Thanksgiving talk-line that helps people cook their turkey dinners still operating after 38 years

Experts receive more than 100,000 calls and messages each year

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.The internet should have killed the Butterball Turkey Talk-Line years ago, but all the Google searches, YouTube videos and turkey tweets in the world can’t match the small-bore magic that happens here on the fifth floor of a suburban office building 34 miles southwest of Chicago.

Each year from 1 November through Christmas Eve, 50 Butterball experts ease more than 100,000 nervous cooks through their Thanksgiving meal, either over the phone or, more recently, through text, email or live chat sessions.

The talk line started 38 years ago as a marketing gimmick and has grown into a seasonal slice of Americana as sturdy and reassuring as a Midwestern grandmother with a degree in home economics, which many of the experts are.

“People can be just paralysed with fear,” said Phyllis Kramer, who first took the seasonal job 17 years ago after retiring as a home economist. “All they usually need is someone who takes the time to be personal and sympathetic.”

Ms Kramer embraces the talk-line ethos, which requires a cheery, solution-oriented and non-judgemental demeanour. But who doesn’t love a good kitchen disaster story? It doesn’t take much to coax the experts into spilling some tea on America’s turkey illiteracy.

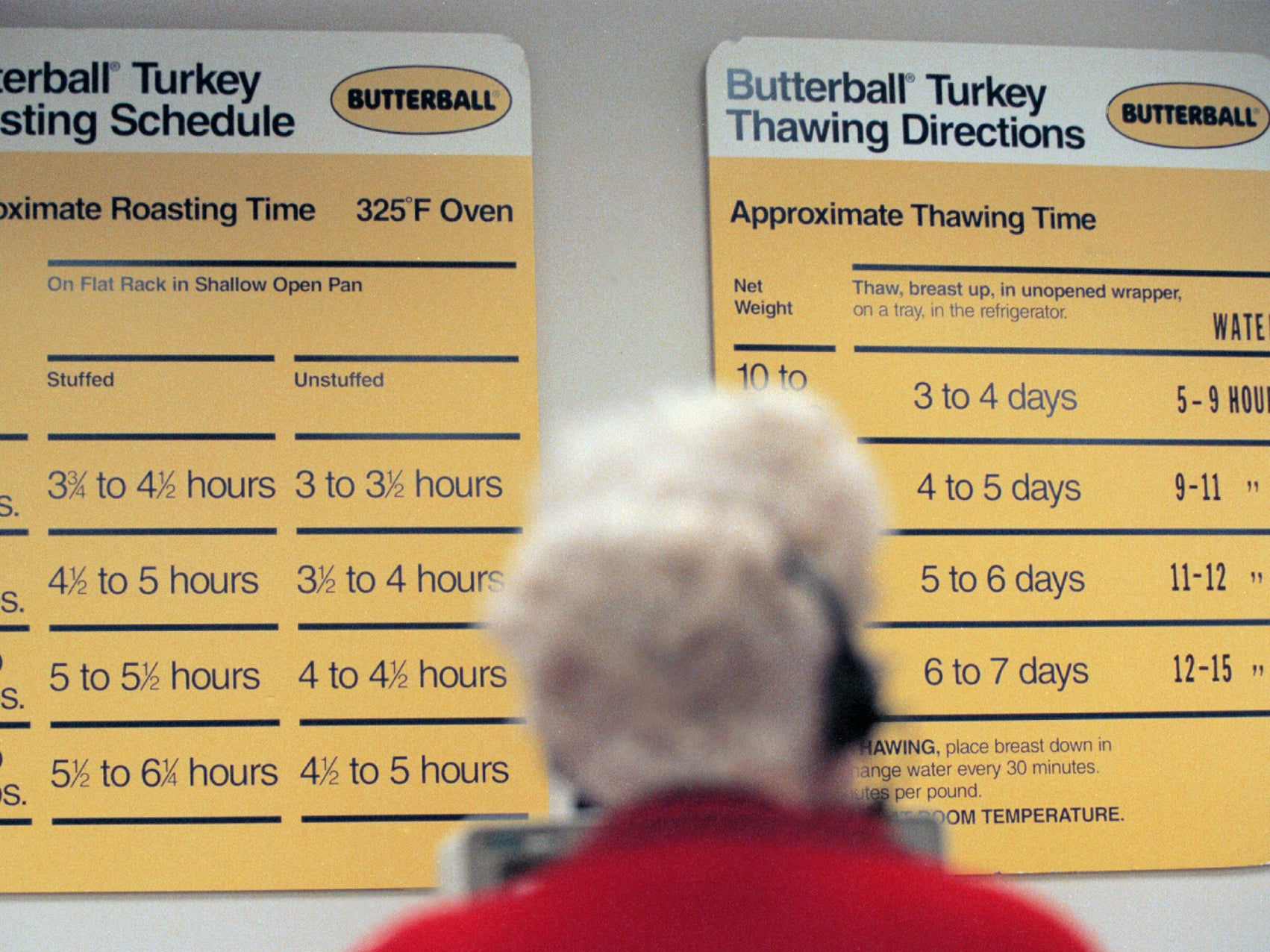

Their version of comedy gold often centres on thawing, the most common topic among callers. People ask if they can thaw a turkey in the dishwasher, under an electric blanket or in the backyard pool. One man threw a wrapped turkey in the bath water with his two children.

Here’s a classic: A man called in, worried about whether his bird would thaw in time. “What state is your turkey in?” the expert asked, trying to do a little culinary detective work. “Florida,” he answered.

Then there was the woman who wanted to know if she could check the turkey temperature with a fever thermometer, another who used dish soap to wash the turkey and the newlywed who called from a closet, fearful that her mother-in-law would discover she didn’t know how to roast a turkey.

Ms Kramer’s favourite call came five years ago, when a group she suspects was fuelled by a few holiday cocktails complained that the 21-pound turkey they had just pulled from the oven had barely any meat. She was puzzled but then had a moment of what she called divine inspiration. “Turn the turkey over,” she suggested. They had cooked it breast-side down.

“The internet isn’t going to tell them that,” Kramer said.

The Butterball talk line is one of the great marketing ideas of modern American consumerism, right up there with using a national baking contest to promote Pillsbury flour or Clydesdales to sell Budweiser.

It was born in 1981, when Pam Talbot, an executive of the Chicago public relations firm founded by feisty former journalist Daniel J. Edelman, pitched the idea as a way to help deal with what she tagged “turkey trauma”.

The first year, six women fielded 11,000 calls on a toll-free line — no small thing in an age before unlimited calling plans and mobile phones. Their reference material was contained in small binders.

Today, the experts, all of whom possess some kind of culinary or nutritional background, have an elaborate database of turkey tips and recipes at their fingertips, with links at the ready to send out via text and social media. Last year, Butterball loaded answers spoken in the experts’ voices into Amazon’s Alexa voice assistant.

They do their best to keep up with the trends. Last year, there were a lot of questions about Instant Pots and sous vide. This year, spatchcocking and air frying are popular. And always, there are questions about deep-frying.

Still, the people in headsets remain steadfast in the belief that the company’s preferred method is best: Coat the turkey with oil or cooking spray. Use a shallow roasting pan with a rack, a bed of aromatic vegetables or, in a pinch, a coil of foil. Cook at 160 degrees. A 10- to 18-pound turkey will take three to 3 1/2 hours if you don’t open the oven to baste it, which isn’t necessary anyway. The thigh should reach 82 degrees and the breast 76 degrees, which you achieve by placing a foil tent over the breast in the last half-hour.

The Edelman company still helps coordinate the talk line, which has so embedded itself in popular culture that it’s name-checked regularly on talk shows and once worked its way into the fictional Oval Office on The West Wing.

“It’s the most brilliant piece of branding,” said Joanna Saltz, editorial director of Delish and House Beautiful. “In the day and age of automated everything, getting a live human on the phone on the most culinary challenging day of the year? It’s so genius. It’s like calling the police.”

Evan Kleiman, the former Los Angeles restaurateur who answers Thanksgiving questions during her prerecorded radio show, “Good Food,” is a steadfast fan. “It’s some woman talking you off the ledge,” she said. “Don’t you wish there was one for everything else?”

The call traffic starts picking up in earnest the Thursday before Thanksgiving, which Butterball calls National Thaw Day. Go time is Thanksgiving itself. The action starts as soon as the line opens at 6am and doesn’t stop until it closes 12 hours later.

To keep their voices from going hoarse on Thanksgiving Day, the experts rely on soup, mints and plenty of water. They’ll field more than 10,000 calls. (That’s a mere drop in the gravy boat compared with the estimated 40 million turkeys that will be cooked on Thanksgiving.)

The concept is so enduring that competitors like Jennie-O Turkey Store and food media organisations have adopted it. The Splendid Table host Francis Lam will preside over a panel of cooks including New York Times columnist Melissa Clark, who will take calls live for few hours on Thanksgiving Day.

The Butterball help-line office, with a doorbell that gobbles and an inflatable roast turkey, is not a place where culinary envelopes are pushed or global perspectives are embraced. Culturally, the talk line is as white as a turkey breast. The help it offers — based on hundreds of tests on Butterball products — is safe, reliable and seasoned with not much more than salt and pepper.

That’s what callers are usually looking for. At least it was for Jee Won Park, a New York publicist who called the Butterball line in 1997, when she was in her early twenties.

A friend in New Jersey had bought and stuffed a big turkey, and she headed over to help him cook it. After about four hours, a little red plastic button inserted into the breast as a guide to indicate doneness had failed to pop up. Was it done?

Ms Park didn’t know anything about roasting turkeys because her Korean-born parents never did it. A call to his friend’s mother, who had immigrated from China, was equally fruitless.

In those days, internet searches were still cumbersome. There was no other option than to call Butterball.

“It gave us some agency,” she said. The woman on the other end of the line was wonderful but ultimately couldn’t help the desperate cooks because they didn’t know how much the turkey weighed nor did they have a meat thermometer. They ended up roasting it for about six hours, and it was awful.

“It didn’t feel like a gimmick, and that’s the beauty of it still,” Ms Park said. “In some ways it’s a selfless kind of thing. I know they benefit, but it doesn’t feel gross to me.”

Of course, the talk line is ultimately about selling turkeys. And data gathered from the callers helps Butterball’s marketing strategy. But why be so cynical on Thanksgiving? There’s a lot of heart here underneath the corporate logos that hang on the walls.

Many of the experts have developed long-standing friendships. They have worked together for decades, watching babies grow up and mourning the passing of family members.

It’s the kind of bond that can be formed only when the calls are stacking up like dirty dinner plates and a cook’s emotional state on the nation’s premier food holiday is precarious.

Only a fellow Butterballer knows how difficult it is to not launch into a lecture about oven calibration when an angry caller blames you because a turkey took five hours instead of three to cook.

Who else understands what it was like during the talk line’s early #MeToo moments when men would call to ask if the women made “house calls”? One particular creep, emboldened by a very homey Ladies of the Talk-Line calendar in 2002, called to ask an expert’s breast size.

Last year, they had to contend with a flood of calls from anxious parents who had been trolled as part of the viral turkey challenge, in which their children sent them texts asking how long to microwave a frozen 25-pound turkey, and then posted the befuddled responses online.

Almost all of the experts have that one deeply meaningful call. It came for Bill Nolan in 2016. He’s a chef and retired culinary educator whose other job involves preparing meals for a group of priests. He is relatively new — one of only a few men on the talk line, which didn’t hire its first until 2013.

Mr Nolan picked up a call from a widowed man the day before Thanksgiving. “He said his wife was gone, but he wanted to make that first Thanksgiving meal without her for his family,” Nolan said.

Tears came to his eyes as he told the rest of the story. Although the average call is about three minutes, he spent almost a half-hour with the man, coaching him through a simple Thanksgiving meal.

“I mean, here was this guy in a house by himself who called us to help,” Mr Nolan said. “We don’t cure cancer, and we don’t save lives, but maybe that guy had a good meal.”

The New York Times

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments