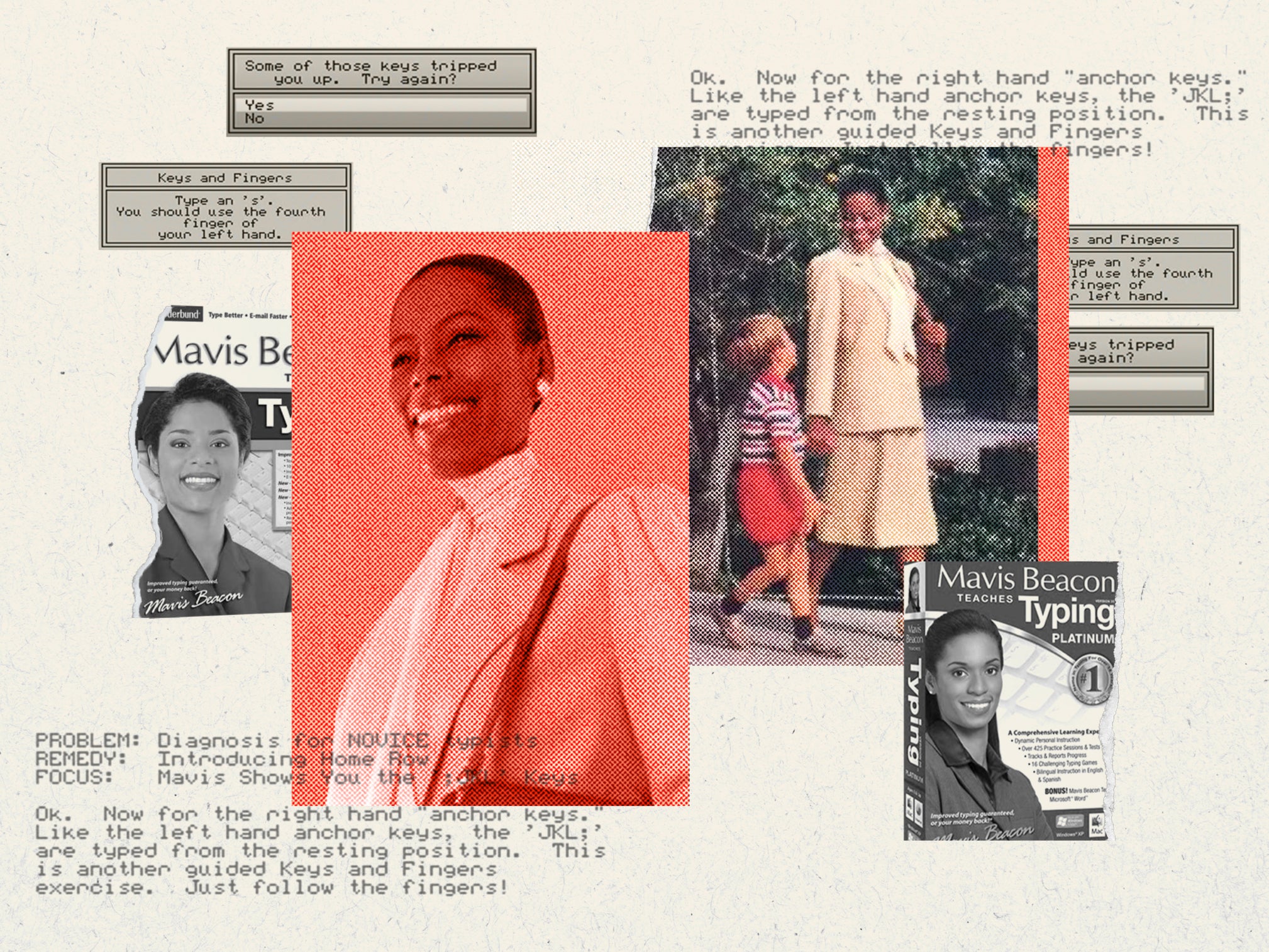

Mavis Beacon was the top typing teacher in the US before she vanished. The twist? She wasn’t real

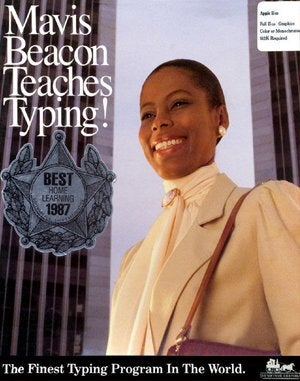

Mavis Beacon is the titular teacher in ‘Mavis Beacon Teaches Typing’, an educational program that became a bestseller after its launch in 1987. Clémence Michallon documents the making of an icon

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.A generation of adults learned how to type thanks to Mavis Beacon. Mavis Beacon Teaches Typing, an educational software program, launched in 1987 and quickly became a bestseller. To this day, adults who came of age in the Eighties and Nineties remember Mavis’s tutelage. Mavis comes up in fond remembrances on social media; she is frequently referenced when the subject of typing is broached. And, often, people are shocked to learn that the woman who taught them that skill – a figure they remember from their childhood, someone they, in some cases, came to admire – never existed.

Mavis Beacon was a made-up character, conjured up at an age when consumers were still learning how to interact with computers. Creating an avatar such as Mavis was a way of making the software more accessible, the interaction more natural.

Incarnating Mavis was a Haitian-born woman called Renee L’Esperance, spotted behind a cosmetics counter at Saks Fifth Avenue by one of the men behind the company that sold Mavis Beacon Teaches Typing. A new documentary, Seeking Mavis Beacon, will examine the character’s legacy and attempt to locate L’Esperance, who fell out of the public eye in the mid-Nineties.

Mavis Beacon Teaches Typing was a product of The Software Toolworks, a software and video game developer founded in 1980 in Sherman Oaks, California and now headquartered in Novato. The company had experimented with an anthropomorphic character for The Chessmaster 2000, the first computer chess game in the Chessmaster series. That program launched in 1986 with packaging featuring a bearded, long-haired, wizard-like character as the titular chessmaster – character actor Will Hare, according to a 2015 Vice article.

“We felt like if you could believe that you were playing another person, as opposed to a machine, that would make it much more engaging,” Joe Abrams, who later created the character of Mavis Beacon with his business partners Les Crane and Walt Bilofsky, told the publication.

It was Crane, a former late-night television host who turned to the software industry in the Eighties, who spotted L’Esperance at Saks Fifth Avenue in Beverly Hills. L’Esperance, “born into a well-to-do Haitian family”, had fled the regime of François Duvalier, according to a Software Toolworks file read by Bilofsky to The New York Times for a 1998 story. “She had never modelled, and her extremely long fingernails made her an unlikely typist, but when Les looked at her, he saw Mavis,” the file continues.

Abrams told Vice L’Esperance was paid a flat fee and posed for photos as Mavis over the course of one Sunday in Los Angeles’s business neighbourhood of Century City. Due to her long nails, a decision was made not to show her hands, Abrams said. (Olivia McKayla Ross, an investigator and associate producer on Seeking Mavis Beacon, told Mashable the narrative on the exact length of L’Esperance’s nails has fluctuated.)

Mavis Beacon was made up, but to many people, she felt real. Adrienne Hankin, public relations director for Mindscape, a software company purchased in 1990 by The Software Toolworks, told The New York Times in 1998 – 11 years after the launch of the original Mavis Beacon Teaches Typing – that she got “a couple of calls a week” inquiring about booking Mavis for speaking engagements. “A lot of reporters will call and ask for interviews,” Hankin said. “Teachers call in and want to know more about Mavis and where she’s teaching these days.” Consumers, too, got in touch to find out more about the woman they believed to be a typing expert.

“’The reaction [for people finding out Mavis wasn’t real] is shock,” Hankin told the newspaper. “People seem to think she’s a real teacher. And she is. She’s just real on a computer screen.”

The belief that Mavis Beacon was a real person seemed to extend to the software industry itself. “I remember, at [computer trade show] Comdex in 1987, walking around and having some of the competitors from two of the original typing products come up to me and say: ‘What a coup! How did you get Mavis Beacon to endorse your product? We’ve been after her endorsement for years,’” Abrams told The New York Times. “And when they did that, I knew we had a hit.”

Mavis wasn’t just a face on the packaging. As a character, she was integrated to the Mavis Beacon Teaching Typing gameplay. Videos of the software at work show how users would be told that “Mavis” would show them a specific set of keys, or instructed to “introduce yourself to Mavis” in the early stages.

Having a Black woman held up as a model of excellence and expertise mattered. Some retailers, Abrams told The New York Times, displayed “some initial reluctance to carry the product because there was a Black woman on the box” and “people did not believe it would sell”. Abrams told Mashable he and his partners were “proud” to have L’Esperance as the face of their software, and that they are glad that Mavis Beacon later became a role model of sorts for Black children at a time when representation was scarce – although they didn’t necessarily set out to create such a role model. Hankin told The New York Times that hiring a Black woman for the role wasn’t “intentional”, and that “Les [Crane] was just looking for who the right person would be to play Mavis”. The decision, Bilofsky told Mashable, simply didn’t seem that controversial to “three Jewish guys from the Bronx”.

Seeking Mavis Beacon will examine the idea of “intention versus impact”, Jazmin Jones, the documentary’s lead investigator and director told Mashable, adding: “I don’t really question that Mavis Beacon was made with the best of intentions that can happen under capitalism.”

In November 1987, Mavis Beacon Teaches Typing received a rave review in The New York Times. “Of the many good typing programs available, Mavis is the best we’ve seen,” reviewer Peter H Lewish wrote, making note early on of Mavis’s fictional identity. “I don’t know how they teach typing elsewhere in the world, but I do know that Mavis is light years ahead of my high school typing commandant.”

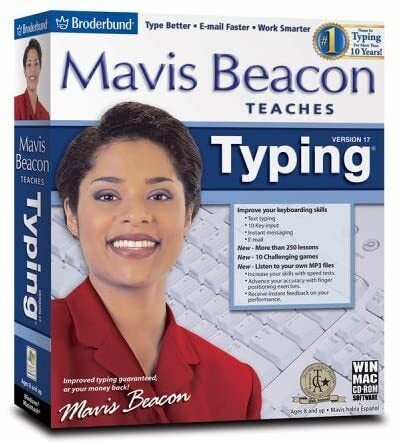

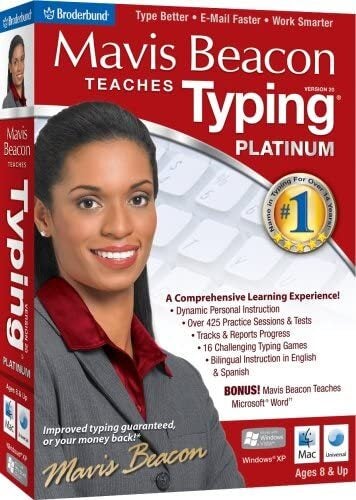

The phones at Software Toolworks, Abrams told the newspaper, were soon ringing “off the hooks”. Mavis Beacon Teaches Typing sold 6 million copies over the next 11 years. Other models eventually replaced L’Esperance on the product’s packaging. The software itself remains for sale in a download format; older iterations are still available on hard copy.

Little is known about L’Esperance and her life and career. “We had some occasional contact with her through 1990, and she was thrilled about the success, and started to be recognised,” Abrams told Vice in 2015. He and L’Esperance lost touch after The Software Toolworks moved from Los Angeles to San Francisco in 1990. A 1995 story in The Seattle Times said L’Esperance was living “quietly in the Caribbean”. This is the last known update as to her whereabouts and wellbeing.

The team behind Seeking Mavis Beacon has asked for any leads and tips about L’Esperance or any of the other models who later incarnated Mavis. “We don’t know what we’re going to find,” Jones told Mashable. “And we hope that it is a triumphant story in which Renee L’Esperance is just chilling, and is like, ‘Why did you bother me? I’m living great.’” The documentarians are also interested in hearing from people with strong memories associated with the character and the typing software. A website has been set up, as well as a hotline for people looking to share information.

This article was amended on 24 March 2022. It previously said The Software Toolworks was founded in 1990, but it was founded in 1980.