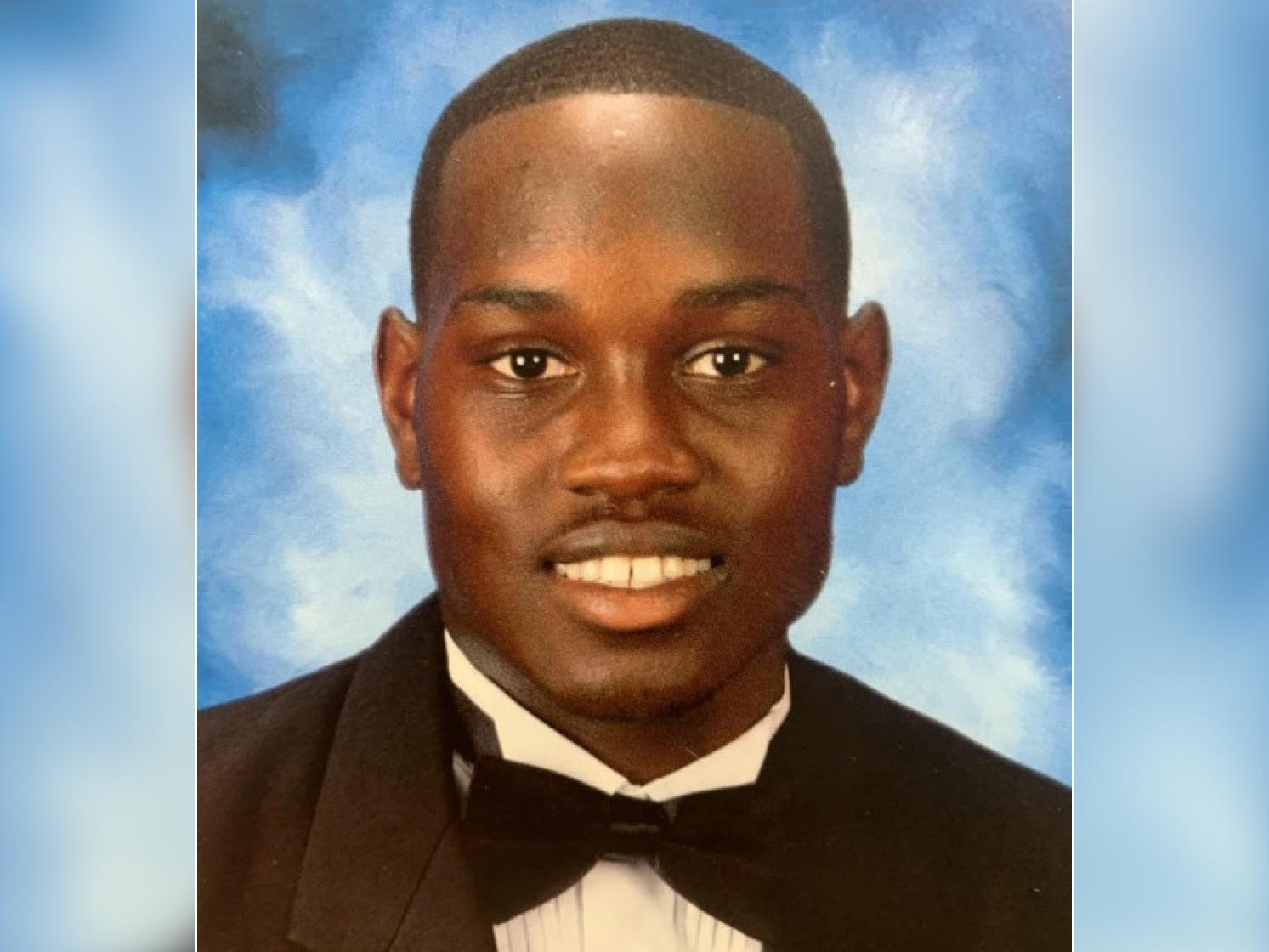

A ‘modern-day lynching’ or ‘citizen’s arrest’?: How race is central to the trial of Ahmaud Arbery’s killers

Opening arguments begin Friday in the trial of the three White men accused of murdering Black 25-year-old Ahmaud Arbery, writes Rachel Sharp

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.The family of the Black man killed call it a “modern-day lynching”.

The attorneys for the White men accused of his murder say it was a “citizen’s arrest”.

Now, 21 months after 25-year-old Ahmaud Arbery was shot dead in a street in New Brunswick, Georgia, a jury of 11 White people and just one Black person will decide.

“There is no question that race is a central part of this case and has been from the very beginning,” Brandon Buskey, director of the ACLU’s Criminal Law Reform Project, tells The Independent.

“If Ahmaud Arbery had been a white person in the same circumstances he would still be alive today and that’s a sad fact of our nation’s history.”

It was the afternoon of 23 February 2020 when an unarmed Mr Arbery was jogging through the sleepy waterfront neighbourhood of Satilla Shores.

Residents Gregory McMichael and his son Travis McMichael jumped in their pickup truck armed with a pistol and a shotgun and chased him.

Their neighbour William “Roddie” Bryan Jr joined the father and son team in the pursuit in his own truck, while filming the encounter on his smartphone.

The McMichaels tried to corner Mr Arbery with their truck before a tussle broke out between him and Travis.

Travis opened fire and shot the Black man three times.

Mr Arbery ran a few steps further from 35-year-old Travis before he collapsed to the ground and died.

A post-mortem revealed he had been shot twice in the chest and once on the inside of one of his wrists.

As Travis stood over Mr Arbery’s body while he bled out in the street, he called him a “f***ing n****r”, Mr Bryan told investigators.

The McMichaels said they chased Mr Arbery down to carry out a citizen’s arrest because they suspected him of burglary.

Travis claimed he then shot Mr Arbery in self-defense.

Gregory told officers he had a “gut feeling” that the Black man was responsible for a series of recent break-ins in the area.

Glynn County Police records show there had been no reports of alleged break-ins in the area in the seven weeks prior to Mr Arbery’s death.

Mr Arbery was also unarmed and he was not considered a suspect in any burglaries.

A racially motivated killing?

The defense for the three men insist that what happened that day - three white men chasing and shooting dead a black man while he was out for a jog - was not racially motivated and that race plays no part in the case.

The prosecution, meanwhile, argues that it does and have asked to present evidence of the alleged histories of racism of each of the three men.

At bond hearings last year, prosecutors revealed Travis had used racist language in multiple social media posts and text messages.

In one November 2019 message, he texted a friend about “shooting a crackhead c**n with gold teeth with a Hi-Point .45”, prosecutors said.

In another, he allegedly used an offensive racial slur to refer to Asian people.

He is also said to have shared a number of “racial” social media posts online.

His 67-year-old father, meanwhile, reportedly shared a number of “racial” Facebook posts while 52-year-old Mr Bryan repeatedly used the “n-word” in text messages, prosecutors said.

Last month, attorneys for the McMichaels tried - unsuccessfully - to ask the judge to ban images of a license plate on Travis’ pickup truck which featured the Confederate flag.

The McMichaels argued it would be "prejudicial" to the jury, but the judge ruled that jurors can interpret it "in any way they deem appropriate".

While jurors will only be tasked with deciding the guilt of the three men on trial, the backstory of the case has raised wider questions around whether institutional racism in the local criminal justice system protected the defendants from being brought to justice.

“Why would he be in cuffs?”

For three months after the killing, none of the men were arrested or charged.

Bodycam footage taken from officers arriving on the scene shows how the first cop to arrive failed to give Mr Arbery medical aid, instead stopping to speak to the suspects.

In the footage, Mr Arbery is clearly still alive, moving his head and leg as he lay dying on the ground. A second officer then arrived and pronounced him dead.

The McMichaels and Mr Bryan were not taken into custody and the cops showed no skepticism around their version of events, deciding then and there that it was “self-defense”.

At one point, one officer even said of Travis: “Why would he be in cuffs?”

It was only after the video was leaked online in May 2020, prompting national outrage over both Mr Arbery’s killing and why the suspects were walking free, that the Georgia Bureau of Investigation took over and opened an investigation.

Days later, the McMichaels were arrested and charged with felony murder and aggravated assault.

Mr Bryan, who initially claimed he was an innocent bystander, was arrested and charged with felony murder and criminal attempt to commit false imprisonment two weeks later.

Mr Bryan struck Mr Arbery with his truck after joining his neighbours in “hot pursuit” of the Black man, a Georgia Bureau of Investigation agent later testified.

Sheryll Cashin, Carmack Waterhouse Professor of Law, Civil Rights and Social Justice of Georgetown University Law Center and author of White Space, Black Hood: Opportunity Hoarding and Segregation in the Age of Inequality, says she believes “race had everything to do with [charges not being brought at the time]”.

“Charges only came about when the video was released and it caused a statewide and national outrage,” she tells The Independent.

“You see evidence of complicity in a system that privileges policing and vigilantism when it comes to black people.

“If the circumstances were reversed and three black men were chasing down a young white man and shooting him they would have been treated differently.”

Gregory was also well-connected to senior figures in the local criminal justice system.

He was a retired Glynn County police officer and had also worked as an investigator in the Glynn County District Attorney’s office for 24 years.

Many believe that, from the moment Mr Arbery was killed, his position and the three men’s races protected them from prosecution.

The first prosecutor assigned to the case, Brunswick Judicial Circuit District Attorney Jackie Johnson, recused herself due to Gregory’s position as a former investigator in her office.

In September of this year, she was criminally charged with misconduct over her handling of the case.

She is accused of using her position to shield Mr Arbery’s killers from prosecution.

The second prosecutor George Barnhill recused himself around two months after the killing in April for conflict of interest after learning that his son had worked with Gregory on a previous prosecution of Mr Arbery.

But, days before his recusal, he sent a letter to police saying the actions of the three men were “perfectly legal”. He had given a similar opinion one day after the shooting - even before he was assigned the case.

Mr Barnhill had a history of controversial prosecutions of black people in the area.

A civil war-era law

At the time of Mr Arbery’s death, Georgia still had a citizen’s arrest law in place and the defense plans to argue the defendants acted within this law.

Under the law, private citizens had the power to detain someone if they suspected them of committing a serious crime and if the suspect was trying to escape.

The state law dates back to the American Civil War era and is rooted in the state’s slave trade past.

Ms Cashin says that the citizen’s arrest law gave “privileges to and encouraged the policing and the shooting of black people.”

“We have a history of surveillance of black bodies from slavery and we have laws that authorize the surveillance of black bodies,” she says.

“We have a long history of encouraging non-black citizens to police black bodies and that civil war-era law was about conscripting the average white person into catching escaped, enslaved black people.”

While the law was repealed in February in the wake of Mr Arbery’s killing, Ms Cashin says the state - and many US states - still have other laws in place that similarly encourage “vigilantism”.

For example, three in four US states - including Georgia - still have a Stand Your Ground law in place.

Parallels have been drawn between Mr Arbery’s killing case and the killing of Trayvon Martin, a 17-year-old black teenager who was shot dead by George Zimmerman, a white neighbourhood watch captain in Florida in 2012.

Mr Zimmerman was acquitted on the Stand Your Ground law, which allows people to use guns and other deadly force in self-defense without first trying to retreat.

Ms Cashin says that where a shooter is white and victim is black, the shooting is 10 times more likely to be justified under the statute than if the victim is white.

While Georgia had these laws in place at the time of Mr Arbery’s killing, the state was one of only four states that did not have a hate crime statute.

This meant that, even when felony murder charges were finally brought against the McMichaels and Mr Bryan, no hate crime charges were filed. Hate crime legislation has since been passed into law in Georgia in the wake of Mr Arbery’s death.

However, this April, the Department of Justice brought federal hate crime charges against the three suspects.

The DOJ specifically said that the McMichaels and Mr Bryan had "used force and threats of force to intimidate and interfere with Arbery’s right to use a public street because of his race”.

Their federal trial is scheduled to begin in February.

Jury: 11 White, one Black

With jurors in the state trial told to report Friday morning for the opening statements, race is already front and center.

On Wednesday, the court announced that jury selection had finally been completed after a challenging two-and-a-half weeks.

Race featured heavily in the questions put to jurors, with the prosecution and defense disagreeing over what should be asked.

In the end, potential jurors were asked their views on topics including Black Lives Matter and the old state flag which features the Confederate flag.

The process saw some potential jurors say they already had strong opinions about the case, others say they were concerned about the impact their decision would have on the community - and others were simply no-shows.

The result: on a jury of 12, 11 people are white and one is black.

In Glynn County, where the trial is taking place, more than 26 per cent of the population are Black and 69 per cent are white, according to 2019 Census data.

Black people had made up a quarter of juror finalists, with 12 Black and 36 White left in the pool - which would have correlated with the racial demographics in the county.

But, the defense then used 11 of their allotted peremptory strikes on Black potential jurors in a move that the prosecution has called an act of “racial discrimination”.

The prosecution filed a reverse Batson challenge on Wednesday accusing the defense of deliberately striking black jurors when they were qualified due to their race.

The Batson challenge is traditionally used to argue that prosecutors are stacking a jury with White people against a Black defendant.

In this case, the prosecution argued the defense was stacking a jury with White people where the victim was Black.

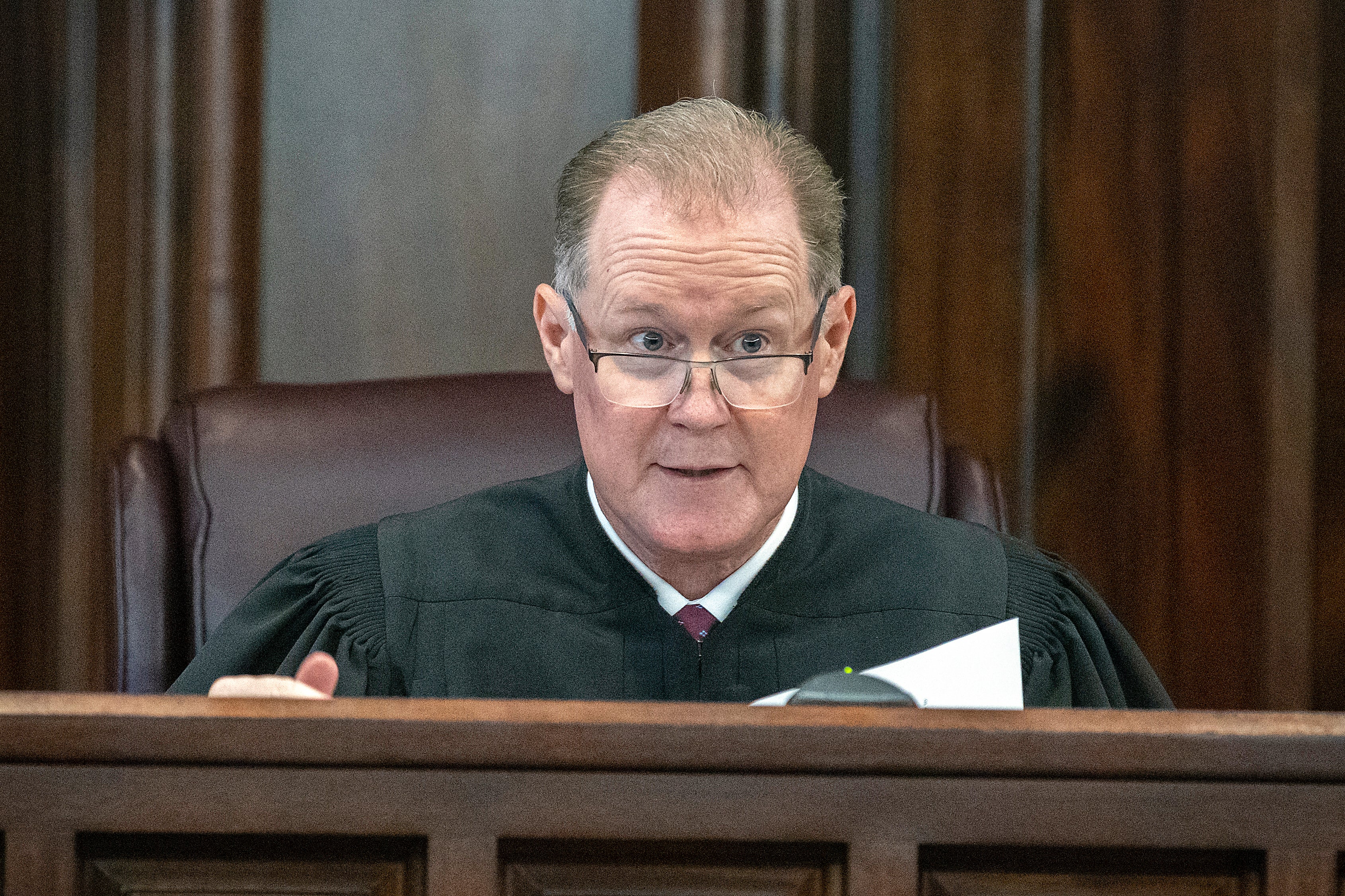

Judge Timothy Walmsley agreed with the prosecution, saying there was “intentional discrimination” by the defense.

But, he allowed the case to move forward with the almost all-White jury anyway, saying the defense had shown other valid reasons beyond race for striking the jurors.

"One of the challenges that I think counsel recognized in this case is the racial overtones in the case… This is sort of the continuation of a conversation that I think will continue for a long time, with respect to this case," he said.

Perhaps ironically, the lack of diversity in the jury came after the defense previously raised concerns of a lack of “Bubba” or “Joe Six Pack” candidates - white men aged over 40, born in the South and without college degrees.

Mr Buskey tells The Independent the make-up of the jury is “tremendously concerning” and already raises concerns about the validity of the verdict.

“It is tremendously concerning and risks doing real harm by keeping the voice of Black people in the community out of it,” he says.

“Usually we see a Black defendant on trial in the South who is facing an all-White or nearly all-White jury.

“This case is flipped on its head where the defense has - by the judge’s own admission - engaged in selection that racially discriminates.”

He adds: “This raises serious doubts about getting justice and it’s a big risk and a shame as I’m sure the jurors selected will do their best but when you have a situation where Black people have been kept off the jury intentionally because of their race, then it undermines the verdict one way or another.”

Parallels with George Floyd

The jury is indeed drastically less diverse than the jury which convicted White police officer Derek Chauvin of the murder of Black man George Floyd in Minneapolis back in April.

In that case, the 12 jurors included one Black woman, two multiracial women and three Black men.

There’s no doubt that parallels will be drawn in other ways between that trial and this.

Like Mr Arbery, Mr Floyd’s killing on Memorial Day 2020 was captured on smartphone footage.

This footage went viral across the globe and sparked a movement calling for racial justice and an end to police brutality and systemic racism against Black people.

The footage was also key to the charging and conviction of Mr Floyd’s killer.

And while Mr Arbery’s death came three months before Mr Floyd’s, his case moved further into the spotlight as part of the Black Lives Matter protests which came out of Mr Floyd’s death.

According to Mr Buskey, there are a couple of other things that connect these cases on a broad level.

One, he says, is the “presumption of guilt that Black people in this country still have to face when they are doing things like jogging in the street” and the policing of Black people by White people.

“The first organized police force in this country was a slave patrol of White citizens, like the McMichaels, empowered to enforce the law to the Black population,” he says.

“The parallels to the McMichaels are hard to ignore. And then if we think about the development of policing in the George Floyd case, it’s the same.

“The police trying to control him and other black bodies by literally choking the life out of him.”

The second, he adds, is that whatever the outcome in the current trial, both cases show how the courts can bring “limited accountability” for the racism in today’s America.

“Even if the McMichaels are held accountable, this case speaks to a much broader issue of how race plays out in everyday life,” he says.

“The court can decide if an individual is guilty of an offense but it cannot put the issue of racism on trial.”

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments