Schools teaching 13-year-old students consent in bid to tackle sexual assault

Maryland schools join 11 others states which teach consent in schools

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

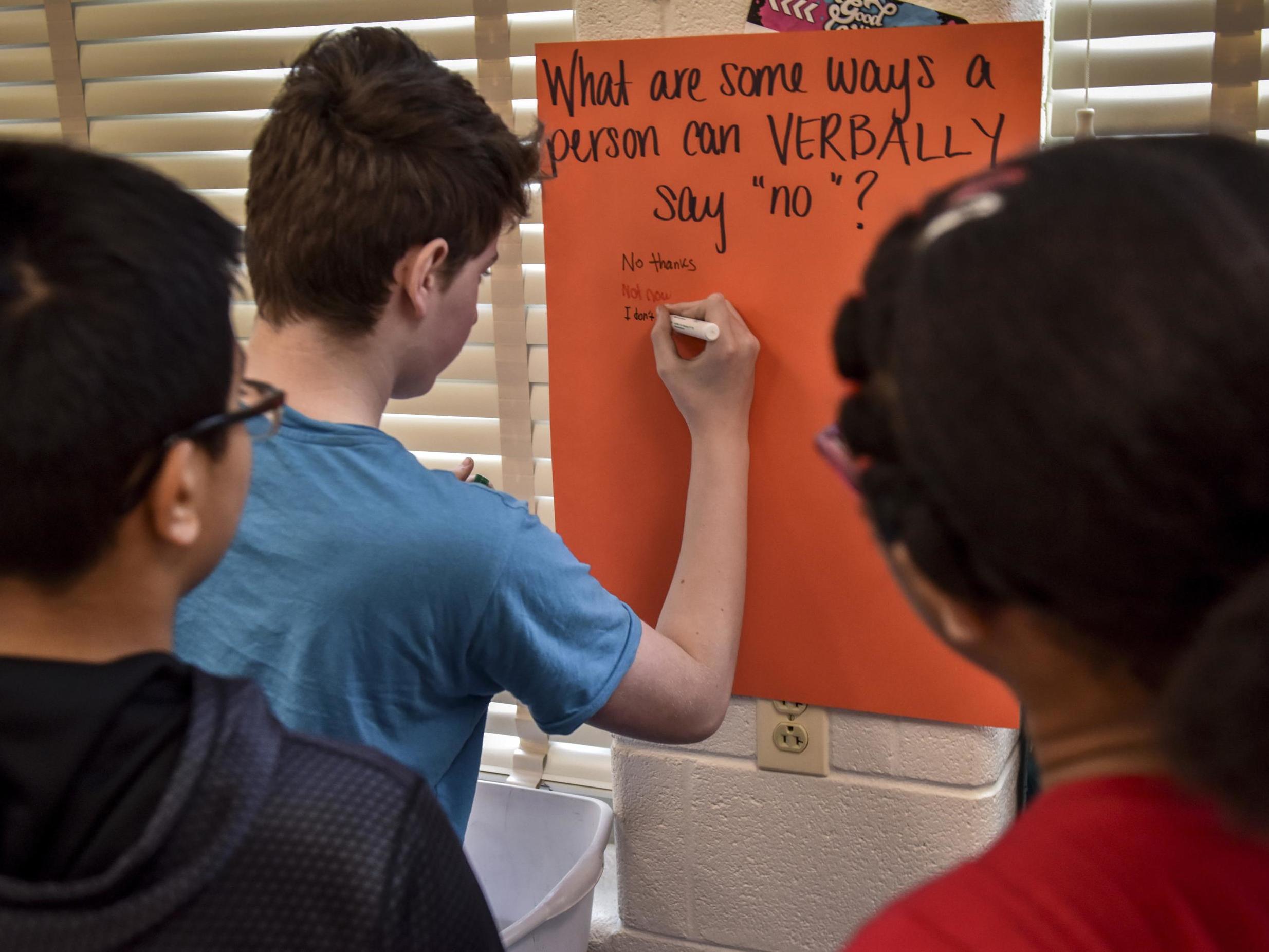

Your support makes all the difference.Huddled around a table in their second-period health class, the seventh graders debated the scenario in a lesson about consent.

It involved a story about a boy named Jack and a girl named Brenda. Jack is helping Brenda with her Spanish homework in the library. Suddenly, Jack starts kissing her. Brenda likes Jack, but she is worried about being caught. “Someone might see us,” she whispers to him. “So be quiet,” Jack responds.

The students at this suburban Maryland middle school were stumped.

“I don't know if that's consent or not,” a girl at the table said.

“That's not consent,” replied a boy next to her, nibbling on the strings of his Nintendo 64 hoodie. “She never said 'OK, let's do it.' ”

“That's true, he didn't ask,” the girl responded. “But she likes Jack!”

“But she doesn't give consent to Jack to kiss her,” another boy responded.

For a growing number of American teenagers, this is sex ed in the #MeToo era.

In 2018, months after allegations against Hollywood film producer Harvey Weinstein set off a nationwide reckoning with sexual assault, Maryland passed a bill requiring that sex education classes include lessons on the meaning of consent.

At the time, only about 11 states and the District of Columbia included references to consent, healthy relationships or sexual assault in their sex education standards, according to the Centre of American Progress. Lessons on preventing sexual assault had most often taken place on college campuses.

But educators across the country have said that waiting until college is too late to prevent sexual violence.

Propelled by student activists and a wave of newly elected female lawmakers, at least 10 more states have enacted laws adding language about consent or healthy relationships to their standards, including Virginia, Colorado and Illinois. But about half of states do not mandate sex education at all.

Now, as Harvey Weinstein faces a criminal trial in New York over charges of rape and sexual assault, the real impact of the #MeToo movement is beginning to take shape in middle school classrooms such as Courtney Marcoux's.

On a recent Monday, Ms Marcoux stood outside of her classroom at Hallie Wells Middle School in Clarksburg, Maryland, next to a handwritten sign.

“CHOOSE how to greet me this morning,” the poster said.

It offered the seventh-grade students three options: Smile and say “Good morning, Mrs. Marcoux,” give her a high five, or give her a hug.

The students shuffled in, juggling 4-inch binders while high-fiving their teacher and grinning brace-filled smiles. A girl in the corner dabbed her lips with a tube of pink gloss. And over the sound of an electric pencil sharpener, Marcoux asked her students her first question of the class:

“What is a boundary?”

“Something that holds you back?” one boy responded.

“A limit,” said another.

“A limit set by whom?”

A girl in the front raised her hand. “Yourself?” she responds.

Marcoux reminded the students about the sign outside the classroom. “You had a choice today,” she said. “What if I stood there and said 'Give me a hug?' ”

One student giggled, saying she did not like the idea.

“I've always seen a student-teacher relationship as more of a professional thing,” offered Michael Fayer, 13.

“Most of you were not comfortable giving me a hug,” Ms Marcoux said. “That's totally OK because you are responsible for your decisions about your body.”

In Montgomery County, Maryland, discussions about consent now begin as early as fifth and seventh grade, in addition to 10th grade, with the goal of exposing students to these basic topics before they become sexually active.

One Pew Research study found that 20% of teens ages 13-14 and 44% of those aged 15-17 reported that they'd had some type of romantic relationship or dating experience.

But how does a teacher talk about such a fraught subject with students in the midst of the hormone-crazed, anxiety-inducing middle school years?

Fayer, the 13-year-old boy in Ms Marcoux's health class, has no interest in dating, he said. His twin sister has been in relationships, which Michael said “lasted a couple days to a couple weeks,”

But he does not really see the need for it at this age. “I just don't want to deal with that until I'm older,” he said.

Neither does Addison Wetzel, a 13-year-old girl in the same class. She has been in a relationship once before, she said, when a boy in fifth grade told her he liked her.

Addison said she liked him back. They ultimately decided to just stay friends.

Her mother, Ms Beth Wetzel, said that while she supports the school's classes on consent, she does not want her daughter to have to worry about these topics quite yet.

“They're just getting their periods, they're just getting comfortable with making eye contact with a boy, let alone having any conversations,” Beth Wetzel said, adding that she has not had conversations about consent or sexual assault with her children, who are both in middle school.

On one occasion, they asked her why Matt Lauer was no longer hosting the Today Show, which they frequently watched together at home. Wetzel simply told them he was fired due to alleged inappropriate behavior at work.

“Maybe I did a disservice by not going into greater detail,” she said.

Back in Marcoux's health class, the teacher explained that to give consent, both parties must be of legal age, 16 or older in Maryland, and must not be intoxicated. Consent is ongoing and can be withdrawn at any time, she told them. When a hug lasts just a bit too long, for example, you can say, “OK, I'm done, I don't want to hug you anymore.”

She played a YouTube video showing a boy and a girl asking one another to hang out, to shoot basketball hoops, to play video games. At the end of the video, the boy asks the girl if she wants to kiss.

“How many of you thought 'Oh, but it ruins the moment?' ” she asked. The students chuckled, a few of them raising their hands.

“I think that no, it does not ruin the moment,” Ms Marcoux said, adding that it shows respect for the other person's boundaries.

On the second day of the two-day lesson on consent, Ms Marcoux showed students a photo of a football player, alongside a quote:

“I'm going to start tackling guys in football jerseys and saying, Look what he's wearing. He was asking for it.”

She asked them what this might have to do with consent. Michael raised his hand.

“You shouldn't tackle people in the middle of the street, just for wearing a shirt,” he said.

“Yes, but is there another situation that's very, very similar to this that actually happens in real life? Think about females being sexually assaulted,” Ms Marcoux asked.

“They are assuming just because he has a football jersey that he wants to be tackled,” one girl said.

“We cannot assume that somebody wants to do something because of what they're wearing, because maybe they were flirting, because they did it once before,”

Ms Marcoux told the class. “We cannot make these assumptions.”

This made sense to Michael, but other aspects of the topic were not as simple, he said later.

He thinks the #MeToo movement can be a “double-edged sword.” He believes it is important not to blame the victim, but he also worries about false accusations against boys and men, he said.

Growing up with a twin sister and two older sisters, he said he knows how it feels to be outnumbered and to be accused of things he did not do.

The class on consent has helped “clear some things up,” he said. If anything, it has made him realise how much he does not understand.

“It really helps make me realise that the world is a much bigger and more complex world than I know,” he said.

At the end of class, Ms Marcoux walked around the tables and encouraged everyone to submit a question into a box. She would answer the questions during a later class.

Michael thought back to what his teacher said about alcohol and consent. He scrawled a question on a blue note card: “Is something consensual or not consensual if both people are drunk?”

He really wasn't sure what the right answer might be.

As the bell rang for the end of class, he dropped the notecard in the teacher's box, packed up his things and walked into the hallway.

The Washington Post

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments