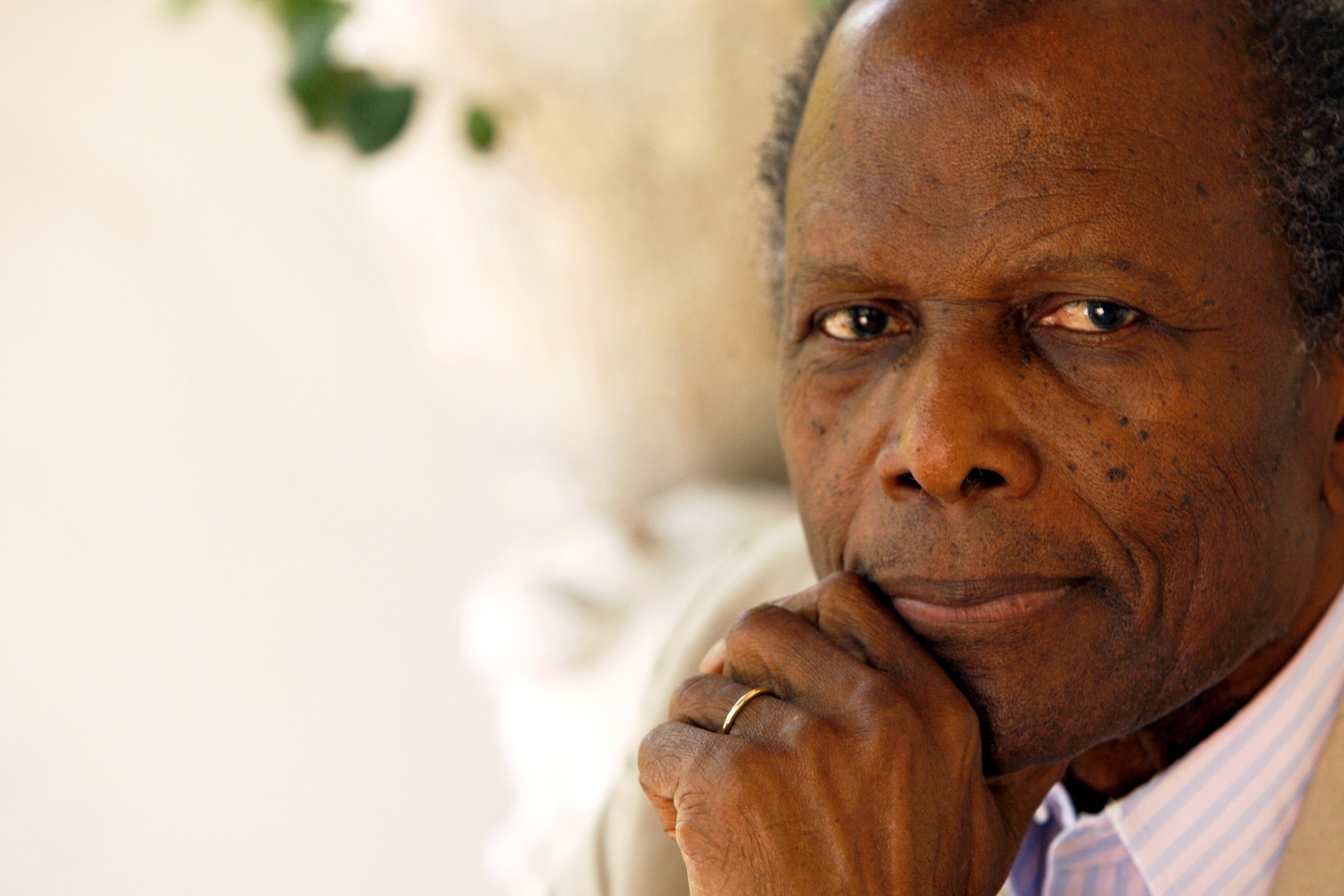

Oscar winner and groundbreaking star Sidney Poitier dies

Sidney Poitier, the groundbreaking actor and enduring inspiration who transformed how Black people were portrayed on screen and became the first Black actor to win an Academy Award for best lead performance and the first to be a top box-office draw, has died

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Sidney Poitier the groundbreaking actor and enduring inspiration who transformed how Black people were portrayed on screen and became the first Black actor to win an Academy Award for best lead performance and the first to be a top box-office draw, has died. He was 94.

Poitier, winner of the best actor Oscar in 1964 for “Lilies of the Field,” died Thursday at his home in Los Angeles, according to Latrae Rahming, the director of communications for the Prime Minister of Bahamas

Few movie stars, Black or white, had such an influence both on and off the screen. Before Poitier, no Black actor had a sustained career as a lead performer and rarely was one permitted a break from the stereotypes of bug-eyed servants and grinning entertainers.

Poitier, the son of Bahaman tomato farmers, appeared in more than 25 films during the 1950s and 1960s and his rise paralleled the growth of the civil rights movement. As racial attitudes evolved and segregation laws were challenged and fell, Poitier was the performer to whom a cautious Hollywood turned for stories of progress.

He was the escaped Black convict who befriends a racist white prisoner (Tony Curtis) in “The Defiant Ones.” He was the courtly office worker who falls in love with a blind white girl in “A Patch of Blue.” He was the handyman in “Lilies of the Field” who builds a church for a group of nuns.

With his handsome, flawless face, intense stare and disciplined style, Poitier was for years not just the most popular Black movie star, but the only one.

“I made films when the only other Black on the lot was the shoeshine boy,” he recalled in a 1988 Newsweek interview. “I was kind of the lone guy in town.”

Poitier peaked in 1967 with three of the year’s most notable movies: “To Sir, With Love,” in which he starred as a school teacher who wins over his unruly students at a London secondary school; “In the Heat of the Night,” as the determined police detective Virgil Tibbs; and in “Guess Who’s Coming to Dinner,” as the prominent doctor who wishes to marry a young white woman he only recently met, her parents played by Spencer Tracy and Katharine Hepburn in their final film together.

His unique appeal brought him the same burdens as other pioneers such as Jackie Robinson and the Rev. Martin Luther King Jr. He was subjected to bigotry from whites and accusations of compromise from the Black community. Poitier was held, and held himself, to standards well above his white peers. He refused to play villains or cads and took on characters, especially in “Guess Who’s Coming to Dinner,” of almost divine goodness. He developed an even, but resolved and occasionally humorous persona crystallized in his most famous line — “They call me Mr. Tibbs!” — from “In the Heat of the Night.”

But even in his prime he was criticized for being out of touch. He was called an Uncle Tom and a “million-dollar shoeshine boy.” In 1967, The New York Times published Black playwright Clifford Mason’s essay, “Why Does White America Love Sidney Poitier So?” Mason dismissed Poitier’s films as “a schizophrenic flight from historical fact” and the actor as a pawn for the “white man’s sense of what’s wrong with the world.”

Stardom didn’t shield Poitier from racism or condescension. He had a hard time finding housing in Los Angeles and was followed by the Ku Klux Klan when he visited Mississippi in 1964, not long after three civil rights workers had been murdered there. In interviews, journalists often ignored his work and asked him instead about race and current events.

“I am an artist, man, American, contemporary,” he snapped during a 1967 press conference. “I am an awful lot of things, so I wish you would pay me the respect due.”

Poitier was not as engaged politically as his friend and contemporary Harry Belafonte, but he participated in the 1963 March on Washington and other civil rights events, and as an actor defended himself and risked his career. He refused to sign loyalty oaths during the 1950s, when Hollywood was blacklisting suspected Communists, and turned down roles he found offensive.

“Almost all the job opportunities were reflective of the stereotypical perception of Blacks that had infected the whole consciousness of the country,” he recalled. “I came with an inability to do those things. It just wasn’t in me. I had chosen to use my work as a reflection of my values.”

Poitier’s films were usually about personal triumphs rather than broad political themes, but the classic Poitier role, from “The Defiant Ones” to “In the Heat of the Night,” seemed to mirror the drama King played out in real life: A composed Black man — Poitier became synonymous with the word “dignified — who shames the whites opposed to him.

His screen career faded in the late 1960s as political movements, Black and white, became more radical and movies more explicit. He acted less often, gave fewer interviews and began directing, his credits including the Richard Pryor-Gene Wilder farce “Stir Crazy,” “Buck and the Preacher” (co-starring Poitier and Belafonte) and the Bill Cosby comedies “Uptown Saturday Night” and “Let’s Do It Again.”

In the 1980s and ’90s, he appeared in the feature films “Sneakers” and “The Jackal” and several television movies, receiving an Emmy and Golden Globe nomination as future Supreme Court Justice Thurgood Marshall in “Separate But Equal” and an Emmy nomination for his portrayal of Nelson Mandela in “Mandela and De Klerk.” Theatergoers were reminded of the actor through an acclaimed play that featured him in name only: John Guare’s “Six Degrees of Separation,” about a con artist claiming to be Poitier’s son.

In recent years, a new generation learned of him through Oprah Winfrey, who idolized Poitier and chose his memoir “The Measure of a Man” for her book club. He also welcomed the rise of such Black stars as Denzel Washington, Will Smith and Danny Glover: “It’s like the cavalry coming to relieve the troops! You have no idea how pleased I am,” he said.

Poitier received numerous honorary prizes, including a lifetime achievement award from the American Film Institute and a special Academy Award in 2002, on the same night that Black actors won both best acting awards, Washington for “Training Day” and Halle Berry for “Monster’s Ball.”

“I’ll always be chasing you, Sidney,” Washington, who had earlier presented the honorary award to Poitier, said during his acceptance speech. “I’ll always be following in your footsteps. There’s nothing I would rather do, sir, nothing I would rather do.”

In 2009 President Barack Obama, whose own steady bearing was sometimes compared to Poitier’s, awarded him the Presidential Medal of Freedom, saying that the actor “not only entertained but enlightened... revealing the power of the silver screen to bring us closer together.”

Poitier also wrote a novel, “Montaro Caine,” and tended to family, travel, hobbies and diplomacy. As a citizen of the Bahamas, he was appointed in 1974 Knight Commander of the Order of the British Empire. In 1997, he was appointed the Bahamas’ ambassador to Japan, and later served as ambassador to UNESCO.

Poitier had four daughters with his first wife, Juanita Hardy, and two with his second wife, actress Joanna Shimkus, who starred with him in his 1969 film “The Lost Man.” His daughter, Sydney Tamaii Poitier, appeared on such television series as “Veronica Mars” and “Mr. Knight.”

___

AP writer Robert Gillies in Toronto and AP Film Writer Jake Coyle and former Associated Press Writer Polly Anderson in New York contributed to this report.