Rhodri Marsden's Interesting Objects: The presidential hotline

The need for a hotline became apparent during the Cuban Missile Crisis when laborious translation procedures caused diplomatic difficulties

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

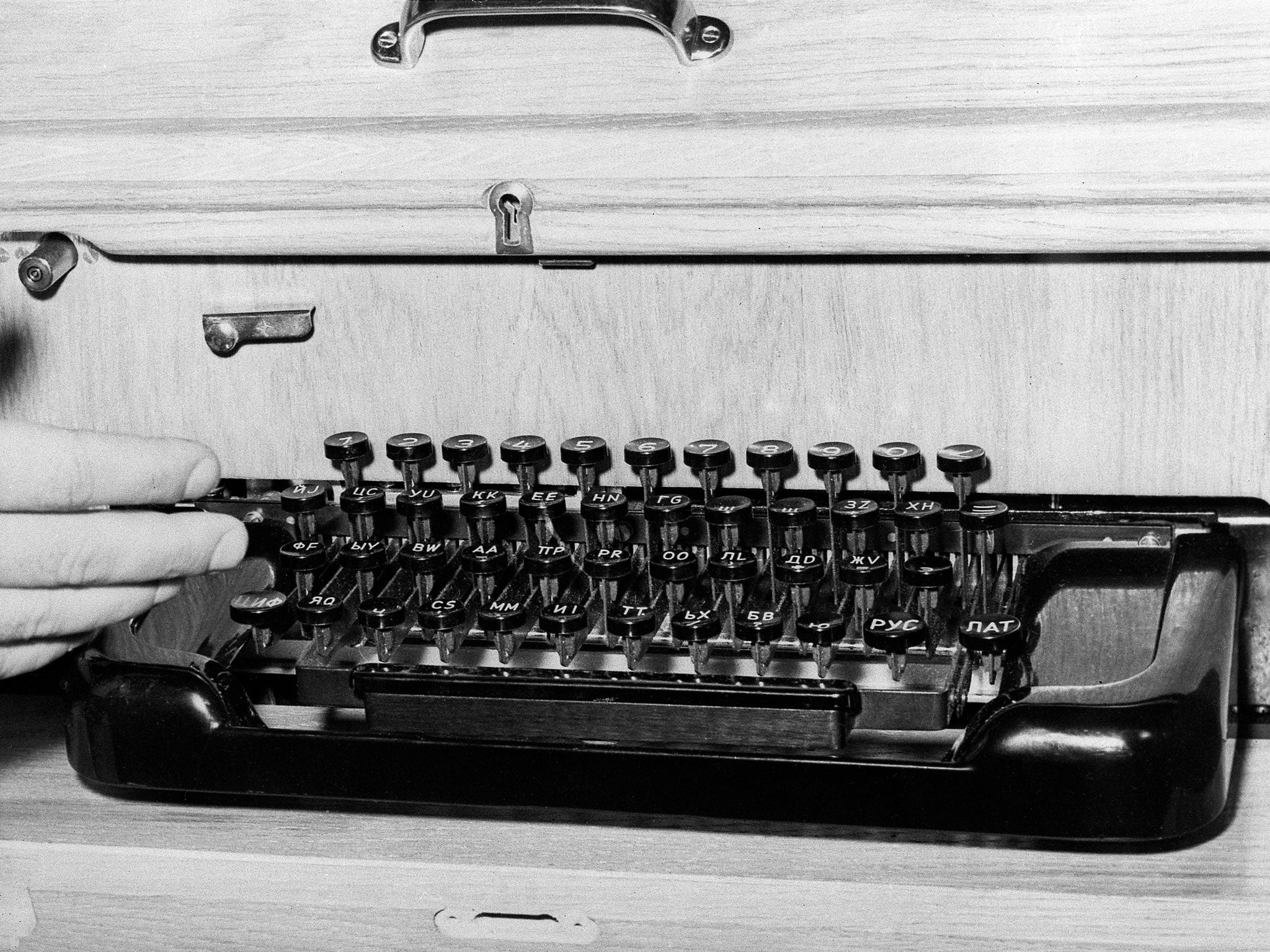

Your support makes all the difference.At the Jimmy Carter Library and Museum in Atlanta, Georgia, there's a phone on display with no dial. "The red phone was a hotline to the Kremlin in Moscow," says the accompanying sign. "A US president could pick up the phone and speak directly to Soviet leaders in times of crisis." But the hotline, installed this weekend in 1963, never used telephones, red or otherwise. A Siemens T-63 SU12 teleprinter was used in Washington to receive messages in cyrillic, while Moscow took delivery of a Teletype 28 ASR. The first message it received from America: "The quick brown fox jumps over the lazy dog's back 1234567890."

The need for a hotline became apparent during the Cuban Missile Crisis when laborious translation procedures caused diplomatic difficulties. A direct connection, as envisaged in Peter George's 1958 novel Red Alert (later made into the film Dr Strangelove), might just prevent the accidental triggering of nuclear war. "Weapons control and guidance systems," warned the Russian minister of foreign affairs, Andrei Gromyko, "are becoming more and more independent of the people who create them." But a telephone link wasn't viable. Encryption techniques were too limited and the potential for misunderstanding too great.

The wire link was only used sporadically, but was regularly tested with baseball scores or excerpts from Chekhov. The first critical communication from Russia came during the 1967 Six-Day War in the Middle East. That printed message had to be relayed from the Pentagon to President Johnson via a pneumatic tube, and at that point the decision was made to actually extend the wire to the White House. Fax and email would eventually replace the wire, but the red phone was only ever symbolic. The curator of the Jimmy Carter Museum admitted in 2013 that it "was just a prop that the exhibition designer wanted to use."

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments