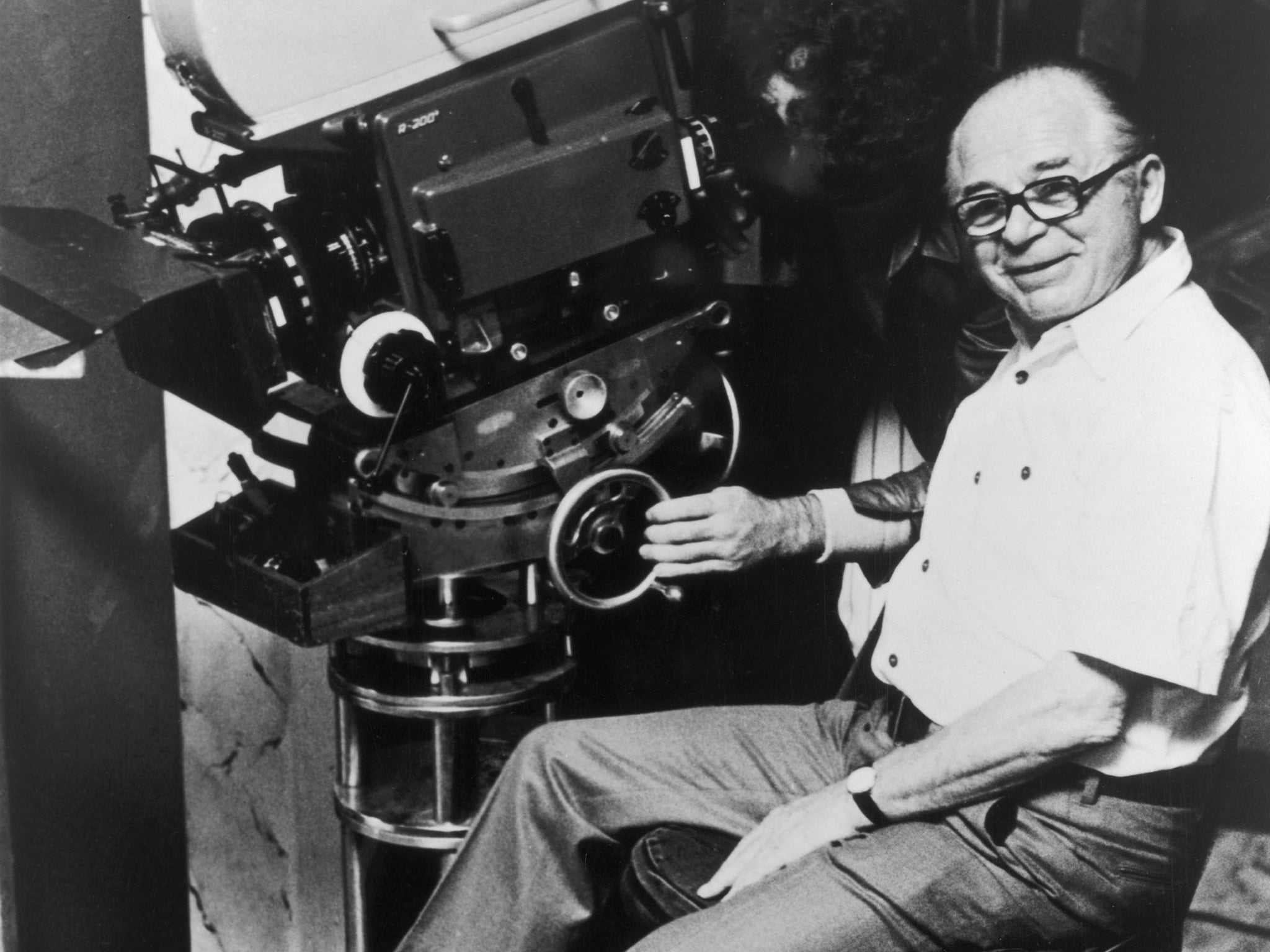

The film director Billy Wilder ("Sunset Boulevard," "Double Indemnity," "The Apartment") left Germany amid Hitler's rise and his mother, grandmother and stepfather were killed at Auschwitz. Thong Nguyen, whose family escaped Vietnam in 1975, is now a top executive at Bank of America.

The list goes on.

Such stories are a stark reminder of one thing that seems to have gotten lost amid all the negativity that current and would-be political leaders are slinging over Syrian refugees coming to the United States. Nearly all the focus has been on what the chances are that one of them could be a terrorist, rather than the possibility that many of them or their children could become notable leaders.

Never mind that, according to the Migration Policy Institute, just three of the 784,000 resettled refugees since 9/11 have been arrested connected with terrorist activities. (Two of those instances were not in America and "the plans of the third were barely credible," according to the institute's co-founder.) Or that the process of screening refugees in the United States is actually quite onerous, rigorous and lengthy. Or, among other things, that rejecting refugees could actually help ISIS.

On Thursday, the House passed a bill that would require intelligence, FBI and Department of Homeland Security leaders to certify that each refugee applicant is not a security threat. This followed moves by more than half the country’s governors to oppose letting Syrian refugees into their states—with New Jersey Governor Chris Christie going so far as to say even young orphans shouldn't be admitted under current vetting. Texas Governor Greg Abbott put it this way in a letter to President Obama: "Texas cannot participate in any program that will result in Syrian refugees - any one of whom could be connected to terrorism - being resettled in Texas."

Yet it's worth remembering that the inverse is also true: What if, in turning away Syrian refugees, we were to miss out on the ones who could change industries, upend scientific theory and create cultural masterpieces? What if we keep out the next Andy Grove? What if fear, ironically, causes us to reject someone whose leadership, courage and creativity could make the world a safer, better place?

What we're seeing right now is a pessimistic and reductive worldview for leaders, one driven by fear at the expense of possibility. Of course, it is critical for our country's leaders to worry about security, remain vigilant and weigh all the risks. But weighing those risks requires not just thinking about whom we might let in, but what remarkable individuals we might keep out.

© Washington Post

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments