They received reparations in 2022. Did it really change their lives?

In January 2022, the town of Evanston in Illinois began giving out thousands of dollars to residents who had been affected by slavery. Now, San Francisco is planning to follow their lead. Andrew Buncombe reports on the repercussions — both personal and political — of the payments

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

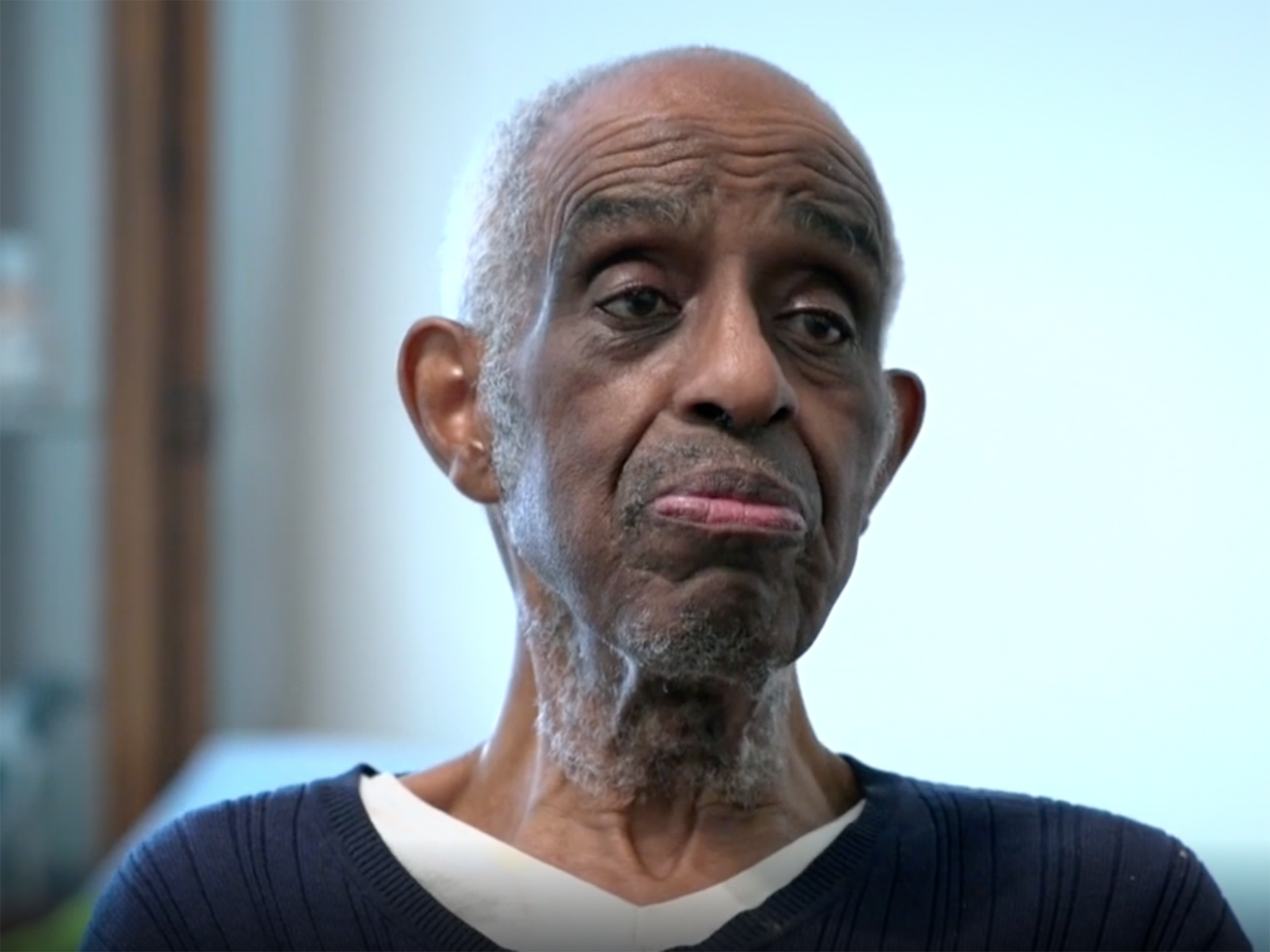

Your support makes all the difference.Louis Weathers didn’t know what to think when he heard he was going to receive reparations for slavery.

He had listened to people talking about reparations — people such as Representative Eleanor Holmes Norton — during the two decades he’d lived in Washington DC. But it was always couched as a demand, or an aspiration: something that might happen in a far-off place or a far-off time, not one still so wounded by the impact of America’s “original sin”.

Weathers’ mother, when pregnant, was forced to travel to a neighboring town to give birth because the hospitals where she lived would not accept African Americans. Weathers was under no illusions as to how hard it would be for society to throw off the cloak of bigotry. And yet there it was: his name, on the list of 16 people who had been selected for a payment.

“I didn’t believe it,” says Weathers, now aged 87. “The next thing I thought was, weren’t we meant to get 40 acres and a mule? I was going to keep the acres and give away the mule!”

Weathers, a military veteran who served in the Korean War, was among the very first people to receive a reparations payment, more than 500 years after the start of the trans-Atlantic slave trade and 156 years after slavery’s formal abolition in the United States. He was eligible to receive one because of where he lived. In 2019, the city of Evanston, Illinois, established a committee to fund and administer reparations to those of its 70,000 residents who met certain criteria.

To apply, the Black Evanstonians had to fit one of three categories. They could either be residents who lived in the city between 1919 and 1969, referred to as “ancestors”; or direct descendants of a Black resident from 1919 to 1969; or else they could submit evidence that they had suffered housing discrimination due to the city’s policies after 1969. There was a requirement that the money be used to help pay for housing costs.

Activists said the payments — the first of which were made to recipients in January 2022 — were proof of what can happen when a local community decides to stop talking about something and act. What they had not anticipated was that the actions of a small city located on the shores of Lake Michigan would reverberate so widely.

Dozens of other communities across the country have been in contact with the people in Evanston, asking for advice on how to establish their own reparations program. In January, a reparations advisory committee in San Francisco, the largest US city yet to adopt a plan, recommended a one-off payment of $5 million to each eligible Black resident. The committee said the payment would “compensate the affected population for the decades of harms that they have experienced and will redress the economic and opportunity losses that Black San Franciscans have endured, collectively, as the result of both intentional decisions and unintended harms perpetuated by city policy”.

Rev. Michael Nabors, a senior pastor of Second Baptist Church of Evanston and President of the Evanston NAACP, says the city now hosts an annual reparations summit to help other communities. Every year, more people attend. Right now, he says, 400 communities and municipalities are looking into local reparations — and of those, at least 100 already have established committees to investigate how to proceed.

“So we started the process and it kicked off with a bang at a town hall meeting in November of 2019,” he says. “It’s exciting for us to meet all these wonderful people from Amherst and Boston, Los Angeles and San Francisco, and every place in between — north, south, east and west are coming to the table.”

He says the Evanston model cannot be replicated everywhere. His is a small, progressive city with near-unanimity among local officials on pushing forward the plan: “What we do is try and help people identify what the special traits or qualities are about their particular town, and then to go on from there.”

From 40 acres and a mule to true reparations

Evanston’s success might suggest reaching this point has been easy. The truth is, it has been anything but.

Even though the town is considered a successful example of how reparations can be meaningfully made, it has run into logistical problems. A month ago, the Washington Post reported that Evanston had spent only $400,000 of the $10 million made available for reparations payments. There remains a waiting list of hundreds of people; Louis Weathers and his 15 compatriots who have received the funds are in the minority.

Nevertheless, the small town of 78,000 is being upheld as a national example and used as a blueprint for further efforts to do the same — including, most famously, in San Francisco.

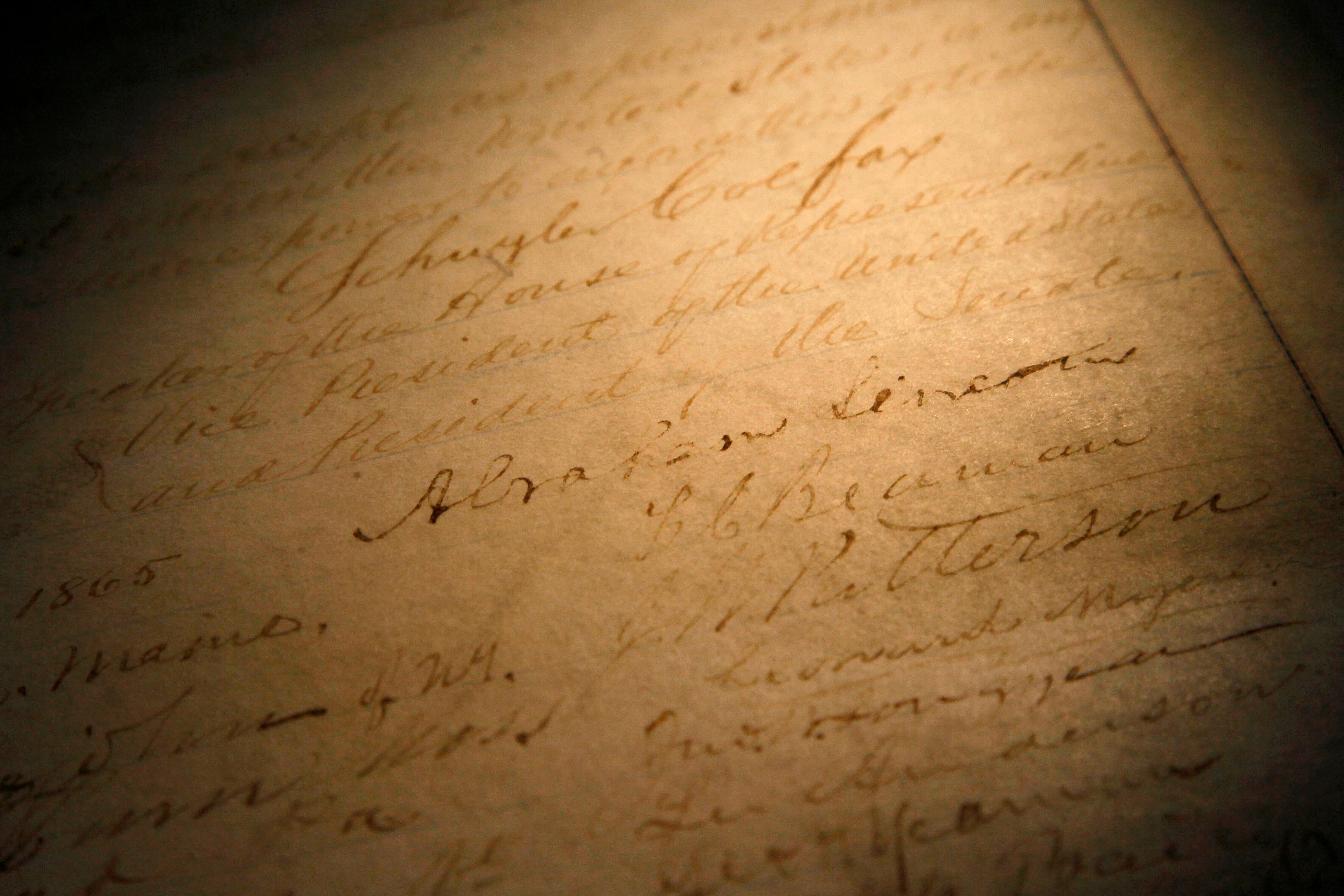

To truly understand how reparations work and why they are so regularly a hot topic for political debate in the US, it’s important to look back. Discussion about paying reparations to those whose ancestors were taken from Africa and forced into slavery began at the time of abolition and the end of the Civil War. The order for “forty acres and a mule” was signed by Union general William Sherman in January 1865, with the idea that land be given to newly freed families.

For a dozen of so years at the end of the war — a period now termed the Reconstruction — land was distributed across the country and a series of amendments were made to the Constitution that, in theory, gave Black Americans the same rights as every other citizen. It was the briefest of periods of optimism. After President Abraham Lincoln’s assassination, President Andrew Johnson reversed Sherman’s order and returned land back to former slave owners.

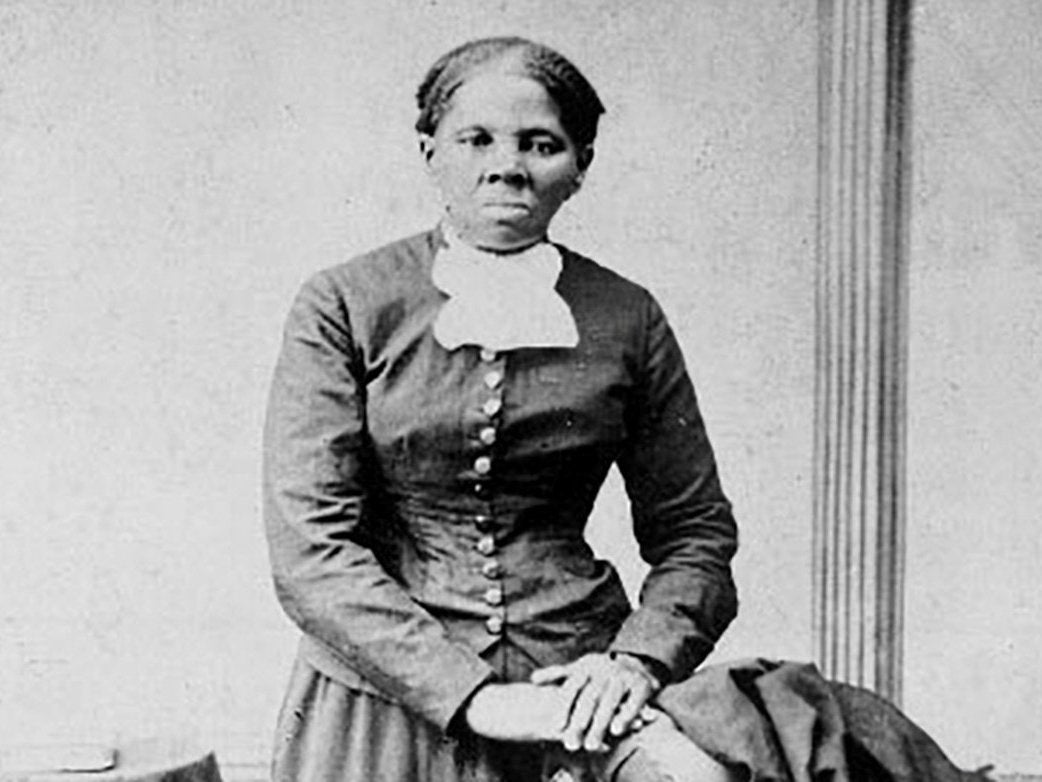

By 1877, a deal between Democrats and Republicans led to the withdrawal of Union troops from the areas they had won and the rapid reemergence of white power in the formerly Confederate South. That set in motion the Jim Crow era of enforced segregation, bonded labor in the cotton industry, and the establishment of a penal system that made use of prison labor, overwhelmingly comprised of African Americans. This era would continue for over another 100 years. Through the blood and efforts of abolitionists such as Harriet Tubman, it would be forced to an end during the civil rights movement, during which the Civil Rights Act of 1965 was passed, forbidding efforts to stop Black people from voting.

The first measure tabled in Congress to study reparations didn’t come until 1989, when it was brought to the floor by Michigan Congressman John Conyers. He then reintroduced it at every Congress until his death in 2019. Since then, the job has been taken up by fellow Democrat congresswoman Sheila Jackson Lee of Texas. Her proposal, House Resolution 40, better known as HR 40, calls on the president to “establish by executive order a federal commission that would study the legacy of enslavement and develop proposals for reparations”.

To a current generation of activists — writers such as Ta-Nehisi Coates, who in 2014 penned a celebrated essay in The Atlantic called the The Case for Reparations — the moral case for payments is obvious. He wrote: “Until we reckon with our compounding moral debts, America will never be whole”.

Since then, the argument ought to have become ever clearer.

Two events — the Covid pandemic, and the 2020 killing by police of George Floyd — forced millions in the nation to consider the issue of racial justice. The murder of Floyd, essentially choked to death by a white police officer in Minneapolis as members of the public looked on and recorded on their phones, became shorthand for a criminal justice system that had long discriminated against people of color, based as it was on many of the Jim Crow-era laws intended to suppress and control African Americans.

Meanwhile, the pandemic, which had a much greater impact on people of color, and most of all Black people, forced some to confront the utterly unequal economic status such communities are trapped in. Studies show that centuries of laws such as redlining — which made it harder for Black people to own homes and establish intergenerational wealth — has created a situation where the average white American family has roughly 10 times as much wealth as the typical African American family and the typical Latino family.

“In other words while the median white household has about $100,000 to $200,000 net worth, Blacks and Latinos have $10,000 to $20,000 net worth,” said an account of a study by Harvard University.

Despite these facts, data and anecedotal experiences, polls suggest many white Americans have no interest in reparations, and “do not want to drag up the past”. Indeed, across the country, white politicians seek to prevent even the teaching of a complete history of America, claiming white students should not be “made to feel bad” about what happened before them.

It is perhaps little surprise that a 2021 survey by Pew found only 30 per cent of Americans think descendants of people enslaved should be repaid in some way, such as given land or money. Around 70 per cent say they should not.

Again unsurprisingly, the results split across lines of race. It found 77 per cent of Black people supported reparations, while just 18 per cent of white Americans felt the same. Support among Democrats was much greater than among Republicans. Younger people are also notably more in favor of reparations than those aged 65 and above.

How Evanston took practical action

The activists in Evanston were adamant not to be intimidated — and thus paralyzed into inaction — by the scale of the problem.

When they tried to look at the issue of slavery in its entirety — a transatlantic trade that took an estimated 12.5 million men, women and children and deposited them in North America, with millions more taken to Latin America — the task felt overwhelming. Historians believe the first African slaves were brought to Santo Domingo, on what is now the Dominican Republic, in 1525. The first slaves to arrive on the US mainland — a group of between 20 and 30 — arrived in 1619 at Fort Monroe in Hampton, Virginia. The last slave ship, the Clotilda, docked at Mobile, Alabama in either 1859 or 1860, five years before abolition. It carried 110 people. That year also marked the last known major slave auction, in Savannah, Georgia.

“The total debt owed to Black America is immeasurable,” says Robin Rue Simmons, a former council member, or alderperson, from Evanston, and the founder of the non-profit FirstRepair. “You can look at closing the wealth gap, you can look at other ways of repairing the harm. But the total harm is in every area of liveability of our lives. And so getting to a remedy, I think, is a challenge for many.”

“We have to take a first step towards repair and not be paralyzed in the breadth and scope of the work needed to repair, and start someplace so that we can build upon the work as in every other policy that we’ve done,” she adds.

But Simmons — who once represented Evanston’s fifth ward and who now advises communities across the country on reparations — says while it is important to work locally, the size of the problem demands a federal, nationwide redress.

In Evanston, they voted to pay for reparations using a tax on cannabis sales, after the drug was legalized in Illinois in January 2020. “So we’re seeing progress and opportunity locally but this is a national issue. It is a 400-plus year national crisis of crimes against Black people,” she says.

Simmons’ aim is for the Biden administration to get busy. Evanston is no more capable of addressing the scale of the problem than any other city.

“These are federal crimes, federal harms, federal legislation, a nation that was built on oppression, discrimination and the theft of black labor,” she says. “So we want to see a federal response to reparations and we are standing together behind Congresswoman Sheila Jackson Lee and calling on President Biden to sign an executive order for HR 40.”

During his campaign for the presidency, Biden said he supported the idea behind the push for reparations, as did Kamala Harris. Yet, the bill has never progressed very far.

A sister bill in the Senate, the first ever, was tabled by Cory Booker. It secured 12 co-sponsors, but has not moved forward since then. This year, Republicans retook control of the House, meaning HR 40 has even less chance of being voted on. If Republicans retake the Senate in 2024, as many believe they will, the issue will be pushed back even further.

The time for talk, says Simmons, is over: “We live in the consequences of the transatlantic slave trade. We see it in the wealth gap, in the life expectancy gap, in the education divide, and so on. So too much study. We don’t need much more study; we need action right now.”

Taking Evanston’s model to San Francisco: ‘Don’t let this so-called progressive, liberal brand spin and deceive you’

Rev. Amos Brown feels the similar way. The 81-year-old was born and raised in Mississippi and has been a pastor at the Third Baptist Church of San Francisco since 1976. He is also a member of the reparations task force.

“We are in constant deliberation and discussion, but the hard work is just beginning,” he says.

Why is that the case?

It’s challenging to “get the American public, the public of San Francisco, to admit, to atone, to act — those three A’s,” he says. “To admit that not during the days of enslavement or segregation, but to admit that it is wrong down to this day.”

Brown, whose grandfather was a slave, refers to a survey reported by the Wall Street Journal. The results of that survey showed the 20 worst cities for Black Americans in terms of poverty, education, income, home ownership, unemployment, mortality, and incarceration, compared to their white counterparts. “San Francisco was 17,” he says. “Don’t let this so-called progressive, liberal brand spin and deceive you.”

San Francisco has the smallest Black population of any large city in the country, and, Brown says, lost a large portion of its African American population to so-called gentrification and rising housing costs over the last 30 years. Figures from the US Census Bureau suggest the Black population in the city today represents only 6 per cent of the total, down from more than 13 per cent in 1970. “That tells us something is wrong in the state of Denmark,” Brown adds, with a Shakespearean flourish.

Does he believe that, if the city’s experiment is successful, it could set an example for others?

Brown says he is doubtful. The House of Representatives he says, is filled by the likes of far-right Georgia Congresswoman Majorie Taylor Greene, the likes of which he thinks are “downright mean”.

“They’re saying they don’t have enough time to study it,” he adds with some disdain, before reeling off a list of previous investigations into the disparity between Black people and white people that go back as far as the Kerner Report of 1967. “It’s time for us to stop studying and to get some traction and action.”

A solution that doesn’t solve everything

Experts have pointed out that a key factor in continuing the economic inequality between Black people and white people has been the historical barriers enacted to prevent Black people buying and owning property, oftentimes a foundation to intergenerational wealth.

From redlining to a bank’s refusal to give a loan, African Americans have historically been consigned to the bottom of the housing ladder. This is why the city of Evanston decided the first payments of reparation had to be spent on housing — either for rent, mortgage payments, another housing-related loan, or else a repair to their home.

Academic Dr Andre Perry, a scholar-in-residence at American University in Washington DC and author of “Know Your Price: Valuing Black Lives and Property in America’s Black Cities”, says it is likely that projects in places such as Evanston will add to pressure for a national response.

“I think many of the reparations programs will bubble up to the federal level, and create a sort of groundswell of support,” he says. “We’re seeing that now. Support for reparations hovered around 10 per cent 25 years ago. Now it’s well in the 30s. Not only will you build support by advocating for reparations at the local level, you’re building a suite of ideas that can eventually be resourced and codified by federal policy.”

Louis Weathers, who has three children, was able to loan the money to his eldest son, Michael, to allow him to reduce the mortgage on his own apartment.

A report in the Evanston Roundtable noted Weathers’ parents moved to the city from the South in 1932 and bought the property he still lives in. He was born three years later in Cook County Hospital in Chicago, because Evanston Hospital was segregated.

Does he remember suffering racial discrimination while growing up?

“I’ve been living with discrimination all my life,” he says.

He says he had to go to a segregated elementary school for Black children, but that the high school was integrated as there was only one. “But growing up, discrimination was all around us. We used to go to movies, we had to sit on the second floor and all that stuff. So I faced discrimination in my life,” he adds.

Does he think the situation has improved?

“It’s better in a lot of areas but discrimination and racism is still exists,” he says. “Things are better for my kids and my grandkids. They can achieve things, maybe not as fast and not as much, but it’s not worse for them.”

His eldest son, Michael, who is 61 and a state of Illinois employee, learned last year that he, too, had secured a $25,000 reparations payment. He said he would use the money to pay off his mortgage.

Another recipient, Ramona Burton, says her mother also had to travel to Chicago to give birth to her. Burton was the youngest of six children and that her parents were from North Carolina and South Carolina. Her father worked three jobs in order to be able to buy their home.

Burton first heard about the proposed plan for reparations when the actor Danny Glover spoke at an event in Evanston in 2019. “I was very excited and surprised,” she says.

She has used the money she received to complete a series of repairs to her house, including fixing the roof: “I had eight new windows put in, and my chimney fixed, a partial fence, and central air conditioning.”

Burton says she feels she did not encounter prejudice as much as others, although memories come to mind throughout the years. One thing she is adamant about is that no amount of money can address the racism that Black people have had to endure for decades: “I think it’s a start, but I don’t think any amount of money can repay people for all the damage, both physical and psychological, that it did.”

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments