'Prisoners are people first': America's inmates are ready for their #MeToo moment

At least 200,000 people are sexually abused in detention centres each year, yet their stories have been absent from mainstream movements

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Jan Lastocy was in a Michigan prison in 1998 when a new guard first began raping her. The months of assault began while she was at work in a warehouse that serviced a men’s prison; the guard also worked in the warehouse.

Ms Lastocy never told anyone what happened her while she was in prison – or for some time after she was released – but an investigation later revealed that she was one of several women the same guard had raped repeatedly.

Ms Lastocy and her fellow survivors eventually settled a $100m (£72m) class action lawsuit against the state of Michigan. She is now a vocal advocate against prison rape and understands that her experience is all too common.

“A lot of people think, ‘You’re a criminal, you deserve whatever happens to you,’” Ms Lastocy told The Independent. “I want people to know that we’re women first, prisoners second.”

In the current conversation about sexual harassment and assault, sparked by the #MeToo movement and advanced by campaigns like “Time’s Up,” stories like Ms Lastocy’s – stories about abuse of incarcerated women – have been largely invisible.

That is not because they’re uncommon. According to a 2012 report from the Department of Justice, at least 200,000 people are sexually abused in detention centres each year.

Approximately half of all reported instances of sexual abuse in prison are allegedly committed by prison guards.

Of course, those on the outside don’t need to study statistics to know prison sexual abuse is a major problem: Prison rape is often used as a punchline in movies and TV shows – the ubiquitous “don’t drop the soap” joke can be found everywhere from 2 Fast 2 Furious to Family Guy.

Given that incarcerated women are about 30 times more likely to experience sexual assault than women on the outside, prison rape seems a natural point of focus for anti-sexual abuse campaigns.

Yet incarcerated women have not been centred or even meaningfully included in the recent resurgence of Me Too, or by Time’s Up, an anti-workplace sexual abuse campaign launched by women in Hollywood.

When the founders of Time’s Up announced the campaign, which includes a legal defence fund for working-class women who experience sexual abuse at work, incarcerated women weren’t even mentioned.

Some may argue that the omission is based on Time’s Up’s mission of supporting working women, but incarcerated women are also workers. In fact, Ms Lastocy was raped on the job while she was behind bars.

Indeed, experts say prison sexual abuse shares many similarities with the workplace sexual harassment that has become the focus of the Me Too and Time’s Up movements – from the daily encounters with perpetrators to the skewed power structures at play.

Cindy Struckman-Johnson, a University of South Dakota psychologist and member of the National Prison Rape Elimination Commission, likened harassment by a boss to sexual abuse from a correctional officer. Harassment by coworkers, she said, is similar to harassment by a fellow inmate.

For incarcerated survivors, however, options for recourse are much fewer.

“There is essentially no escape,” Ms Struckman-Johnson said. “No report to [human resources], no relief at 5pm, no switching jobs. As a prisoner, you will remained confined and you will have to encounter your abusers every day and night.”

This power imbalance can be even worse at Immigrations and Customs Enforcement detention centres, where immigrants suspected of visa violations or illegal entry are held before their court appearances.

In many of these cases, immigrants come to the US fearing death or torture in their home countries. According to advocates, some of these women will do anything to decrease their chances of deportation – even if it means staying silent about sexual abuse in detention.

“Often the abuser will put it in terms of, ‘If you speak out about this, it’s going to be a negative mark on your record, and the judge is going see that. They’ll know that you’re a liar and they’re not going to let you stay in this country’,” explained Sofia Casini, the programmes coordinator at immigrants’ rights group Grassroots Leadership.

She added: “The women are unsure about what could or couldn’t happen, and will then keep silent because of it.”

Innumerable victims in prisons and detention centres are silenced each year by this kind of abuse of power. And even when victims do reports abuse, it is often ignored.

In the two years between May 2014 and July 2016, for example, the Department of Homeland Security inspector general investigated only 2.4 per cent of the complaints sent to his office, according to records obtained by the Community Initiatives for Visiting Immigrants in Confinement.

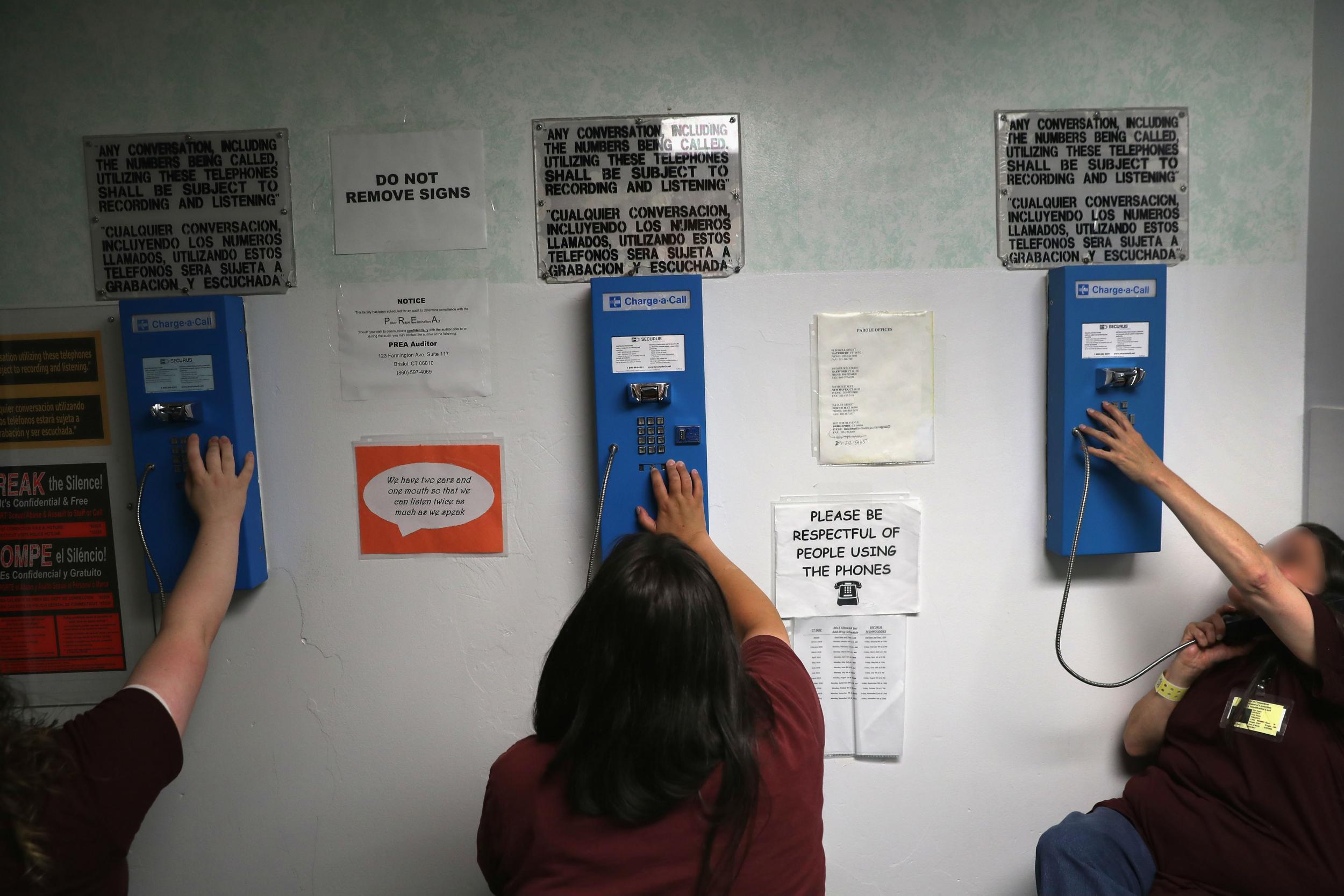

Adding to the problem is the fact that prisons and detention centres tend to be isolated, both geographically and technologically.

Jesse Lerner-Kinglake, communications director for Just Detention International, an organisation that works to end sexual abuse in all detention facilities, told The Independent that most prisons are “secretive and closed off,” and incarcerated people do not have access to the internet. Thus, participating in social media campaigns such as Me Too is not an option.

Just as importantly, people outside prison tend to hold very negative feelings towards incarcerated people. Mr Lerner-Kinglake said, that in, general, people on the outside “have very little empathy for someone who may have committed a crime”.

Ms Lerner-Kinglake also believes that many people probably feel prisoners deserve to be raped. “Some people feel [sexual abuse] is a deterrent, or a justified punishment,” he said.

A recent sentencing hearing for former Olympic team doctor Larry Nassar showed the popularity of this sentiment. After sentencing Mr Nassar, who plead guilty to sexually abusing multiple young gymnasts, Judge Rosemarie Aquilina said: “Our constitution does not allow for cruel and unusual punishment. If it did, I have to say, I might allow what he did to all of these beautiful souls – these young women in their childhood – I would allow someone or many people to do to him what he did to others.”

Ms Lastocy took serious issue with the judge’s statement. “Not even he deserves it,” she said.

There are signs, however, that the current movement is trickling down to affect those in prison. Just as jokes about the Hollywood “casting couch” have become taboo after sexual assault allegations were levelled against Harvey Weinstein, experts hope crude remarks about prison sexual abuse will fall by the wayside as well.

Deborah LaBelle, a Michigan-based attorney who regularly files lawsuits on behalf of incarcerated people, saw a sign of this change in a recent courtroom appearance. She had filed a suit on behalf of children who claimed they were being abused in prison, and was standing in front of the judge waiting for a verdict.

Instead of staying stoic and emotionless, Ms LaBelle said, the judge opened up to the courtroom about her own experience of being sexually harassed as a young lawyer.

“Usually judges are like,‘This has nothing to do with me’,” Ms LaBelle said. “But I think partly because of the Me Too movement, I think she saw past that ... I don’t think that would have ever happened [without this movement].”

But activists say that moving this kind of empathy from the fringes to the mainstream will require a profound cultural shift. Ms Casini said more oversight must be implemented in prisons and detention centres. Ms LaBelle said male guards should be removed from direct supervision roles in women’s prisons.

Mr Lerner-Kinglake suggested implementing safe reporting channels inside prisons, and providing medical and mental care after abuse. But most importantly, he said, everyday people must learn to change their mindsets.

“People need to start treating prisoners like ‘regular’ rape victims,” he said. “It’s important to remember that prisoners are still people first, and that’s never going to change.”

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments