Secret US drone whistleblowers say operators 'stressed and often abuse drugs and alcohol' in rare insight into programme

Four men have come forward to provide an unprecedented glimpse inside the US drone programme

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.America’s drone programme is unregulated, counter-effective and carried out by stressed men who often abuse drugs and alcohol, according to some of the people who spent years remotely flying the missions.

In an unprecedented insight into the inner workings of the CIA-controlled programme that is as secretive as it is controversial, four former operators have told of their concerns that innocent civilians were routinely killed and yet chalked up as “enemy combatants”.

For a number of years, the whistleblowers played an integral role in a programme that was started by President George Bush as part of the so-called war on terror and greatly expanded by Barack Obama.

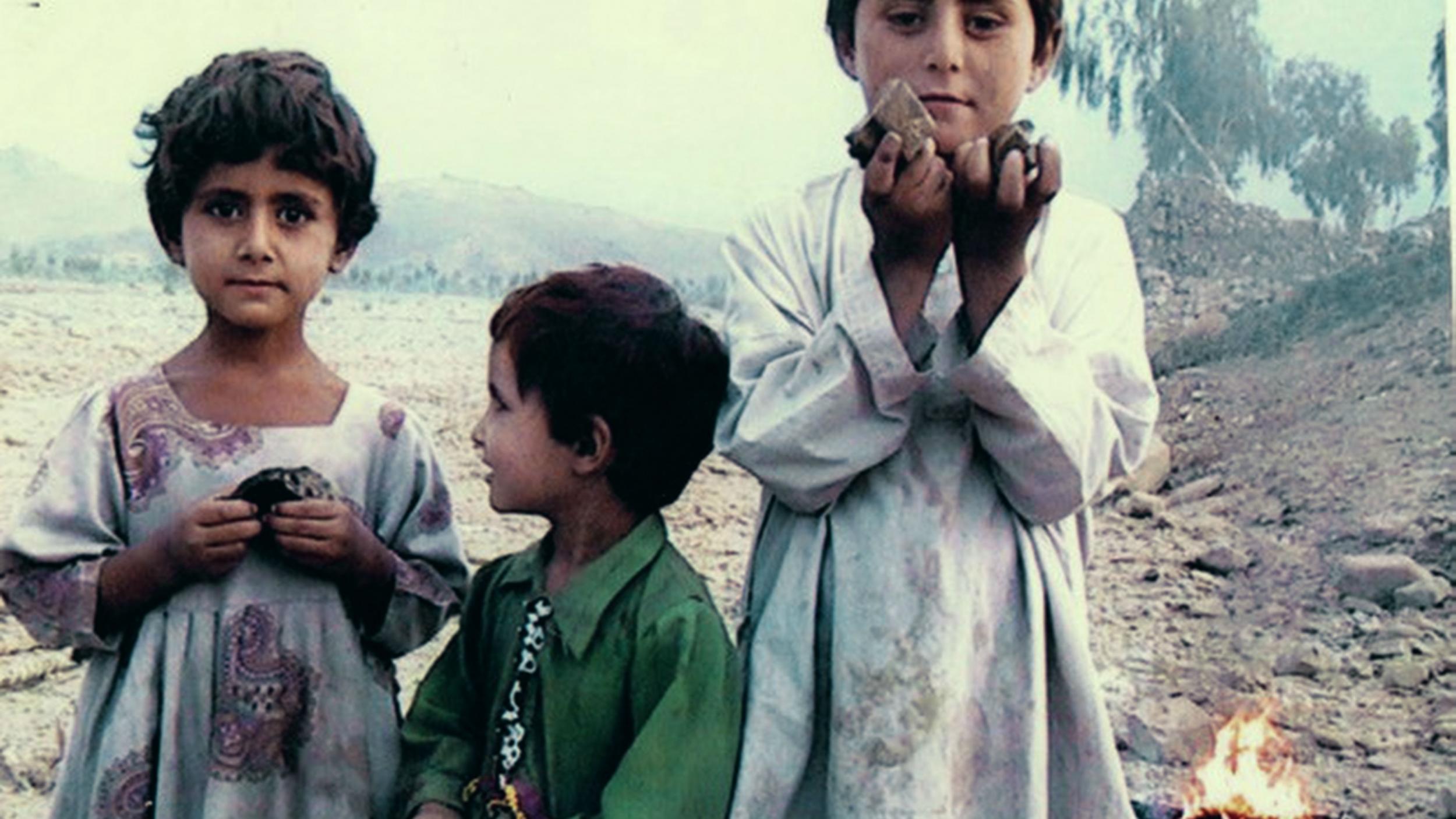

From as far as 8,000 miles away in their base in the Nevada desert, the men operated unmanned drones carrying Hellfire missiles, in places such as Afghanistan, Pakistan, Iraq and Yemen.

Yet the men questioned both the utility of the programme and suggested it may actually create more militants than it kills. The strikes are also hugely controversial in the countries where they are carried out.

The operators - who feature in Tonje Hessen Schei’s documentary Drone - said they were encouraged to dehumanise their targets and even referred to the children they monitored with their drones as “tits”, or “terrorists in training”, or “fun-sized terrorists". The four said they had struggled with depression and even suicidal thoughts since quitting.

“When you were not actually firing a Hellfire missile, the job is pretty boring,” said former drone pilot and instructor Michael Haas, who served with the 15th reconnaissance squadron and 3rd special operations squadron from 2005 to 2011 and worked out of Creech Air Force base near Las Vegas.

“Alcoholism was not considered to be a problem. Every night we would get off our shift and we’d drive into Las Vegas and drink for three or four hours. I also had a cocaine problem…I’d take little bumps of bath salts and then go and instruct a ride. Synthetic cannabis.

“I’d have a bottle of Jack Daniels in my flight bag and I’d swig it walking back to my room. Anything you could do to bend that reality and picture yourself not there.”

Casualty estimates from the Bureau of Investigative Journalism put the number of deaths from drone strikes in Pakistan between 2,489 and 3,989. Strikes in Afghanistan are estimated to have killed between 700 and 1,046.

Another operator, former airman Cian Westmoreland, said he had been told he had been responsible for “204 enemy kills”.

“That is BS. Not all the ‘enemies’ were enemies,” said Mr Westmoreland, who worked out of Afghanistan’s Kandahar air base.

Mr Westmoreland said he had suffered from depression since quitting his job and currently took five different medications to control anxiety and mood swings.

He said that a month ago he was standing on the Rio Grande Gorge Bridge in Taos, New Mexico and “was going to jump”.

“I thought about my sister and the person who is now my fiancé. I went to the VA (Veterans Affairs administration) and they put me in a psych ward for five days. I’ve not received any benefits.”

The men, who spoke in New York a day before the release of Ms Schei’s film, also provided an insight into the questionable precision of the selection process for targets.

The operators said they were supposed to combine signals intelligence, imagery and human intelligence. Often they lacked one or more of these and yet they still proceeded with the kill missions.

Brandon Bryant, a former special operations Staff Sgt, said he had carried out five different kill missions. One of them involved a missile fired at a group of men who he had tracked crossing into Pakistan from Afghanistan. He had been told the men were carrying explosives that were to be passed on to other militants.

“We waited for them to go to sleep and then we killed them,” he said. Mr Bryant said he saw no secondary explosion after the missile struck, suggesting they had not in fact been carrying munitions.

Mr Bryant, 30 and shaven-headed, said he had also been part of the operation to track and kill Anwar al-Awlaki, the US citizen and Muslim cleric was accused by the US of acting as a radical in Yemen and planning operations for al-Qaeda.

He was killed by a drone strike in September 2011, the first American citizen to suffer that fate and triggering a debate about whether Mr Obama had the legal right to assassinate a US citizen without due process. His 16-year-old son, Abdulrahman Anwar al-Awlaki, was killed in another drone strike two weeks later.

Mr Bryant claimed some members of the team were unhappy about the operation to target al-Awlaki, given that he was an American citizen.

“People were saying they had sworn an oath to defend the Constitution and that even a traitor deserves a fair trial,” he said.

Another whistleblower, former airman Stephen Lewis, said he had struggled to his retain his sense of humanity after giving up his job as a drone operator.

“You come back from deployment and you’re fine. Then something happens and you fly off the deep end. It huts you, it’s hell. It’s the worst feeling on the planet,” he said.

“The programme hemorrhages people. We don’t like it. It’s not a good job.”

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments