Why Stephen King turned on his own publisher in a battle over the future of the book industry

Josh Marcus looks into why the horror king — and the Biden administration — has been trying to stop the big-money merger between Penguin Random House and Simon & Schuster

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.It didn’t involve any killer clowns, haunted hotels, or avenging, telekinetic high schoolers, but this summer, author Stephen King began telling a new scary story: the precarious state of the US book industry in 2022.

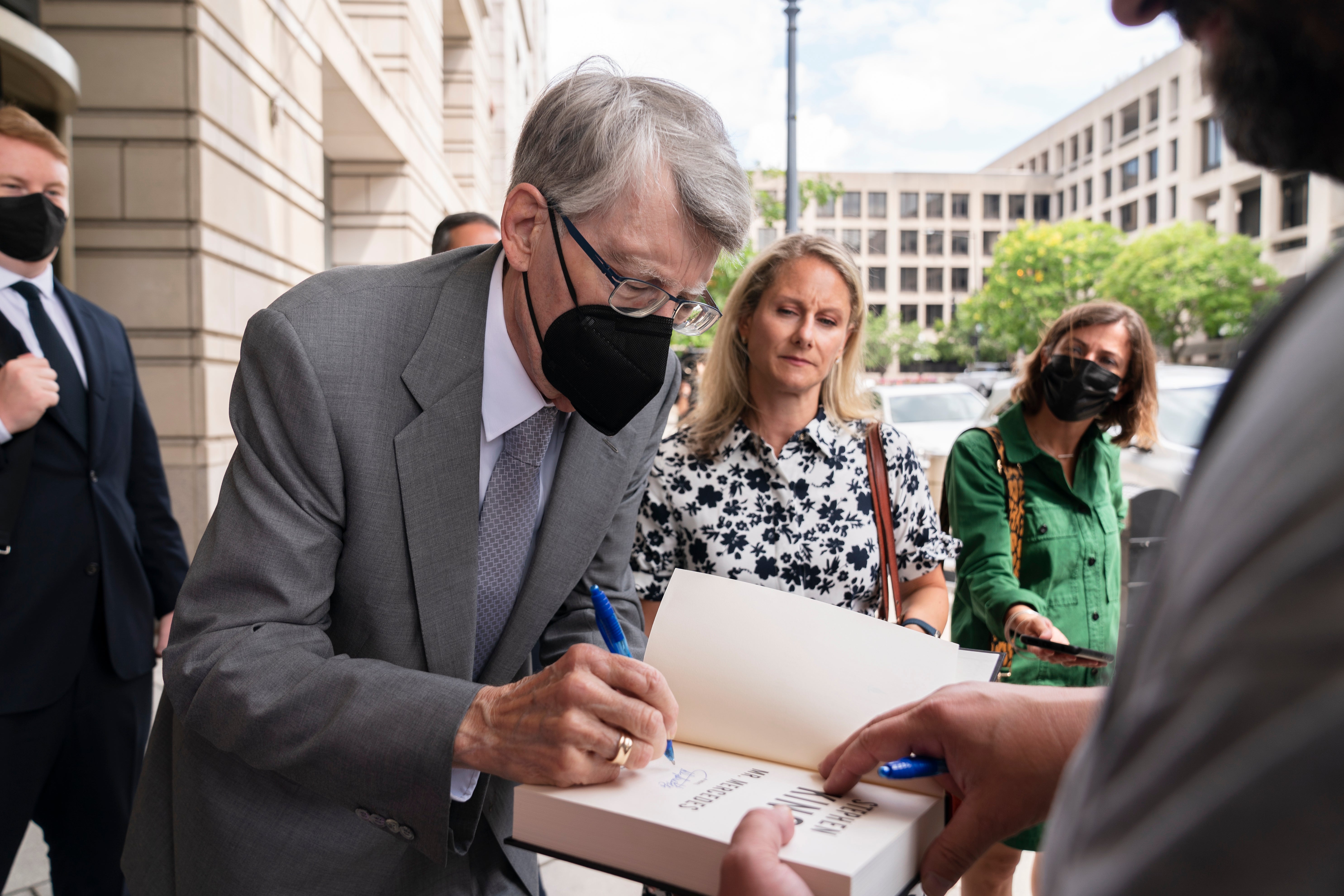

The author, who has written numerous horror bestsellers since the 1970s like The Shining and Carrie, testfied in August on behalf of the Biden administration in the Department of Justice’s effort to stop the proposed $2.2bn merger of Penguin Random House, America’s largest publisher, and Simon & Schuster, another of the “Big Five” companies that dominate the US book industry.

On 31 October a federal judge blocked the sale, saying the merger of the two companies could “substantially” harm competition in the US book market.

In November of last year, the federal government sued to stop the deal, arguing the tie-up would give the companies “unprecedented control” over who gets their voices heard in American cultural life, a development that “would result in substantial harm to authors”.

Over the course of three weeks of arguments in August, the trial dug down into the opaque world of big-money author advances and industry consolidation, exposing deep disagreements about how the deal would impact the book business, and by consequence, what the future of America’s literary culture looked like for writers and readers alike. The unprecedented case has been dubbed the publishing trial of the century.

For his part, Mr King, one of the most successful and well-paid writers of his generation, was willing to testify against his own regular publisher, Scribner, part of Simon & Schuster, to argue against more consolidation in the book industry.

"My name is Stephen King. I’m a freelance writer," he began cheekily, before railing against market conditions that have pushed many writers “below the poverty line”.

“I came because I think that consolidation is bad for competition,” he testified. “It becomes tougher and tougher for writers to find money to live on.”

“It’s a tough world out there now. That’s why I came,” he added. “There comes a point where, if you are fortunate, you can stop following your bank account and start following your heart.”

The clash with Mr King is one of many twists in the trial.

Though the case hinged on technical issues like the dynamics of author contracts, the definition of monopoly power, and the merits of various supply chain arrangements, everyone in the book world has been watching.

Readers might want to pay attention, too. The case not only impacts how people consume books, and at what price. Like any good story, this one also has plenty of drama and gossip to go around.

“This is a huge deal,” Michael Cader, founder of the Publishers Lunch newsletter, told The Independent before the judge’s ruling. “The trial was probably attended by a few dozen people, but was riveting to the entire industry. Both the potential consequences of the deal itself as well as simply the theatre of having peers and people in your industry on the stand discussing business details in granular fashion for three weeks was pretty compelling for a lot of people.”

The main argument in the case revolved around the big whales of the publishing industry, books where authors earned more than $250,000 on their advances for titles expected to top bestseller lists.

The DOJ claimed that a potential Penguin Random House - Simon & Schuster juggernaut would control half the market of such blockbuster books in the US.

“They are the only firms with the capital, reputations, editorial capacity, marketing, publicity, sales, and distribution resources to regularly acquire anticipated top-selling books,” DOJ lawyers said in a court filing.

The merger hopefuls, meanwhile, told the court in Washington, DC, that readers and writers had nothing to fear if the government allowed the Big Five to become the Big Four.

“It’s a good deal for all involved, including authors,” Stephen Fishbein, an attorney for Simon & Schuster, said in his closing statement.

Top leaders at Penguin Random House and Simon & Schuster said the book market was far more expansive and competitive than the slice the government was choosing to focus on, which covers about 1,200 books a year, or two per cent of the US commercial market, the companies argued in a pretrial brief.

Overall, in 2021, about half of the books sold in the US came from publishers outside the Big Five, Penguin Random House CEO Markus Dohle testified. The company also noted it had actually lost market share since the 2013 merger between Penguin and Random House.

More than that, the companies argued the process of acquiring books was a mix of expertise and gambling, where even publishing giants can’t guarantee a big-money purchase will translate to big sales and massive cultural reach, or predict when an upstart author’s book will become a breakout hit.

“These are not widgets we’re producing,” Madeline McIntosh, chief executive of Penguin Random House, said in testimony. “The evaluation is a highly subjective process.”

Claiming to predict a book’s bestselling future was like “taking credit for the weather,” added Simon & Schuster CEO Jonathan Karp.

This unpredictable process would remain de-centralised even after the merger, the companies went on, because Simon & Schuster and Penguin Random House editors would still be allowed to bid against each other for future titles.

Even to a fantasy author, however, this premise struck Stephen King as a bit out-there.

“You might as well say you are going to have a husband and wife bidding against each other for a house,” the writer testified. “It’s a little bit ridiculous.”

Amy Thomas, owner of Pegasus Books, which has stores in Solano, Berkeley, and Oakland, California, said the consolidation might also have cancelled out who gets published in the first place, leading to a potential diminishment in which new and important voices get heard.

The most important books aren’t necessarily ones that start out as instant profit-makers, but mergers often invite searches for quick places to cut costs. What’s more, she said, salespeople representing the massive combined catalogues of a merged Simon & Schuster and Penguin Random House might not have the time to champion all of their titles the way a smaller publishing house would.

“Things will get dropped. Lines will get dropped. There’s just too much,” she told The Independent. “There’s a lot of books. Not all of them work. And a lot of them are worth it anyway.”

Bigger companies may also have less incentive or ability to offer booksellers good terms, given the gargantuan scale of the proposed company’s operations.

Beyond the more technical questions about how a Simon & Schuster - Penguin Random House deal would affect author payouts and bookstores, there was also the slightly dishier matter of which authors got paid the big bucks and why.

On this question, the trial became a kind of literary Page Six, with mentions of Big Five publisher Hachette’s list of “the ones that got away”, and reported seven-figure paychecks for figures like actor Jamie Foxx and New Yorker magazine writer Jiayang Fan.

The publisher of Simon & Schuster imprint Gallery even testified that they paid “millions” for a book by comedian Amy Schumer, even though sales estimates suggested the book might not merit such a whopping payout.

The case also described how the collective $65m advance Barack and Michelle Obama got for their books neared a $75m threshold where Penguin Random House editors would’ve needed permission from their corporate parent, Germany’s Bertelsmann, to move ahead.

But the focus on these marquee names was more than just publishing industry gossip. The trial shone a spotlight on just how much a tiny proportion of hit books prop up the rest of the publishing industry.

Penguin Random House executives said that just over a third of their books turn a profit, with just four per cent of books in that category accounting for 60 per cent of the earnings. In 2021, according to data from BookScan, fewer than one per cent of the 3.2 million titles it tracked sold over 5,000 copies.

Given this state of affairs, the big publishers argued their merger would create corporate efficiencies, allowing them to pass these savings on so more authors got a bigger piece of the pie.

However, Judge Florence Y Pan seemed to strike down this line of thinking, refusing to admit Penguin Random House’s evidence to support this claim, arguing it wasn’t independently verified.

“The judge thoroughly and completely rejected the defence’s argument for accepting that evidence,” Mr Cader, of Publishers Lunch, said.

So did Stephen King.

“There were literally hundreds of imprints and some of them were run by people who had extremely idiosyncratic tastes,” he said. “Those businesses, one by one, were either subsumed by other publishers or they went out of business.”

His own publishing history tells the story of an industry increasingly controlled by a few companies. Carrie was published by Doubleday, which eventually merged with Knopf, which is now part of Penguin Random House. Viking Press, which put out other King titles, was a part of Penguin, which became Penguin Random House in 2013.

David Enyeart, the manager of St Paul, Minnesota’s independent Next Chapter Booksellers, says the industry’s long march towards consolidation makes it harder for new voices to emerge and reach readers in stores because smaller publishers simply can’t compete.

“They’re able to make more independent decisions about who they’re going to publish, but they aren’t as able to spread the word as powerfully as a deep-pocketed company. That really affects what consumers are able to read,” he said. “That’s a real impact that everybody sees.”

Others say the story is a bit more complicated than corporate consolidation stomping out all variation and diversity in the business. It’s the best of times and the worst of times in the book industry. It just depends on your perspective, according to Mike Shatzkin, CEO of publishing consultancy The Idea Logical Company.

”The book business as measured in titles has been exploding for 20 years,” he told The Independent. “The book business as measured in dollars has been growing for 20 years.”

He estimates that about 40 times more titles are available than the half a million or so books in print in 1990. It’s just that publishers and bookstores now face competition from self-publishers using services like Amazon’s Kindle Direct, as well as upstarts who, thanks to the internet, now have cheaper access to the same printing and storage supply chains that used to only be affordable to major publishing houses.

Someone looking to sell books doesn’t even need much physical infrastructure at all. They can accept payment for a book, then pass along the printing and shipping order to distributors like Ingram, without ever touching a book themselves.

Even a pandemic couldn’t tank sales, according to Penguin Random House’s Mr Dohle. Print book sales grew by more than 20 per cent between 2012 and 2019 — then another 20 per cent between 2019 and 2021.

To make a profit in a world where, Mr Shatzkin estimates, about 80 per cent of books are sold online, in an essentially limitless variety, with nearly instantaneous printing and shipping, big publishers can only survive, he argues, by consolidating and monetising reliable books already in print from their back catalogues. These books don’t need publishers to shell out lots of money scoring a promising new author and promoting their work.

“The world that we’re in, which we have been in for 20 years, is that the state of the business that belongs to commercial publishers is shrinking, and the ability of publishers to establish a new book as profitable is shrinking, drastically,” he said. “What has grown is the ability to monetise deep backlists that might have never been monetizable in the old days.”

Looming in the background of the merger trial is Amazon, which controls, by some counts, an estimated two-thirds of the market for new and used books in the US, and Ingram, the distributor, a company which controls the majority of independent book distribution between publishers and readers.

By law, mergers present the opportunity for the government to weigh in on whether a proposed company risks becoming anti-competitive, but Amazon has been able to use its numerous different business lines to fund a roaring books business built on titles offered at low prices.

“This particular suit is like chasing something that has escaped a long time ago,” Paul Yamazaki, the book buyer at San Francisco institution City Lights Bookstore, told The Independent, sitting on a sunny porch covered in stacks of books, months before the judge’s ruling. “If the Justice Department was going to really look at this, and look on behalf of the readers and writers, then they should look at Amazon.”

Barring exceptions like the breakup of Standard Oil and the Bell System companies, the government rarely elects to break up monopolies outside of mergers.

Even with advances in self-publishing, e-commerce, and a flourishing of indie bookstores in recent years, many owned by an increasingly diverse group of industry newcomers and people of colour, the e-commercification of publishing has made it hard for small presses to have their books reach readers in stores, Mr Yamazaki said.

“So many of the presses — City Lights, New Direction, Copper Canyon, Coffeehouse — all started out as these kind of homegrown projects with somebody that had a wonderful idea and just only had sweat equity and a typewriter,” he said. “We need the whole ecology to prosper.”

In the present ecology, however, according to Next Chapter’s David Enyeart, the big fish seem to be getting bigger, with few benefits to everyone else down the food chain over the long term. He couldn’t think of a single positive about the proposed merger.

“What we’ll see in the long run is less diversity in offerings, less reason for them to offer better discounts and to generally make room for independent bookstores and the sort of books that we want to promote. That’s really sort of the issue. It’s a long-term sort of thing. It won’t change anything day-to-day,” he said.

“It’s the sort of thing where we’ll wake up in several years, and there’s only two publishers left, and they’re squeezing us hard.”

This article was amended on 23 August 2022. It previously stated that the ex-publisher of Simon & Schuster imprint Gallery Books testified during the merger trial. However, the testimony came from Gallery’s current publisher, Jennifer Bergstrom.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments