New York is banning plastic bags – but will the rest of the US follow suit before it's too late?

Experts say such restrictions are a crucial tool to cut pollution and emissions – but they face tough obstacles

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

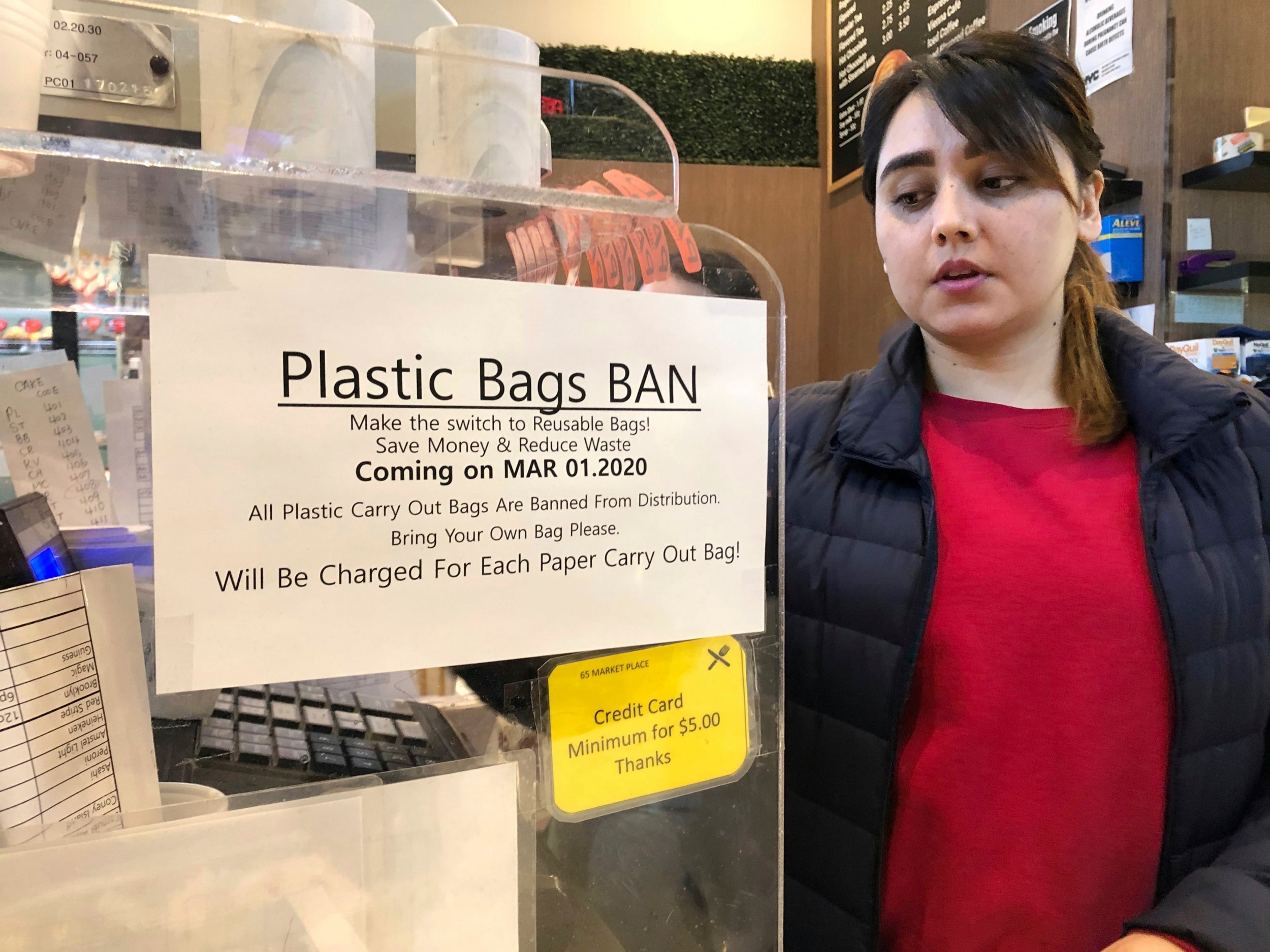

Your support makes all the difference.New York state has become the latest battleground in the plastic bag wars after banning them from stores.

A new law, that went into effect on Sunday morning, prohibits the distribution of single-use plastic bags.

The state, which uses an estimated 23 plastic billion bags a year, announced it will delay enforcing its 2019 plastic bag ban for a month after a lawsuit from bodega owners and a plastic-bag manufacturer, meaning stores will not be fined for disobeying the new rules until 1 April.

Earlier, two grocery chains took out a full-page ad in the New York Post blasting the ban as an "absurd law," warning that "billions of trees will die".

Conflicts like this have been simmering locally across the country for years, but in 2020, the action reached a new level. Six state bag bans passed in 2019, many of which will go into effect this year, and more are advancing in legislatures across the country in places like Colorado and Maryland, plus an unprecedented federal plastics bill proposed in Congress in February. China is outlawing all non-degradable bags by 2022. Experts say the bans are a crucial tool to cut pollution and emissions, but they face tough obstacles before they can make their full potential impact on the climate.

"Plastic bags are a first-class environmental nuisance," says Eric Goldstein, New York City environment director at the Natural Resources Defense Council (NRDC), noting that many end up as litter, clogging storm drains and polluting waterways.

In 2050, according to the World Economic Forum, there will be more plastic than fish in the ocean by weight. Even more crucially, Gonstein added, bag bans cut reliance on fossil fuels because plastic is made from oil and its byproducts.

"Single-use plastic bags are also an economic engine for the fossil fuel industry," he says. "If we want to take on the climate crisis, if we want to cut back on global warming, we've gotta find ways of reducing our reliance on single-use plastics."

All around the country, this strategy in tackling a global problem has risen from the local level, with city bans leading to state policies. In New York state, according to Elizabeth Moran, environmental policy director at New York Public Interest Research Group, there was a "perfect storm" of local changes that inspired change. In 2017, China decided to stop importing American plastic waste, causing a recycling crisis, and various municipalities around New York state began passing local bans, including New York City, though its ban was later overturned.

"There's a lot of ground level support for this," she says. "I think it's particularly notable with different environmental policies, particularly ones dealing with plastics, they started on the local level."

A similar local "domino effect" took place ahead of Maine's 2019 bag ban, according to Sarah Nichols, from the Natural Resources Council of Maine, which pushed for the bill. Starting with Portland in 2014, different cities and towns began passing differently worded bag bans until the retail industry threw up its hands.

"They were tired of fighting it," she says. "They knew at some point we probably could've passed a bill without them because there was so much momentum in the state. They recognised that and they wouldn't have gotten something they like."

Instead, environmentalists and retailers got together and worked out a policy that was stronger than the previous local ordinances, and included what policy experts say is a must to be effective: a fee on paper bags, too.

"If all that happens is a shift from plastic to paper, that's trading one set of environmental problems for another," says the NRDC's Goldstein. "They're not really the solution either."

Instead, what's needed is a total shift away from single-use plastics. Now that California, Hawaii, New York, Connecticut, Delaware, Maine, Oregon and Vermont have passed various types of bag bans in the last few years, eight total states are on their way to this goal. Meanwhile, thanks in part to the well-funded and effective plastics lobby, 15 states have so-called pre-emption laws, which prevent governments from regulating plastic and other types of containers.

While opposing sides duke it out at the state level, the plastic ban conversation has also reached new heights nationally. In early February, Senators Tom Udall and Jeff Merkley, as well as Representatives Alan Lowenthal and Katherine Clark, all Democrats, unveiled the Break Free From Plastic Pollution Act. The proposed law would require plastics producers to fund recycling programs, reduce or ban various non-recyclable, single-use plastics, and would freeze new plastics production facilities ahead of an expected doubling in production over the next 20 years.

Jennie Romer, from the Plastic Pollution Initiative at the Surfrider Foundation, helped craft the bill, and she says it's an unprecedented step at the national level to treat plastics as a consumption issue, not solely a recycling one.

"This is definitely the first attempt to really regulate it from really a source reduction angle, and in a comprehensive way," she says.

She's been waiting for this moment for years. As a law student, Romer interned on the Board of Supervisors as San Francisco became the first city in the country in 2007 to pass a bag ban.

"We wouldn't get to the point where we are now if we hadn't seen bag bans 10 years ago to get people to start thinking about it," she says.

But whether America gets any further on plastics at a national level depends on who sits in the White House, and who controls Congress.

"It seems like every day a new story breaks about the president's administration rolling back critical environmental protections," says NYPIRG's Moran. "The political environment on a national scale is really going to be tough to break through, so the state-level efforts are going to be very important, especially in building pressure so a national effort comes to be, because of course that is the ideal solution."

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments