Rio de Janeiro citizens to receive new app to record police violence in city's favelas

Frightened citizens will be able to use a new app to report assaults and killings by officers

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

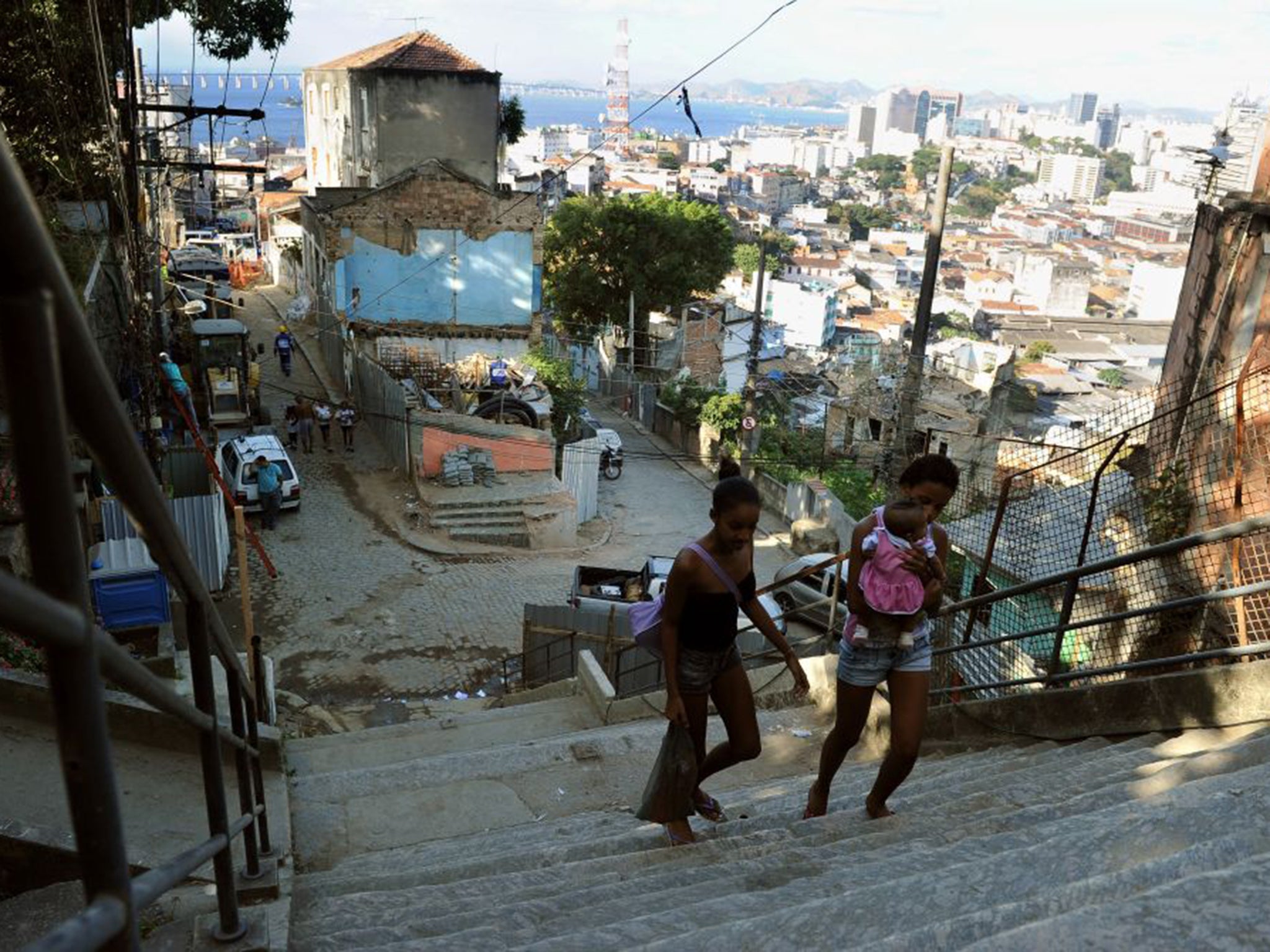

Your support makes all the difference.A palpable sense of fear pervades Morro da Providencia – the oldest favela in Rio de Janeiro – on the morning after a night of intense gunfire between local criminals and police.

For three hours, hundreds of bullets ripped through the public square of Praca Americo Brum on that recent night, in a location known as Coracao (Heart) at the top of the hillside Providencia.

It is where a local resident, Cosme Vinicius Felippsen, sits to explain how a new mobile app, being launched this month, will be used to report violence in Rio’s favelas.

Although no one was injured in the barrage, the favela itself, in central Rio, feels wounded and frightened. Mr Felippsen points out evidence of the fierce gun battle. Bullet holes pockmark the towering concrete pillars that form part of the structure of the nearby cable car lift, which was opened in 2014.

“It’s these types of incidents that residents will be able to record and report with our new app to show the sort of conditions we live under,” Mr Felippsen said. He is part of Forum de Juventudes (FJRJ) – Rio de Janeiro’s Youth Forum, the group responsible for developing the smartphone app Nos por Nos (Us by Us).

“It’s a self-defence tool for people to report violence, assaults and killings, particularly by the police. They can send videos, texts, record witness statements and post pictures, and these will be forwarded to human right bodies like Amnesty International, government public security organisations and the media that can take official action,” explained the 26-year-old, who works part time as a favela tourist guide and street salesman.

FJRJ members will monitor information, ensuring it is authenticated and that all complaints are followed up.

For Alex Azevedo, 24, who lives in Complexo do Alemao favela, about a 30-minute drive from Providencia, the application is welcome news. He believes that it would have helped him to report an alleged case of police brutality a month ago.

He said indignantly: “The police beat me in an alleyway for no apparent reason. I thought I was going to die. A woman on her way to church, who knew me, called my aunt who came and vouched for who I was. I am not a criminal.”

Users of the new app can upload complaints anonymously and access advice and information about their rights as well as draw on a community support network in times of emergency.

The idea for the app emerged after FJRJ carried out research analysing the impact of the city’s Pacifying Police Units (Unidade de Policia Pacificadora) on the lives of young people living in 11 of Rio’s 763 shanty-town communities, home to more than two million inhabitants. The first UPP was created in 2008.

The overriding complaint from those living on the periphery was the escalation in violence following the installation of UPPs, whose primary purpose is to reclaim territory from the control of armed gangs of drug dealers.

Rio has 38 favela-based pacification units, with the UPPs being an important part of the city’s strategy to ensure the safety of visitors for the Olympic Games later this year.

The most affected by any escalation are poor, black and mixed-race youths aged between 15 and 29, say human rights groups. According to data published last month by Rio’s Institute of Public Security – Instituto de Seguranca Publica (ISP) – of the 644 people killed in violent clashes with police in 2015 across the state of Rio de Janeiro, 497 (77 per cent) were black or mixed race.

Mr Felippsen has personal experience of the violence in the favelas – his 17-year-old brother, Paulo, was killed in 2010.

“He was on a motorbike with his friend when police opened fire,” recalled Mr Felippsen. “His friend escaped but my brother was injured and alive. By the time police took him to hospital he was dead. They claimed he was selling drugs but there has never been an inquiry.”

The issue of police violence is clearly on the minds of many in Providencia. Electrical engineer Iuri Velosa Santos, 23, complained: “The police use force as an excuse to intimidate and humiliate us.” He says he was punched in the head by an officer after being wrongly accused of not paying his bus fare while on his way to work three weeks ago.

“But we are making them more accountable because our mobile phones are becoming our weapon of choice in our battle for justice,” Mr Santos said.

In a survey last year, Sao Paulo research body Data Popular reported that slum dwellers are “vigorous” users of social media, with the majority using mobile phones with free Wi-Fi connection. The data showed that 74 per cent of hillside residents in Rio access the internet at least once a week, compared with 54 per cent of those living in wealthier neighbourhoods on lower ground.

Mr Felippsen said: “The Us by Us app is one more thing to help in our fight against police violence. We need to tackle institutionalised racism in our police force and change the attitude of officers who believe slum dwellers’ lives don’t matter.”

Carlos Henrique’s 16-year-old son, Carlos Eduardo, died with four friends when their car came under a hail of more than 100 bullets fired by police in November last year.

The five youngsters, all black, and aged 16 to 25, were out celebrating their first pay packet in Costa Barros, a suburb in Rio.

“My son was an innocent, loving and studious boy who was planning to join the navy,” said a grief-stricken Mr Henrique. “Witnesses said they raised their arms and shouted they were locals. The police are meant to be our protectors but we live in fear every day of being on the end of excessive force at their hands.”

The officers involved claimed the exaggerated use of ammunition was an act of self-defence as the car had been used in a robbery. Investigators confirmed that none of the boys had a criminal record and that no shots came from inside the car.

In a statement, Jose Mariano Beltrame, Rio’s security secretary, described the incident as “indefensible … unnecessary and exaggerated”, and promised a thorough investigation. He denied police gun-handling training was inadequate and added that a new investigative unit had been set up to help “reduce the level of criminal incidence by the police”.

Four officers have been arrested and are awaiting trial for murder.

Even so, Mr Felippsen warned: “There’s every chance they could get off. We have no faith in the criminal justice system. But if we sit back and do nothing ... the injustice in our lives will never end. Using modern technology is the smartest way forward to fight back.”

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments