Sarah Palin 'cost John McCain two million votes in 2008 US election'

'Palin saw a sharp increase in negative evaluations as the fall campaign progressed'

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Sarah Palin's track record in politics from 2009-on isn't terrible. In the Tea Party wave of 2010, when Palin's popularity among conservatives was near its peak, candidates won in 33 of 64 races where she endorsed. She's had some high-profile wins since and some big losses, including on Donald Trump's current national spokesperson's congressional bid. The value of any one endorsement is often hard to determine, given the number of factors that go into a political campaign, of course.

There was one race in which Palin appears not to have been much help — and, in fact, hurt the candidate. According to a 2010 study from researchers at Stanford University, noted by Brendan Nyhan, Palin's presence on the 2008 Republican presidential ticket cost John McCain 1.6 percentage points. In an election in which 131 million people voted, that's 2.1 million votes that McCain should have gotten but didn't.

The researchers set out to determine the extent to which voters made up their minds on presidential candidates or on the performance of the party that was currently in office. To answer that question, they tried to figure out how much of an influence the candidates in the election had on moving support one direction or the other.

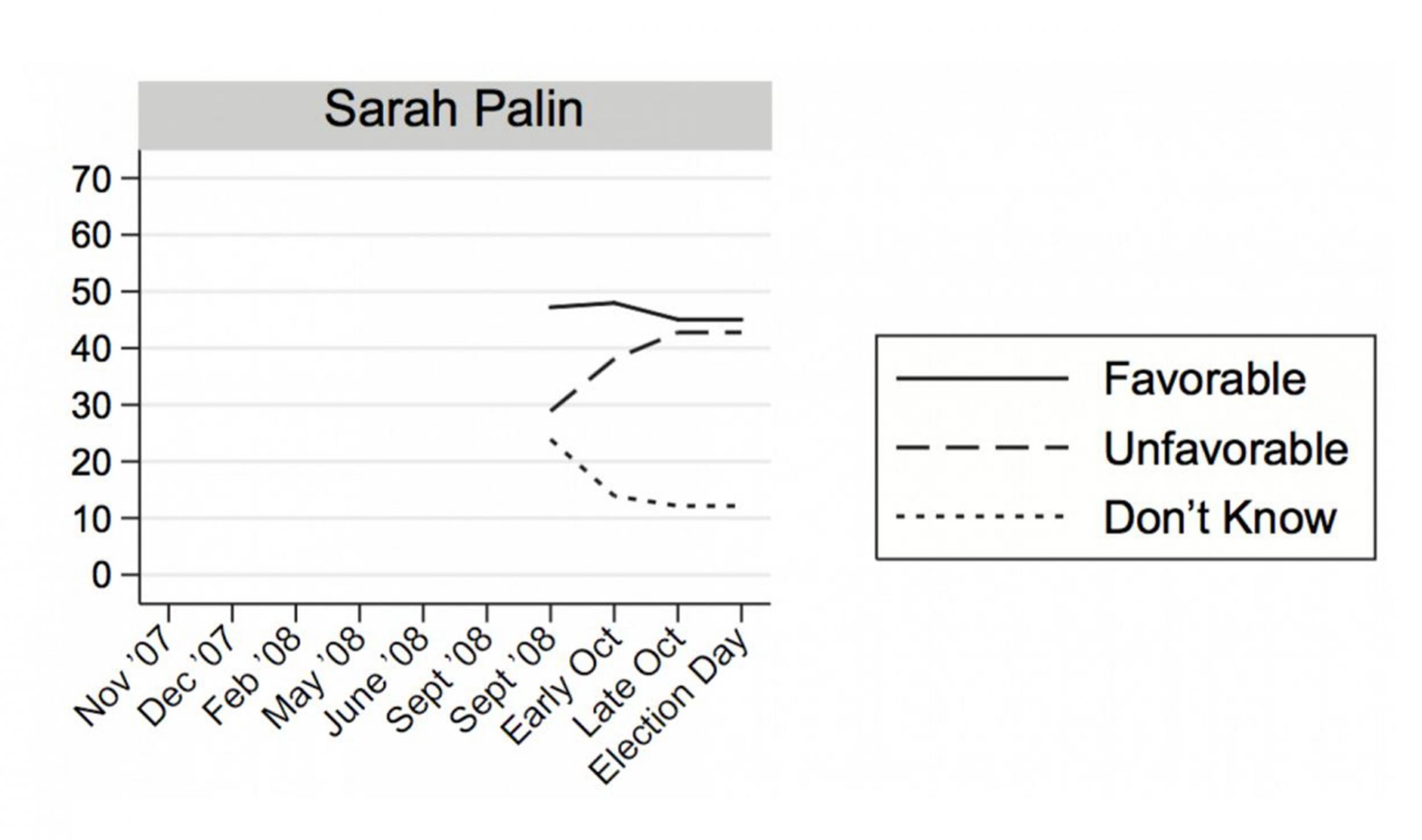

Part of that process was to look at how candidate favorability ratings changed over the course of the campaign. Below is the chart they created to show Palin's favorability, from the moment she was announced as the vice presidential pick (and introduced to most Americans) to election day.

As the campaign progressed, fewer people said they didn't have an opinion on Palin. And as nearly all of those people formed an opinion on her, that opinion was a negative one. As the researchers put it, “Palin saw a sharp increase in negative evaluations as the fall campaign progressed. Looking at individual-level changes in favorability, we find that 34% of respondents downgraded their evaluations of Palin between September and Election Day, while just 12% became more favorable.”

To figure out the role that shift played, the researchers modeled elections in which Palin's favorability didn't plummet in the way that it did. The result? What they call the “Palin effect.”

This counterfactual simulation finds that Palin’s declining favorability cost McCain 1.6 percentage points on Election Day. Since Obama actually won 53% of the popular vote, it suggests that Palin’s campaign performance did not necessarily change the election outcome, but was certainly large enough to be substantively meaningful.

We're looking at this now in light of Palin's endorsement of Donald Trump, of course, but it's important to set the context properly. We're not suggesting that this study means that Palin will have a deleterious effect on Trump in the primaries. On the contrary, Palin's endorsement likely helps solidify some support for Trump among conservative voters.

Instead, it's worth considering what happened with Palin in light of Trump's candidacy.

The study notes a 2008 Newsweek column which suggested that Palin “sent wavering Democrats, independents and moderate Republicans scurrying to Sen. Barack Obama.” In a CNN/ORC poll released that November, Palin's net favorability among independents was plus-8 — 47 percent viewing her favorably and 39 percent not. Obama's net favorability among independents was +54, Joe Biden's was +47 and McCain's was +31. In other words, the idea that independents were pushed to Obama (as stated in the column) is reinforced by the idea that people who looked at Palin negatively were less likely to vote for McCain — and independents looked at her more negatively than any other candidate.

If Trump wins the Republican nomination, there are conflicting theories about how voters react in the general election. Trump argues that he will turn out scads of new voters excited about his candidacy. (As we've noted before, if he wins the nomination, it's likely because he's proven he can do that.) Trump's opponents suggest that he will instead push moderate Republicans and independents away, given his unorthodox views. In other words, that he might experience a Palin effect of his own.

Palin and Trump are unusual candidates who've mixed up a generally predictable system. In 2008, though, the predictions were right: The Democrat won by about the margin that candidate-independent models predicted.

Copyright: Washington Post

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments