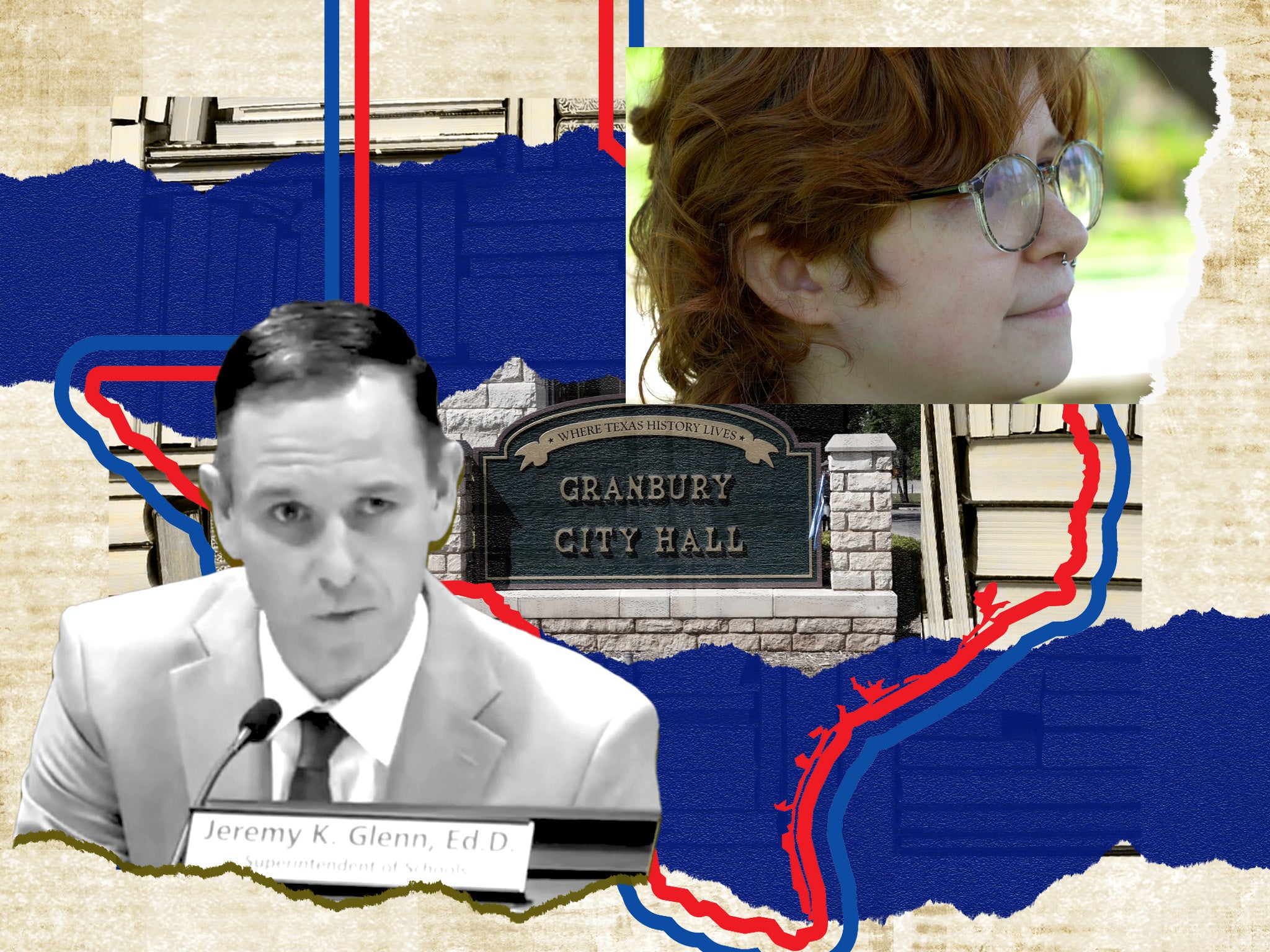

‘They were trying to erase us’: Inside a Texas town’s chilling effort to ban LGBT+ books

This Texas town tried to impose one of the most severe book bans in the country. LGBT+ students fought back. Richard Hall reports from Granbury, Texas

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Lou Whiting remembers the day local officials came to their school library in the quaint Texas town of Granbury and started carrying away boxes of books.

“The fact that they did it during the school day is what really shocks me, because that’s blatant, that’s right in your face,” Whiting, who identifies as non-binary and is a senior at Granbury High School, tells The Independent.

That moment was the culmination of one of the most sweeping book-ban efforts made by any school district in the entire United States. Despite fierce opposition from students, Republican school board officials moved ahead with a months-long effort to remove hundreds of books they deemed inappropriate for schools.

These were not just any books; the vast majority were targeted because they contained LGBT+ themes. There were stories about gender, sexuality and race. Members of communities represented in those books began to feel like they were under attack.

The incident caused a rupture in this town, and far beyond. It led students and parents to protest, caused rowdy school-board meetings, tore families apart, and even brought to the district a first-of-its-kind civil rights investigation by the Department of Education.

The banned book list

Granbury’s book-banning frenzy came at a time when similar efforts were sweeping the country. Last year saw a record high of more than 1,200 attempts to remove books from schools and libraries, according to the American Library Association.

Those bans, pursued by Republican lawmakers in numerous states, were ostensibly to protect children from harmful material. But just like in Granbury, the vast majority of the books they were trying to ban were restricted to a few familiar themes: PEN America described the measures as part of a “concerted campaign” taking place across the country to ban books with content that amounts to “little more than an acknowledgment of LGBTQ+ identities or the existence of racism or sexism”. Most of these campaigns were fuelled by right-wing activists with an anti-LGBT+ agenda.

The town of Granbury, which has a population of just over 11,000 and was named after a Confederate general, attracts tourists from across America, who come to see its historic downtown buildings. It has won the award for “Best Historic Small Town in America” twice for its efforts to preserve that history. The county in which it lies voted for Donald Trump by 81 per cent in the 2020 presidential election. It counts among its residents Stewart Rhodes, leader of the anti-government Oath Keepers militia, who was found guilty of seditious conspiracy for his role in the attack on the US Capitol on 6 January 2021.

When the book bans came to Granbury, they came at a speed and scale unseen elsewhere. One day, in October 2021, a Texas state representative called Matt Krause sent a list of more than 850 books to school districts across the state, asking them to identify which titles on the list were held in their libraries. According to an analysis by Book Riot, the list overwhelmingly targeted books about LGBT+ issues. Krause’s letter asked school districts to identify books in their possession containing material “that might make students feel discomfort, guilt, anguish, or any other form of psychological distress because of their race or sex”.

Most districts ignored the list, but the town of Granbury used it as a guide. In January 2022, Granbury’s school district began removing books included in Krause’s list from library shelves for “review”. It did so without public consultation and without revealing which books were being removed.

In a statement explaining its decision, the school district said: “While we acknowledge some parents and community members will not agree with the potential removal of any book, we understand the conservative climate of our community and that a large majority recognises that several social and cultural topics are best left to parents and families to discuss with their children.”

Whiting, who was a junior at the time, saw the bans as an attack on the entire LGBT+ community. For them, it wasn’t just about books, but about their very existence.

“They were trying to erase us,” Whiting tells The Independent. “The first step ever taken throughout history when it comes to genocide is lack of representation. You take away what they can give to other communities, you take away the literature, you take away art, you take away representation of culture, and then it moves on to the next step, and the next one and the next one.”

Students and teachers opposed to the bans did not know precisely which books were being removed, but they knew they were coming from Krause’s list. That was enough to move them to act.

At a contentious Granbury school board meeting on 24 January 2022 – one of many to shake the town throughout the year – students and parents spoke out against the impending bans.

Christopher Tackett, a parent of a Granbury High School senior and a former school board trustee himself, was among those who objected to the bans. He tells The Independent that the bans were the work of a small group of committed activists whose aim was to introduce more religion into schools.

“It is part of a larger movement to take the levers of power on school boards, city councils, county commissioners... to be able to impose a very specific ideology into that. And in most cases, it’s connected to religion – the term that is used broadly is Christian nationalism,” he says.

“It truly is abusing the power you’ve been given by your communities in local elections. Turnout’s not really high. The people who feel passionately about injecting religion into schools, they show up to vote,” he explains. “It creates this imbalance of the reality, of a way a community really feels about these things. And you’ve got this small, very vocal minority with a certain ideology and a certain agenda imposing that agenda upon an entire school district, upon an entire community.”

At the January meeting, the school board voted 7-0 to change the rules to allow them to “remove materials because they are pervasively vulgar, or based solely upon the educational suitability of the resource in question”.

The district pushed ahead and removed some 125 books from school libraries for review – all of them from Krause’s list. One student – Whiting’s friend – posted a picture of the local officials taking away the books in boxes marked “Krause’s list”.

The school board members advocating for the bans insisted they only had the best interests of students in mind. At the 24 January meeting, the school district’s superintendent, Jeremy Glenn, called the opponents of the bans “gaslighters” and “radicals”, and said the books he had removed were “vulgar, the variety were sexually explicit and in my opinion pornographic”.

It wasn’t until two months later that a secret recording of Dr Glenn revealed an entirely different motivation for pursuing the bans.

‘Let’s just call it what it is’

In March 2022, a recording of a meeting between Dr Glenn and a group of librarians he had summoned would turn this local story into a national one, and prompt an investigation by the Department of Education.

At that meeting, which took place on 10 January 2022, Dr Glenn gave an unfiltered speech about what was really behind the effort.

“Let’s just call it what it is. I’m cutting to the chase on a lot of this. It’s the transgender, LGBTQ, and the sex, sexuality in books,” he said, according to the leaked recording.

“And I’m going to take it a step further with you,” he said, according to the recording. “There are two genders. There’s male, and there’s female. And I acknowledge that there are men that think they’re women. And there are women that think they’re men. And again, I don’t have any issues with what people want to believe, but there’s no place for it in our libraries.”

He went on to say that Granbury “is a very very conservative community. And our board is very conservative,” and that “if it is not what you believe, you better hide it. Because it ain’t changing in Granbury.”

That recording confirmed to many in Granbury what they had suspected all along: that the bans were less about protecting students than they were about targeting a particular community.

The recording formed the basis of a civil rights complaint by the American Civil Liberties Union against the Granbury school district in July 2022, which argued that the comments violated Title IX, a federal law that protects students from being discriminated against based on gender or sexual orientation.

Chloe Kempf, an attorney at the ACLU of Texas, says those comments were what led to the organisation’s direct intervention in the case.

“As soon as we heard those comments, we became very concerned, because it’s part of a broader trend that we were seeing across Texas of removing books that are specifically targeted at LGBT+ identities,” she tells The Independent. “This was a very clear example of somebody articulating the discriminatory intent behind the book removals.”

The complaint alleged that the district, through its superintendent’s comments and also the book removals, had created a “pervasively hostile atmosphere” for LGBT+ students, thereby violating federal law.

“Essentially, the theory is that when LGBT+ students hear the top person in their district making these disparaging comments, and they see books that reflect themselves being censored as inappropriate and shameful, it sends them a very powerful message that they are not welcome in the district, and that their identities should be hidden,” Kempf says.

In December 2022, the Department of Education’s civil rights division announced that it was investigating Granbury school district under Title IX. Legal experts told ProPublica that it was the first such investigation tied explicitly to the nationwide campaign to ban books that address LGBT+ themes.

That investigation is still ongoing, but Kempf says the problem is much bigger than Granbury.

“Politicians in Texas at every level are essentially trying to legislate LGBTQ people out of existence, be it through censoring books about them, restricting their access to healthcare, restricting their access to playing sports, and even expressing ourselves through art and what we wear. And so I think it’s a very worrying time,” she says.

The Independent contacted every member of Granbury’s school board to request comment, but none replied.

‘That’s my mom’

The book bans in Granbury didn’t just divide a town, but families, too. Here, and across the country, the bans appeared to be fuelled by the idea that removing certain books from circulation would stop young people from being gay. The idea that “exposure” to LGBT+ stories would somehow convert impressionable young children to a different lifestyle, rather than help them discover who they are, was pervasive.

It is an idea that Weston Brown heard frequently growing up in a strict Christian household in Texas. When he came out to his family, after many difficult years of being denied access to any kind of book about sexuality or even biology throughout his homeschooling, his family excommunicated him.

Years later, he was scrolling Twitter when he saw a video of his mother, Monica Brown, trying to impose the same kind of censorship on other kids. The video showed her at a Granbury school district meeting, calling for pastors to decide which books children should read, and for punishment for librarians who stocked books she deemed unsuitable.

“This is my mom. I’m shaking,” he wrote in reply to the person who had posted the video.

When he saw his mother pushing for the same kind of censorship for other children that he had faced in her home as a child, he was moved to act.

“Previously I really didn’t have a great deal of interest in telling my story. It’s one that’s been told so many times before,” he tells The Independent, “but seeing my mom speak out like this and bring it to a public space, I thought, I have a stake in maybe breaking through to some of the folks who are listening to my parents.”

Weston, who was living in San Diego by now and had minimal contact with his parents, travelled to Granbury to speak at the same school board meeting where his mother had called for book bans. He didn’t know at the time that his mother would be in the audience that day, too.

“Today I strive to be the person I needed when I was young, someone who would stand up, speak out and protect the kid that felt alone,” he told the meeting, as his mother watched.

“I knew I didn’t fit the blueprint for the life that my parents were grooming me for. I wanted so badly to know that someone like me could find peace, happiness and love. I would have given anything to read a book [with a] character that felt the feelings I felt, to ask the questions I couldn’t ask, and learn the lessons that I needed to learn,” he went on. “I’m here today to implore you to listen to librarians, educators, and students, not those speaking from a religious perspective or at the bidding of a political group.”

Weston’s story was important to Granbury’s book-banning efforts because it seemed to directly contradict the very aim behind them: his mother had strictly prohibited any books about sexuality in an effort to make him into a person in her own image. None of it worked.

“They’re victims, in a way, to a significant amount of misinformation,” Weston says of his parents. “They grew up under a lot of anti-queer propaganda. And they were in a small town that was poorly funded, poorly educated. So they weren’t being exposed to these stories. I picture them as young children, and I imagine that they were just curious and exploring the world, and the people that were charged to take care of them, and raise them, and educate them, failed significantly.”

Monica Brown did not respond to The Independent’s request for an interview.

‘Hostile to queer people’

After community backlash, the Granbury school board eventually returned most of the books they had removed for review to the library. Of the 125 books pulled, three were banned initially and 122 were returned. Later, those returned books started to quietly disappear from the shelves, according to Christopher Tackett, the former school board member who tracked the library stocks via freedom of information requests. But the scars left by the battle over the books still remain, and the Department of Education’s investigation into the school district’s bans is still ongoing.

The bans brought the town’s LGBT+ community together in the fightback, and showed them that they were not alone. As a result of the bans, students formed a Gay-Straight Alliance club to foster solidarity and community. It also left some of them questioning their place in their hometown.

“I want to say I love living here in physicality, but living here as an individual who is queer, it’s not exactly the friendliest,” Whiting says. “In fact, if anything, I would say this community is quite hostile towards queer people.”

“This was censorship,” they add, “basically Granbury saying we don’t want you guys in our schools, just like we don’t want you in our libraries.”

Even after everything that happened, Whiting says, the book-banners have still not come to terms with the possibility that the central justification of their whole effort is fatally flawed.

“If a person is queer but doesn’t understand that yet, and reads a book about being queer... if anything, that will help them understand who they are. It’s not going to turn them into this whole new person,” Whiting says.

“It’s going to turn them into themselves, who they haven’t been able to understand they are. That’s growth.”

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

9Comments