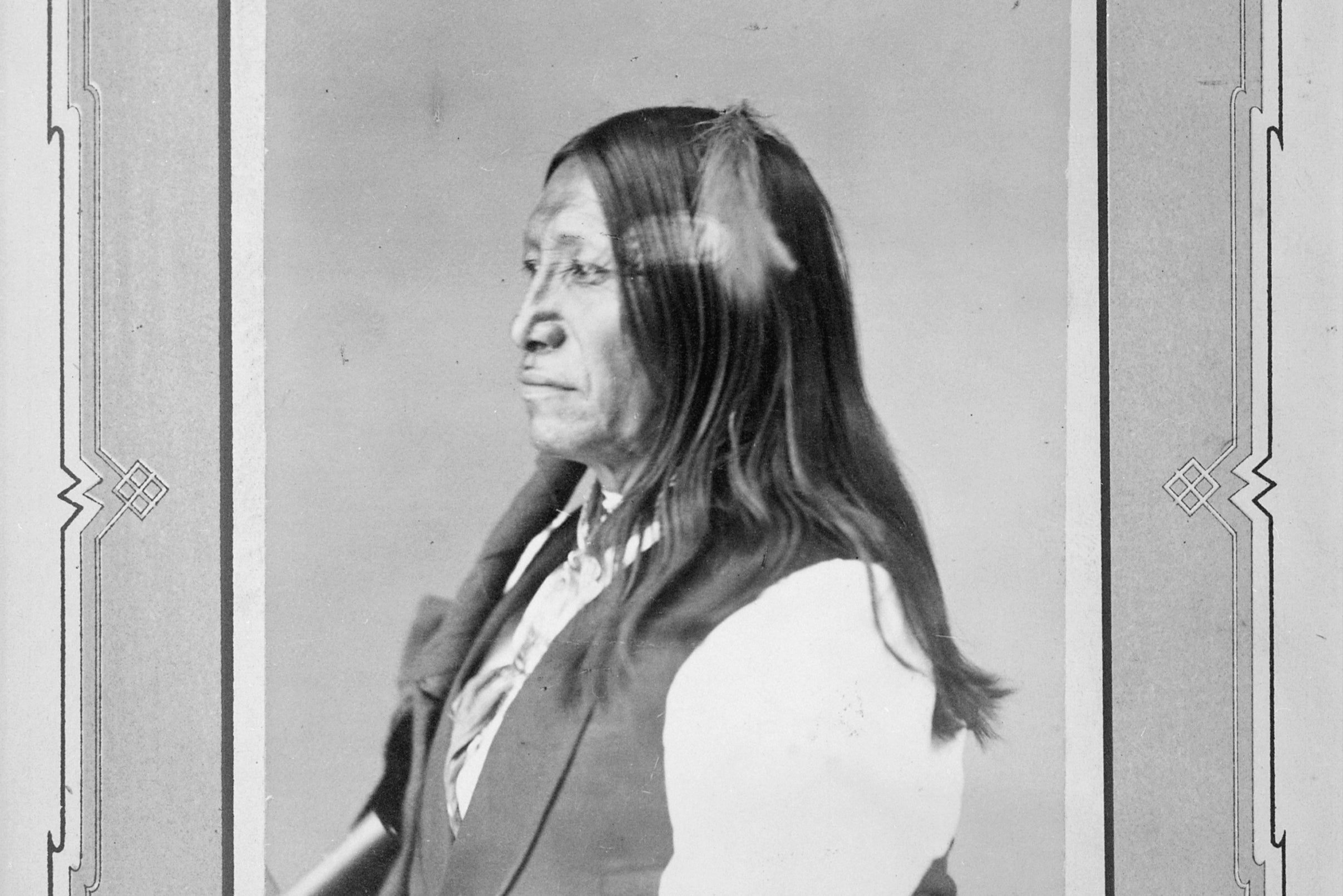

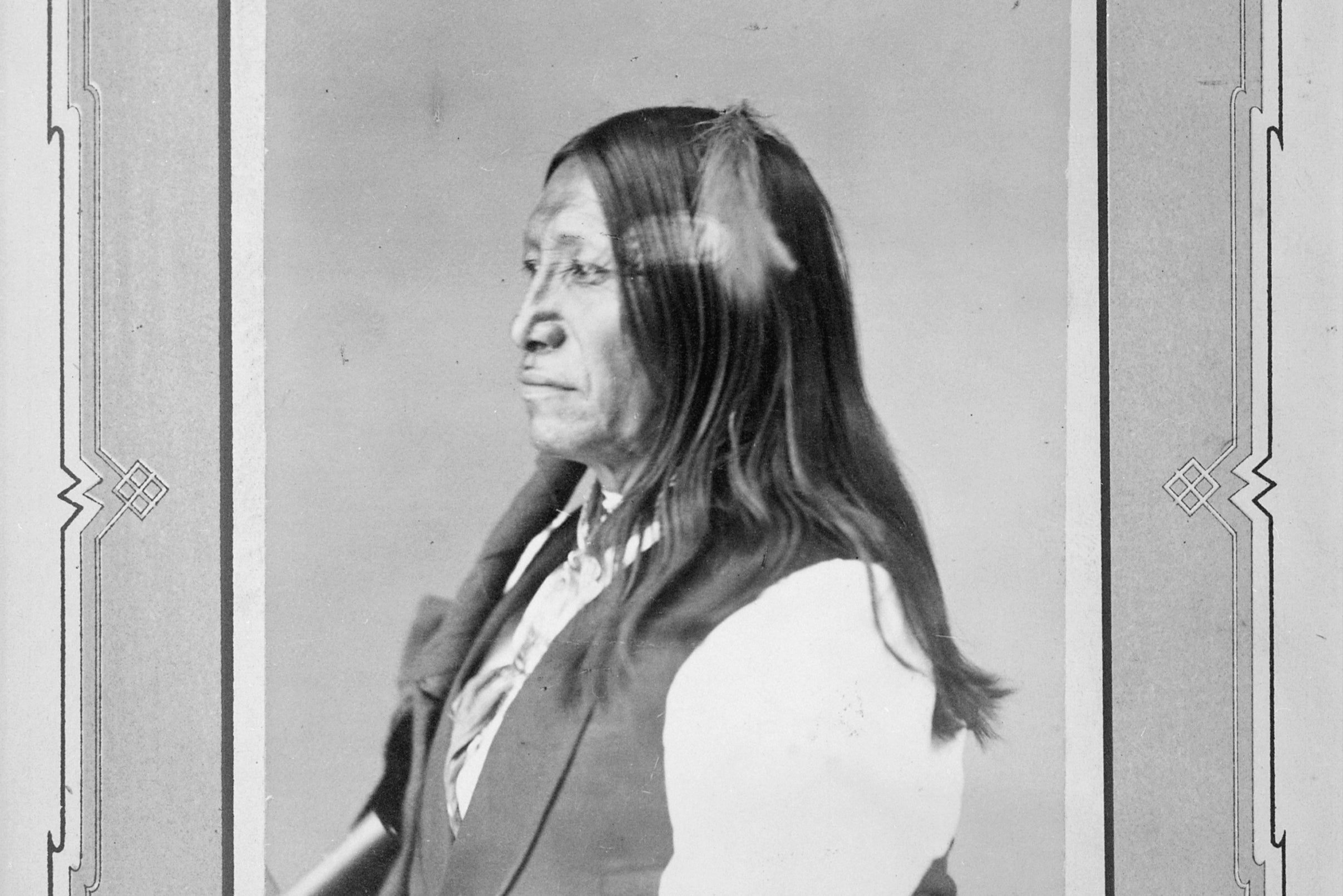

Family returns headdress of famous Lakota chief Spotted Tail that it kept in a suitcase in the closet

Stunning eagle feather headdress that once belonged to Chief Spotted Tail to go on full display next year

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.As Americans gather with families to celebrate Thanksgiving, a holiday rooted in the country’s long, complicated history with its Indigenous people, a remarkable artifact has been on a complex journey of its own.

A stunning eagle feather headdress that once belonged to Chief Spotted Tail (Sinte Gleska), an influential 19th-century Brule/Sicangu Lakota leader, has been returned to the chief’s descendants, who in turn are hoping to preserve the artifacts for public display.

A different family, the Newells, first came to possess the artifacts, including the headdress, a bison horn, and a lock of braided hair, under unclear circumstances in the 1870s, when relative Major Cicero Newell, an Indian agent for the federal government, was serving in what’s now South Dakota.

A century and a half later, his descendants held onto the heirlooms, storing the headdress in a suitcase in a closet in smalltown Washington. In 2020, they set about trying to return the artifacts.

James Newell, 77, connected with John Spotted Tail, a descendant of Chief Spotted Tail, and chief of staff to the tribal president of the Rosebud Sioux Tribe. John Spotted Tail drove across the country to reclaim the objects.

“It felt right,” Newell told The New York Times.

The headdress was formally transferred to the care of the South Dakota Historical Society in May of this year, with plans to fully display it in 2025.

“As custodians of our ancestral heritage, deeply rooted in Sicangu Lakota history, we are profoundly honored to oversee the return of these cherished artifacts belonging to our esteemed ancestor, Sinte Gleska,” Chief John Spotted Tail and his wife, Tamara Stands and Looks Back-Spotted Tail, said in a statement at the time. “It is our heartfelt belief that these items should be shared with all who wish to learn from and honor our shared history, ensuring that the legacy of our people endures for all present and future generations.”

The headdress is a reminder of the complicated, often violent history that accompanied U.S. colonization of North America.

Spotted Tail was one of the signers of the Fort Laramie Treaty of 1868, meant to end conflict between indigenous tribes and U.S. settlers as they continued their relentless expansion westward.

Under the terms of the treaty, the tribes gave up thousands of acres of land that had been promised in earlier treaties but retained hunting and fishing rights, in exchange for the Great Sioux Reservation in what’s now South Dakota, including the Black Hills.

The U.S. nonetheless facilitated mining expeditions into the Black Hills. Once gold was discovered there, miners moved onto Sioux hunting grounds and sought protection from the U.S. Army, and the U.S. government eventually confiscated the Black Hills in 1877, according to the National Archives.

Spotted Tail was also a signatory on a letter to the Commissioner of Indian Affairs in 1881 regarding the dismal state of the government’s boarding schools for Indigenous children, institutions Indian agents like Cicero Newell helped convince tribes to send their children to.

“We cannot bear to hear of the sickness and deaths of our children and we want you to listen to our words,” the letter to the commissioner reads.

Subsequent historical investigations have revealed widespread abuse, disease, and death at such boarding schools, which the U.S. pursued to force the assimilation of indigenous tribes.

Cicero Newell, for his part, admired Spotted Tail, once writing that in heaven, “I hope that one of the first persons I may meet there will be my dear old friend Spotted Tail.”

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments