Welcome to the hot chef renaissance. It’s complicated

Growing up in France, Clémence Michallon was not taught to think of chefs as objects of desire. An ongoing cultural moment begs to differ

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

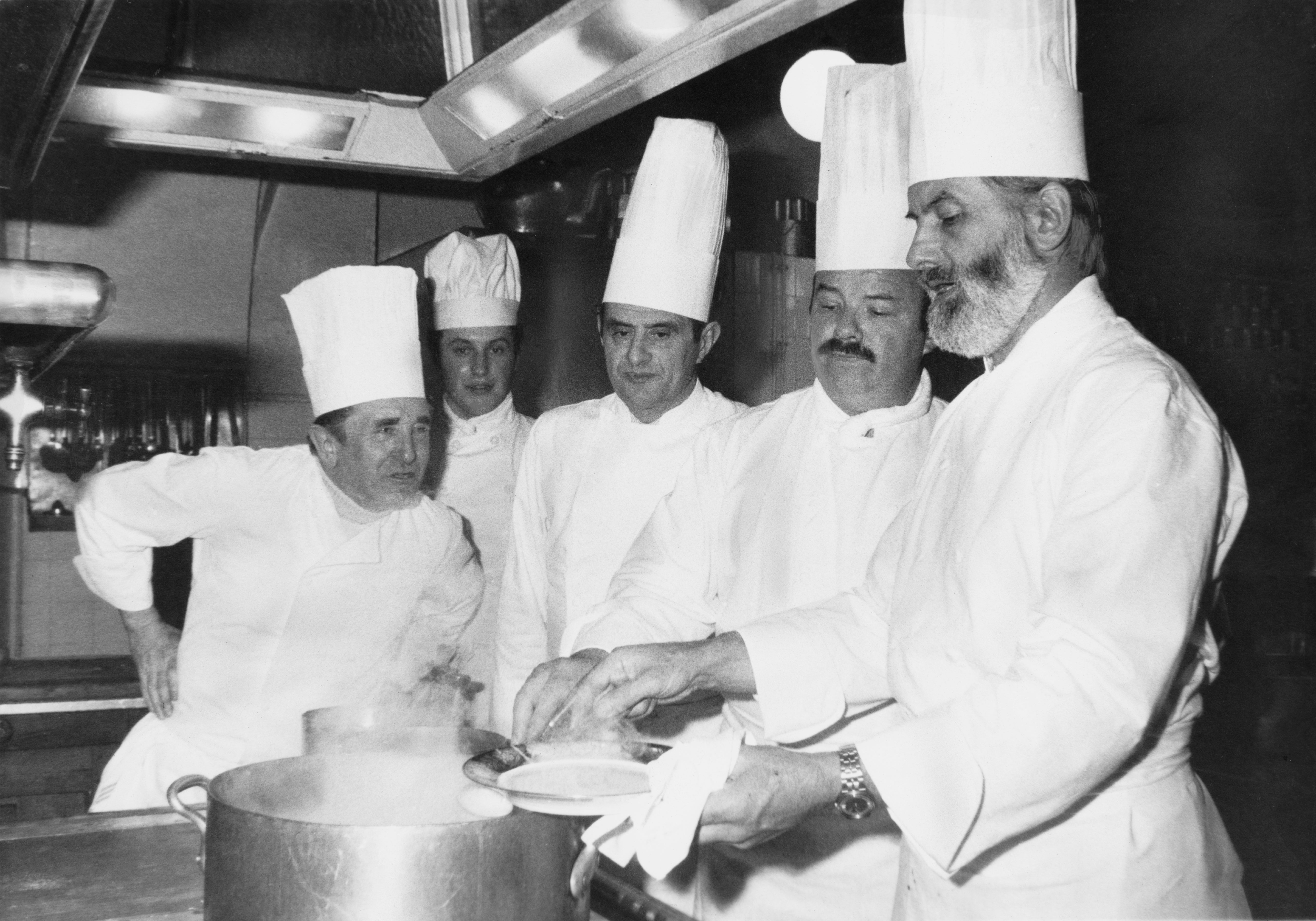

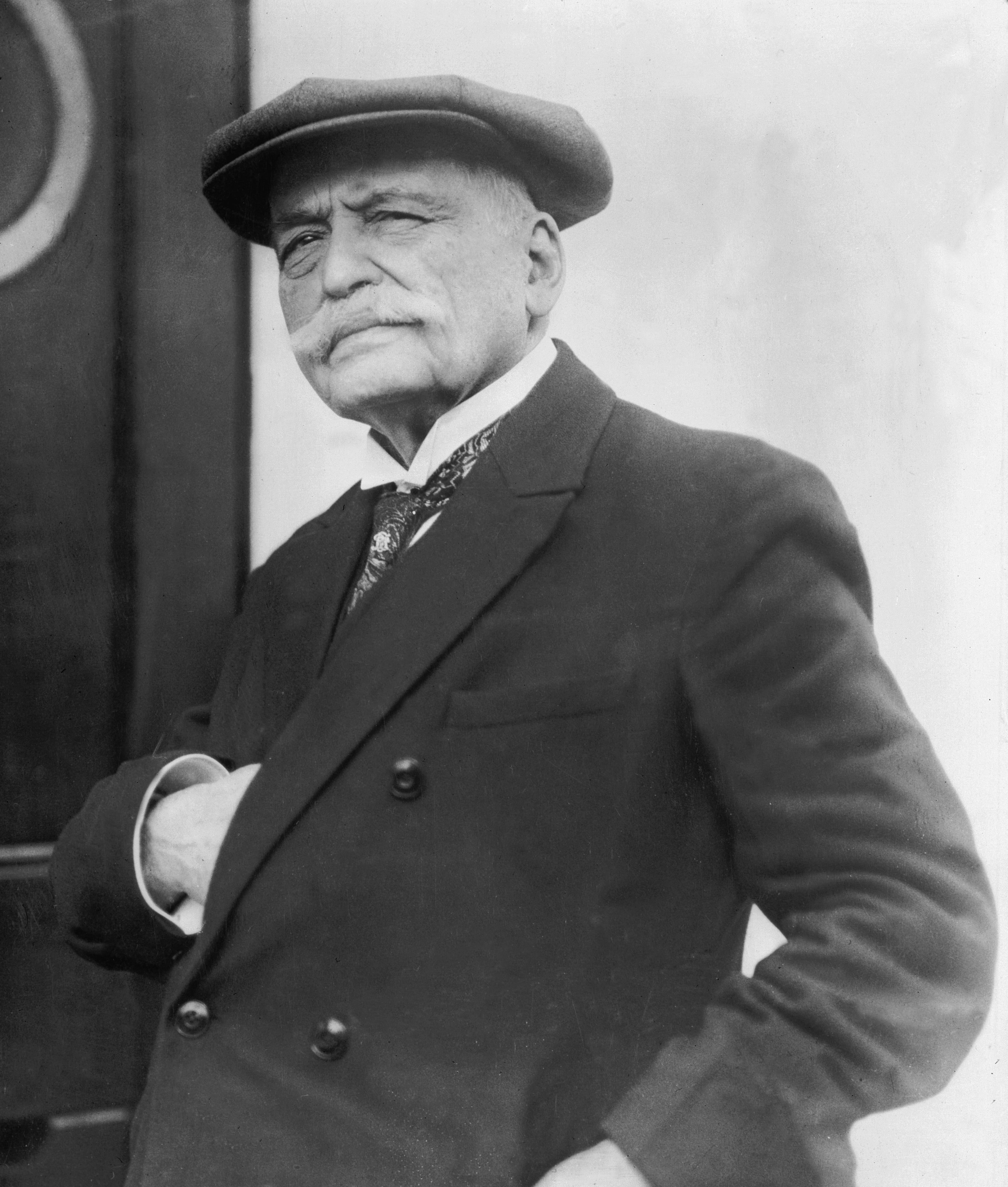

Your support makes all the difference.Growing up in France, I was taught that chefs were artists. They were to be respected. They were mysterious, remote figures, creating magic in the secrecy of their kitchens. A chef was a product of our culture. A chef was, usually, a man, at least middle-aged. A chef had Michelin stars. He likely had a belly (all those incredible dishes aren’t gonna taste themselves) and wore a tall, funny hat. A chef was Paul Bocuse. He was Alain Ducasse. He was Joël Robuchon. A chef was to be respected and feared, perhaps in equal measures.

What a chef was not: an object of desire. In 1990s France, it did not occur to us to lust after chefs. Certainly not with anything resembling the fervor earned by Carmen Berzatto, the oh-so-broken, oh-so-hot (and, crucially, oh-so-fictional) chef portrayed by Jeremy Allen White in The Bear, the surprise runaway success of the summer.

White’s performance (or Carmen’s characterisation, depending on how you choose to look at it) has launched a slew of takes. “Everyone’s Horny for the ‘Sexually Competent Dirtbag Line Cook,’” proclaimed a prescient Bon Appetit column. “The Bear’s Carmy Is Sexy As Hell, But Will He Change Diapers?” mused Romper.

This Hot Chef Summer (made all the more striking by the fact that White’s character in The Bear is seemingly uninterested in anything resembling romance; he does not have the time nor the bandwidth nor, frankly, the emotional maturity; besides, his kitchen is on fire and his hair soon will be too) looks likely to turn into a Compellingly Menacing Chef Fall. The Menu, a black comedy horror film with a haute cuisine theme, will be released in the US on 18 November. The details of the plot have been kept under wraps, but a trailer unveiled in August foretells a tale in which a chef de cuisine seems equally determined to feed and kill his guests.

How did we get here? How did we go from the French chefs of my youth to Jezebel (deservedly) erecting Jeremy Allen White’s hands to the status of Crush of the Week?

A friend suggested I start this piece with the sentence “Gordon Ramsay was evidence that America had daddy issues,” and I want to believe that she’s on to something. But Ramsay doesn’t feel like the beginning; he feels like the continuation of a movement that started long before he angrily (but appealingly) sharpened knives on network television.

It all began at a time when Ramsay was still becoming a classically trained chef and a fluent French speaker, who would earn 16 Michelin stars over the course of his career.

To chef Ed Szymanski, who opened Dame, a modern English restaurant, in New York City’s West Village with his partner Patricia Howard last year, the making of the modern chef began three decades ago. In 1990, the British chef Marco Pierre White published the cookbook-memoir hybrid White Heat. The book established him as “the original rock star chef,” as Anthony Bourdain himself put it in a cover blurb for White’s book – and paved the way for all the rock star chefs who have since followed.

Adorned with black and white photos of a young White (he was not yet 30 when the book was published), White Heat holds within its pages the key ingredients of the bad boy chef archetype we have come to know (and love, and hate, and deconstruct, and reconstruct) so well. There is passion. There is seriousness. And underneath it all, there is a certain wild-card-ness – something compelling but also slightly ominous.

White is seen on a 25th anniversary edition of White Heat wrapped in an apron, holding a large machete, seemingly yelling something in the direction of the camera. It’s a good cover image, but the real money shot is found inside: it’s a photo of a young White, all apron and rolled-up sleeves and grimy sneakers and wild hair, standing on top of a stove, bent in half, grabbing onto a pot. Why has he climbed onto the stove? We don’t know, but the intensity of the shot compels us to assume he has his reasons. This is what so many of us see when we look at a chef: someone who gets his hands dirty. Who does what needs to be done, even if it doesn’t immediately make sense, and doesn’t have time to explain.

Ten years after White Heat, Bourdain’s own book, Kitchen Confidential, cemented the public’s fascination with restaurant kitchens and those who run them. A New York Times Bestseller, and now an essential reference in the food memoir category, it’s a vivid, often rollicking read. In the kitchen, the cooks “were like gods”, Bourdain recalls.

“They dressed like pirates: chef’s coats with the arms slashed off, blue jeans, ragged and faded headbands, gore-covered aprons, gold hoop earrings, wrist cuffs, turquoise necklaces and chokers, rings of scrimshaw and ivory, tattoos – all the decorative detritus of the long-past Summer of Love.” The kitchen, in Bourdain’s book, is where a bride, “blonde and good-looking in her virginal wedding white”, might find herself at the end of her wedding dinner “bent obligingly over a fifty-five gallon drum, her gown hiked up over her hips” as Bobby, the restaurant’s chef, “noisily rear-[ends]” her.

Food tourism and food-centric TV shows contributed to shaping the modern chef mystique as we know it, Szymanski says. With such source material, it makes sense that the world of fiction would want to explore the kitchen too. On the big screen, there was the 2014 movie Chef, starring, directed, and written by Jon Favreau. The British film Boiling Point, released in November last year in the US, stars Stephen Graham as a chef who slowly falls apart during one ill-fated dinner service. It shares some similarities with The Bear: it was filmed in one shot, like episode seven of the series. It touches on themes like perfectionism, the pressures of running a restaurant, and addiction. In Boiling Point as in The Bear, the kitchen is a canvas for a chef’s personal issues and traumas, which boil over like milk out of a pot and burn more than one person in the process.

To someone who has never worked in a kitchen, the trope of the chef as we have come to conceive of it is at once fun and cathartic. But it needs the full remove of fiction in order for the charm to operate.

Szymanski did not fall under Carmen Berzatto’s charm after watching The Bear. The show, to him – someone who has worked in kitchens for a decade – depicts “abuse 101”.

“It’s a fictional TV show, but it’s based on a lot of real environments,” he says. “The culture that hyped up chefs to such an immense degree that they felt they were incredibly powerful and could do anything – that culture had a big split with the Me Too movement. And a lot of high–profile chefs who were seen through that lens, it turned out they were abusing their staff.”

In his own restaurant, Szymanski says he has tried to take steps to create a healthy environment; he and others make an effort not to raise their voices. The restaurant is closed on weekends, and employees work four days a week, not five – measures deemed by Eater “utterly radical” among New York City restaurants.

“You can make business decisions that maximise profit, or you can make business decisions that maximize staff happiness,” he says.

Going back to The Bear, Szymanski refers to the show’s seventh episode, famous among fans for being the one where six episodes’ worth of tension finally breaks. A mishap snowballs into a full disaster, and Carmen – red-cheeked, sweaty, crumply-faced – erupts at his staff. The episode consists in 20 minutes of yelling, swearing, and Sharpie-throwing. It’s gripping to watch.

To Szymanski, though, it’s a reminder of the real toxicity of his industry, and such behaviour proof that Carmen should be in therapy. “I don’t think I would be able to employ anyone who acted the way [Carmen] did,” he says.

The show itself appears to agree with Szymanski. (Spoiler alert for the rest of this paragraph.) Carmen seeks help, not in therapy, but in Al-Anon meetings, where he tries to process his brother’s death by suicide. His behaviour costs him his closest ally in the kitchen, his sous-chef Sydney Adamu (wonderfully portrayed by Ayo Edebiri). When he finally apologises to her, the writers make him spell it out: “My behaviour was not okay,” he writes Sydney in a text. Rewatch the season one finale, and you’ll see that in the end, it’s not until Carmen very literally calls out for help that things truly start to feel like they might get better for him and his restaurant.

Szymanski, who watched The Bear in its entirety, isn’t alone in his reticence. “I could barely get through The Bear,” former cook Genevieve Yam wrote in Bon Appetit, in a piece for which she spoke to other cooks and chefs who shared the sentiment. “Not because I thought it was bad television – but because it was the most accurate portrayal of life in a restaurant kitchen I’ve seen in a while.” The show, to her, “was so accurate that it was triggering.”

The series remains kind to Carmen. It needs to be: his trauma looms so large on the plot it becomes the center of this fictional universe, in a way that could and should never be replicated in real life. Speaking with Szymanski, I interrogate my own reaction to The Bear. Fiction, I believe, is where we take care of the weirder, more complicated parts of ourselves. At the same time, I have never worked in a kitchen, but I have encountered toxic men, and there is nothing layered, nothing even remotely complex about the contempt I feel for them.

I want to believe it wasn’t Carmen’s temper that I so enthusiastically responded to (I watched the show in two days, then immediately watched it again), but his other qualities. I aspired to his competence. I recognised myself in his moments of helplessness. I envied his gumption. I loved the way he told off a friend, in the pilot episode, who called Sydney “sweetheart” to her face – “Don’t say ‘sweetheart,’ you f*****g weirdo,” was Carmen’s immediate reaction. In this moment, there was something compelling in the no-nonsense anger of a fictional chef, warding off the weirdos of the world.

“My love for chaos, conspiracy and the dark side of human nature colors the behavior of my charges,” Bourdain wrote in Kitchen Confidential 22 years ago, “most of whom are already living near the fringes of acceptable conduct.” As I return to the French chefs of my youth, I realise this is the part of the picture I wasn’t seeing. This is what I and so many others have found in the figure of the chef as a trope, a theoretical being molded by works of fiction and reality shows: a conduit to make sense of our love for chaos, conspiracy, and the dark side of human nature. Bon appetit, or perhaps bonne chance.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments