His DNA shows he’s Sitting Bull’s great-grandson. Now he’s on a mission to save his legacy

Exclusive: Ernie LaPointe says it’s time to be truthful about who his great-grandfather really was. Bevan Hurley writes

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

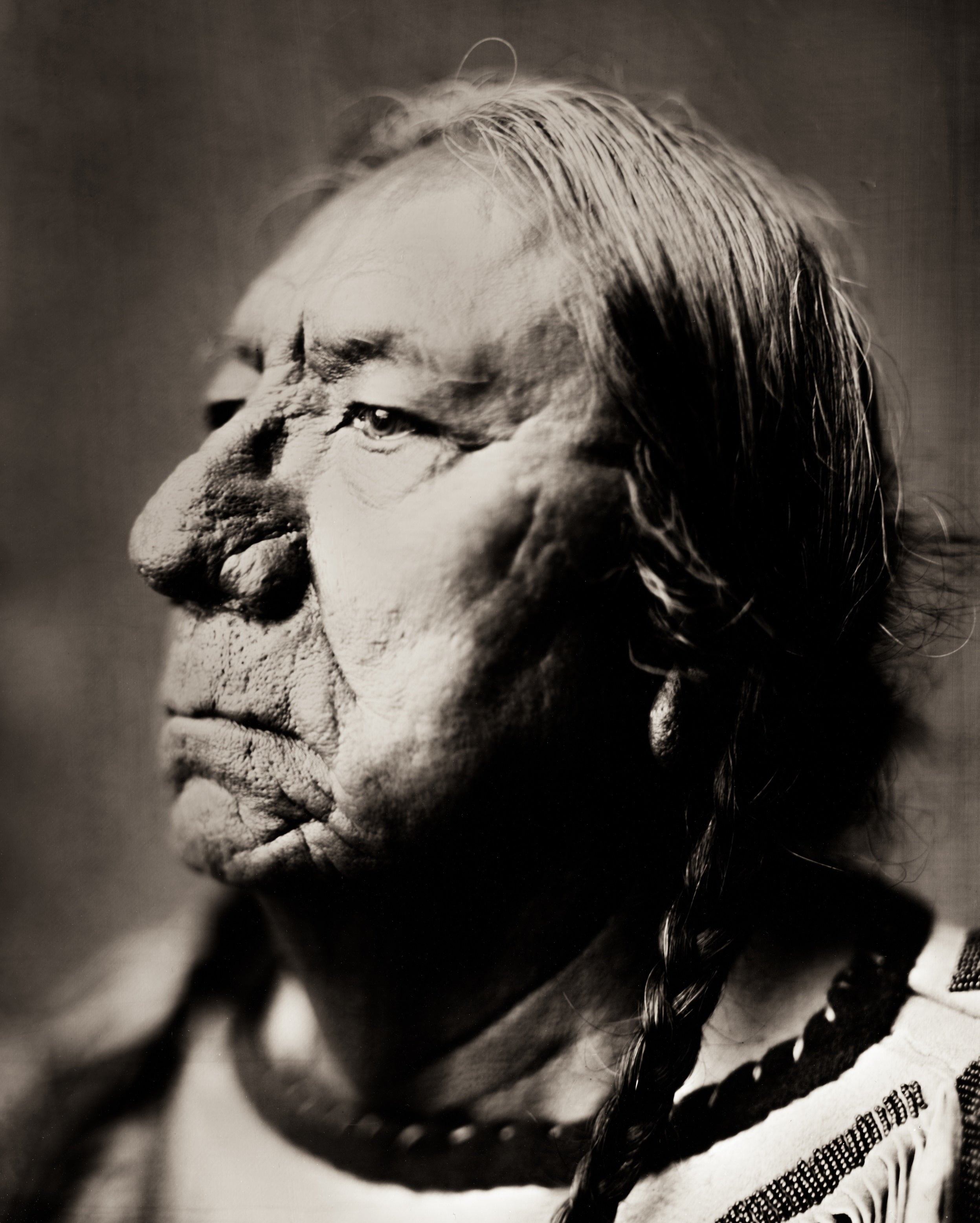

Your support makes all the difference.“I used to feel anger when I was young,” says Ernie LaPointe, who DNA researchers confirmed this week as the great-grandson of the legendary warrior Sitting Bull.

The 73-year-old Lakota elder saw the way his people were portrayed in cinema and popular culture, and it had nothing to do with the oral traditions he learned about from his mother and grandmother.

“I would always look at the movies and I wanted to be John Wayne or Randolph Scott because they were big heroes. And the bad guys were always the native guys.

“That’s just a fantasy these people came up with. If you look at these old Westerns from the 50s even to now, they always make themselves look good and made us look like the villains.

“But actually it’s the other way around. They’re the villains, the rapists, torturers, scalpers and murderers. Not us.”

Mr LaPointe endured childhood battles with alcohol and marijuana, joined the army, and later developed PTSD while homeless.

He overcame it all and for decades now has embraced his culture to lead a life in keeping with the spiritual ways of his ancestors.

He knew from a young age he was the great-grandson of Sitting Bull, the Lakota leader who led a defiant resistance against the US government during a time of brutal war and massacres.

Sitting Bull’s name was Tatanka Iyotake, which translates to Buffalo Bull Who Sits Down, and he was the leader of Hunkpapa Lakota Sioux tribe in the last half of the 19th Century.

In 1876 Sitting Bull led the Lakota tribes in battle against the US 7th Cavalry, defeating General George Custer’s forces at the Battle of Little Bighorn.

After the US Government poured troops into his native lands, he eventually surrendered in 1881, and worked for a time as a performer in Buffalo Bill’s Wild West show. He was murdered on 15 December 1890 at Standing Rock Indian Reservation by Native American police, on the orders of the US military, who were fearful he could lead another uprising.

Growing up, Mr LaPointe was discouraged about talking of his famous ancestor with outsiders.

“Before the Europeans came into our land, there was no doubt when somebody said I was related to somebody because there was no fabrication or bragging about who you were related to.

“Even today we try to explain this to young people. I always tell them make sure you find out who their ancestors are, you might be related. This was a way for the Lakota people when you’re trying to pick up a girl or a guy, you’re not related to them. This is one of the oldest traditions in the Lakota culture.”

That all changed in 1992 when he “came out of the shadows to try to tell the truth about who my great-grandfather was”.

It was time to set the record straight.

In 2009 he published his own book Sitting Bull: His Life and Legacy, which was later turned into the documentary Sitting Bull’s Life.

Since then he has tried to educate the world about his great-grandfather’s legacy, travelling all over the world to give lectures and promote his culture.

And yet, the doubters persisted to question his true identity.

The idea to test DNA extracted from a piece of hair belonging to Sitting Bull came in 2007. The hair had been stored for over a century at room temperature in Washington’s Smithsonian Museum before it was returned to Mr LaPointe and his sisters.

Researchers from Cambridge University led by professor Eske Willerslev used an innovative technique that compared DNA from a fragment of Sitting Bull’s scalp lock to Mr LaPointe’s genetic data.

“Back in the 1800s they used cyanide to coat the hair to look shiny. You had to remove that to get to the DNA inside the hair,” says Mr LaPointe.

It took 14 years to find a way of extracting DNA from a 5-6cm piece of Sitting Bull’s hair as it was extremely degraded.

For Mr Lapointe, it was a chance to silence any lingering questions.

“Throughout the last 40-50 years, people always try to dispute, say you’re wrong. You can have critics around that try to dispute the DNA. But Eske Willerslev covered his bases.

“It solidifies it for me. It shouldn’t have gone this far. If I told you I was related to Sitting Bull, I wouldn’t lie to you.”

Mr LaPointe says virtually all of what has been taught and portrayed about his great-grandfather’s life came from Stanley Vestal’s 1932 book Sitting Bull, Champion of the Sioux.

Dozens of authors based their own books on Sitting Bull from Vestal’s work, which was an utterly flawed piece of research, according to Mr LaPointe.

“Stanley Vestal never interviewed the descendants of Sitting Bull. He interviewed the murderers of SB. That’s where he got his story from.”

For a while he gave lectures at Battle of Little Bighorn site in Montana. But he says his home truths didn’t go down well with US historians.

“They just try to glorify Custer,” he says of the accepted mainstream version of the battle.

“The historians sit down and write the history of themselves and they make it look like they’re the greatest people in the world which they’re not. They’re the biggest low lives in the world.

“They have to answer for themselves. My goal is to awaken within them a spiritual connection as to why they should be who they are.”

He says his people have been trying to atone for the mistakes of the past, such as when they scalped US soldiers after the Battle of Little Bighorn.

“We ended up losing our prestigious standing in the eyes of the great spirit. We have been atoning for that, but the Americans don’t atone.

“I don’t hold any animosity to these people. I don’t talk to them, I talk to my spirits, and I said to the spirits ‘I have pity on these people’.

“What they have over the past 549 years they have been in this country, they are going to have to answer for this, and it’s coming close. They keep teaching their young the same old same old. They live in the past. They look at yesterday to improve tomorrow which will never happen. I tell them you should look to the future.”

Mr Lapointe says Americans are too caught up in attaining material wealth.

“When they die they don’t go to the spirit world, they haunt their house, or they haunt their car, or their bank account.

“They have no culture. Their culture is made up of their constitution, their bible, their flag. That’s it. With us it’s unseen, it’s unwritten. It’s what you learn in the ceremonies. What you take to the future. The past is gone. You can never change tomorrow by looking at this morning.”

He says is his famous ancestor was alive today, he would probably feel despondent at what the world had become.

For Mr LaPointe, it’s about trying to influence the next generation.

“I’m trying to pass it on to everyone, not just my own children and grandchildren. It’s up to them, not me.”

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments