A coroner raised the alarm over fentanyl for years – then it took her son

Alfarena McGinty signed countless death certificates with the powerful synthetic opioid, before receiving a call no parent should have to answer. She tells Richard Hall her story

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

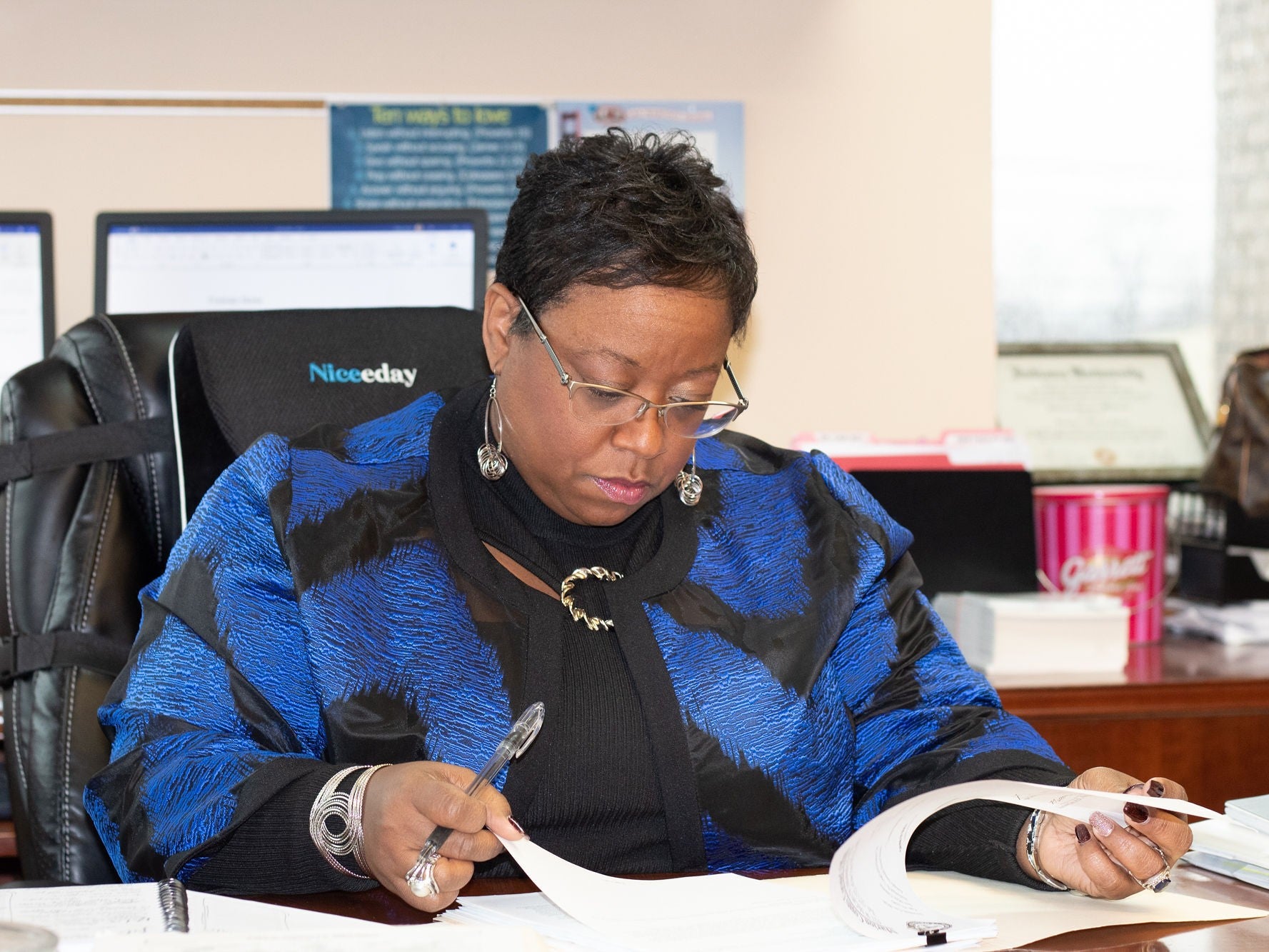

Your support makes all the difference.In every death there is a story, and it is Alfarena McGinty’s job to tell it. For more than two decades she has worked in the Marion County coroner’s office in Indianapolis, a job that requires her to carefully investigate and document the final moments of the city’s dead. There is not much she hasn’t seen.

But about six years ago she started to notice something strange. The opioid crisis was already raging across the country and fatal overdoses were common, and yet she saw a shift taking place. At more and more death scenes she discovered the presence of fentanyl — a powerful synthetic opioid that is 50 times more potent than morphine.

“I started trying to figure it out,” she said. “I sent alerts to the health department, to the police department, to mental health and public health agencies to let them know that we’re seeing this increase in fentanyl deaths.”

She went even further, starting an agency taskforce to look at the phenomenon and implementing investigative practices to discover why it was causing so many deaths.

Things continued to get worse. Fatal overdoses rose dramatically in the subsequent years and fentanyl became the primary killer. The number of deaths was “simply ridiculous”, she says.

McGinty signed countless death certificates of other people’s sons and daughters with fentanyl as the cause as it spread across the city of Indianapolis like a virus. Then one day she received a call from one of her own employees.

“She asked me if I knew someone named James Williams,” she says. “Immediately I asked how old he was. She said he was 27. I said, ‘Yes, that's my son.’

“I asked her, ‘Is he dead?’”

‘He just lost track of everything’

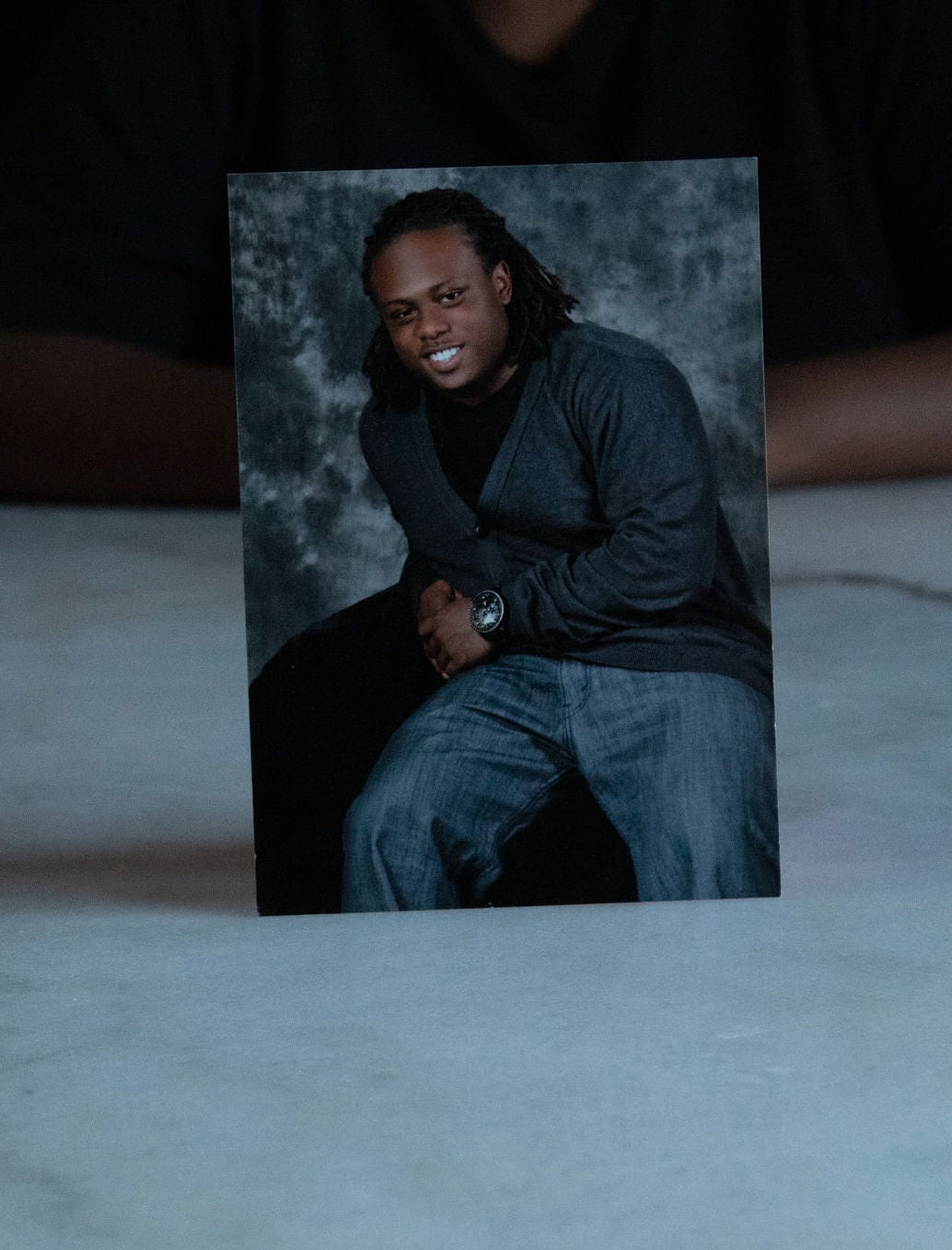

James Williams, known to his friends and family as Jimmy, died from fentanyl poisoning on 24 July last year, becoming a victim of an spiralling epidemic that has grown more deadly during the coronavirus pandemic.

More than 100,000 Americans lost their lives from overdoses in the 12 months ending in April 2021, the highest annual number ever recorded and an increase of nearly 30 per cent on the same period in the previous year.

America’s opioid crisis began more than two decades ago when pharmaceutical companies created powerful painkilling drugs they falsely claimed were not addictive. That transformed into a deadly heroin addiction crisis. Today, fentanyl is taking over. Last year it was responsible for two-thirds of overdose deaths. Williams was one of them.

Our Supporter Programme funds special reports on the issues that matter. Click here to help fund more of our public-interest journalism

When her son died, Alfarena McGinty set out to find answers about his death in much the same way she had done with thousands of strangers before him in her professional life. Who was he with? What did he take? What did he think he was taking? What drugs were found at the scene?

As a coroner, there was an immediate and reflexive need for her to know the answers to these questions — to tell the story of his death. But as a mother, that story would be much harder to tell, and harder still to deal with.

Jimmy was her firstborn son. It was clear early on that he was bright; he started talking before most other children and at three years old he went to a private school where he learned Spanish. By the time he was in elementary school, Jimmy was bilingual.

In those early years, Jimmy’s father — McGinty’s first husband — became addicted to drugs. They were living in Indianapolis in a difficult neighbourhood. She says it was “not where I wanted to raise my boys”, so when Jimmy was nine, McGinty took him and his brother to the suburbs and away from the trouble.

“After I saw his father and what he went through, I wanted them out of that whole neighbourhood. I wanted them out of that environment,” she says.

Their household grew. McGinty’s second husband had three girls and they all moved in together. Jimmy thrived out there, watched closely by his mother and stepfather, who was a deputy sheriff.

“I was very strict. Like, you couldn't hang out, you had to be in before dark. I was just a strict mother because I was raised by my strict dad. There were no issues. He didn't smoke weed in high school. He wasn't trying to do all the gang-banging stuff,” she says.

He played every sport he could until he eventually settled on American football, which he excelled at. He was short, but extremely quick on his feet, so he became a running back. As he entered his senior year of high school, Jimmy had options. He was great at football and his grades were excellent. College scholarship offers came flooding in. After a summer spent carefully reviewing offers in 2011, he settled on Wittenberg University in Springfield, Ohio.

“He loved it. He loved the school. He loved the football programme — he was on a championship team. He was just in awe of the place. He was just the kind of kid that loved learning,” she says.

But Jimmy was also a young man living away from home for the first time. Like many college students, he took advantage of those new freedoms.

“He told me that he was so used to having that structure and routine at home, and when he went to school, he lost that. He didn’t know what to do with himself. That's in part how he ended up starting to smoke weed and starting to use drugs and going to parties, because he didn’t have to face me every day,” she says.

“He just lost track of everything.”

I took him to the morgue and I said ‘Look, this is where you’re gonna be if you don’t stop this.’

It is not always easy to pinpoint the exact moment people set out on a path to addiction. There is not always an obvious fork in the road. But looking back now, it’s clear to McGinty that what came next was the start of something. In 2015, Jimmy was kicked out of college for marijuana possession.

“That broke his heart. It killed him. He felt like a failure because he didn’t finish school and that haunted him for years,” she says. “You know how people have this dark thing that they keep falling back to when they start using? His was not finishing college.”

“I even told him, ‘I'm not disappointed. I mean, you didn't finish school. Okay. You have an opportunity to go back. I'm not mad at you. It took me nine years to finish my undergrad, so if it takes you that amount of time, all you have to do is do it.’”

He enrolled in another college close to home, but it didn’t work out. He tried another, and left that one too. By this time he was using Xanax regularly, a habit he had picked up at college. He had dabbled in cocaine there, too. Social drug-taking is not unusual at college, and many young adults see it as a rite of passage. But once he was removed from that environment, Jimmy struggled to stay on track.

When he got back to Indianapolis, Jimmy began hanging around with a new set of friends. In 2016, he was shot. McGinty says he “was in the wrong place at the wrong time.” Ironically, the drug that tipped Jimmy into a severe addiction came from a doctor who prescribed pain medication after the shooting.

“At that point he really kind of realised he was in bad shape. He acknowledged that he had an addiction,” says McGinty.

‘I’ve seen this crisis sort of explode’

At the same time McGinty was watching her son falling deeper into addiction at home, she saw the devastating results of drug use at work.

Across the country, overdose deaths from opioids more than doubled from 21,088 in 2010 to 47,600 in 2017. It was McGinty’s job to make sense of this. Coroners are often the first to notice patterns in the causes of death, long before they are interpreted and studied at the official level.

McGinty was born nosy — something she says has helped her do her job well. When investigating causes of death she often goes beyond the call of duty. She goes out on the street and speaks to people. There is a certain amount of detective work involved.

“I ask questions and people talk to me for whatever reason,” she says. “I remember back during the cocaine and crack epidemic, I was talking to prostitutes who were selling sex for drugs and money, and they told me what was going on in their world.”

When overdose deaths began to rise sharply in 2015, naturally, she wanted to know why.

“I've seen this crisis sort of explode over the last six years. I was always interested in data and statistics, so we started kind of really counting these numbers. Every year they were going up and up.”

Initially it was heroin that was causing most of the deaths, but fentanyl was increasingly being found on the scene. Her office partnered with the local university to track overdoses and the drugs that caused them. She also pushed for changes in how they reported deaths. For more than 20 years, death certificates noted the cause only as an overdose, without specifying which drug.

“We weren't capturing what was actually happening with the drugs that were being found in the systems of many of the deceased. That's a whole missing piece of the puzzle,” she explains. “We needed to actually document the drugs that were found in the system, because that is critical to identifying what's happening in the community.

“When we started doing that, we really started to see these crazy numbers of fentanyl. It was an explosion of multiple deaths a day, multiple deaths a week.”

What McGinty was seeing in Indianapolis was happening across the country. Fentanyl is a powerful synthetic opioid that is similar to morphine but is 50 to 100 times more potent. It acts faster on the body and lasts longer than other opioids, and since its emergence in the US in 2014 it has slowly encroached on heroin’s place in the drug market. Most of it comes to the US from Mexico or China, but it can be made by any competent chemist in a lab.

In 2010, just 14.3 per cent of opioid-related deaths involved fentanyl. By 2017 it was at 59 per cent, and in the 12 months leading up to April 2021, 64 per cent of opioid deaths were related to synthetic opioids, mostly fentanyl, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Because of its availability, dealers mix fentanyl with other drugs such as heroin, cocaine, methamphetamine and MDMA to increase potency. It has also found its way into counterfeit prescription pills like oxycodone (Oxycontin, Percocet), hydrocodone (Vicodin), and alprazolam (Xanax); or stimulants like amphetamines (Adderall). Often, the people taking those pills do not know they contain fentanyl.

In September last year, the DEA said law enforcement was seizing deadly fake pills at record rates. More than 9.5m counterfeit pills were seized between January and September 2021, and two out of every five pills with fentanyl contained a potentially lethal dose.

McGinty was already in deep with her investigation. Her office started collecting all the drugs that were at the scene of a death, not just what was found in the system. They were looking for more than the actual drug that caused the death, but also why it killed them.

“I'm all about asking questions. I'll talk to a drug dealer in a minute,” she says. “I’ll call around and talk to families that have been impacted and ask what was their loved one’s drug of choice. If their drug of choice was cocaine, but they had no cocaine in their system, and they tested positive for fentanyl, then I go back to see what was on the scene. Was it a white powder? Was it a pill? Was it a blue pill? Was a baggie found?”

She was trying to tell the story of these deaths. Every time they took a pill or shot up heroin — drugs they had done hundreds of times — they were at risk of a fatal dose of fentanyl without even knowing they were taking the synthetic drug.

“They never knew what they were getting,” she says.

‘I’m different because as an investigator, I wanna know’

McGinty used to take her son to the morgue. She made him go. She wanted Jimmy to see the cost of his addiction; to see how many people were dying while taking the same drugs he was taking.

“We were so open with each other. I took him to the morgue and I said, ‘Look, this is where you're gonna be if you don't stop this.’ I would bring him case after case after case and tell him, ‘They took these pills. They took Xanax or whatever, and they're dead.’”

By 2017, Jimmy had already been in rehab once, and because of an arrest for possession of pills he was in a drug court programme that required him to go to treatment and test every couple of days. The programme was supposed to act as a deterrent, but he couldn’t break out of the cycle.

“He would have these periods of time, maybe two or three months, where he would be sober, but then he would relapse,” McGinty says. “When he relapsed and he had a positive drug screen, he would have to go into jail for like three to five days. And he couldn’t go to jail sober. So he would use and go through the whole cycle again.”

Jimmy always managed to have a job, though. He was bright and affable, which helped. He worked server jobs mostly, and kept them for a while until he relapsed again. When he was clean again he could easily find another.

The next year, in 2018, Jimmy began using heroin. McGinty says he was hanging around the same friends who he took drugs with, and he was acting as a middle man between people he knew and drug dealers. No matter how many times he got clean, drugs were always around.

Throughout it all, McGinty had completely open and honest conversations with her son about his addiction. Beside the trips to the morgue, she always knew where he was and most of the time he was honest about what he was using. She wanted to know everything, and she wanted to give him all the help and support he needed to get clean. She even asked him to give her one of the pills he took so she could test for fentanyl.

“There are a lot of black parents and families that are in denial or they either wash their hands of it. If they know you're using, they don't wanna talk about it,” she says. “I wanted to talk about it. Like what is driving you to use? What are you feeling that is making you want to use? Those were our conversations. I'm different because as an investigator, I wanna know.”

That same year Jimmy began using crack cocaine. He told his mother it was because everyone around him was using it. He thought he could use it just once, but he quickly became addicted.

“He said when he started smoking crack cocaine, that was the beast that he could not get past. He just absolutely couldn't make decisions. So then he would use whatever was available,” she says.

“He would smoke crack for a couple days. And then in order to come down he would take the Xanax. And obviously the Xanax are from the street, so of course they were laced with fentanyl.”

In 2020, Jimmy overdosed on heroin. He told his mother the whole story. He used it intravenously and had asked someone else to inject him because he didn’t like needles. “When he overdosed, they put him outside the house and someone from the neighbourhood called an ambulance. This was the same neighbourhood, I removed him and his brother from when I moved to the suburbs. Somehow, he was drawn back to that place.”

‘His siblings and I knew this was the end result’

The start of 2020 brought with it the arrival of the coronavirus pandemic, which put McGinty’s place of work on the frontline of another nationwide crisis. By February, the morgue where she worked had run out of space and they did not have enough forensic pathologists to handle the case load.

At the same time, the pandemic created a deadly combination of circumstances that sent the opioid crisis into overdrive. The forced isolation caused by lockdown measures kept people away from their treatment. Stimulus cheques, which were a lifeline to millions across the country struggling financially, caused a spike of overdoses among drug users who went out to buy drugs. Nationwide, more than 90,000 people are thought to have died from overdoses in 2020, up about 30 per cent on the year before.

Something else was happening, too. The overdose death rate was increasing faster among Black men than any other group. According to the CDC, there were 54.1 fatal drug overdoses for every 100,000 Black men in the United States in 2020 — an increase of 21 per cent since 2015. That was similar to the rate among American Indian or Alaska Native men, who saw 52.1 deaths per 100,000 people, and well above the rates among white men (44.2 per 100,000) and Hispanic men (27.3 per 100,000). This marked a departure from previous years when Black men were considered less likely to die from an overdose.

Jimmy moved back in with his mother in the early months of Covid and lockdown. He had just got out of treatment and had nowhere to go. He tried to do the online meetings but he hated it.

“It took some convincing to allow him to come back to my house. But we became very close, just in our conversations and communication, about what his history had been, because I needed to understand that,” McGinty says.

He would come and sit in her home office and talk about his use and his battle for sobriety. She would learn things about her son’s addiction that she would take to work with her. It was almost impossible to separate the two. Her son told her one day that the isolation of lockdowns was making it difficult for him to stay clean.

“People were relapsing left and right because they were stuck and they had nowhere to go. My son told me: ‘The mind is the devil's playground.’ So they were bored. They didn't have support.”

“Based on what my son was telling me, I wanted to dive deeper into our drug overdose deaths and what our investigators were gathering from death scene investigations, and talking to the families as well. It kind of changed the way that I operated at the office with regard to these drug overdose deaths.”

In the months before his death, McGinty knew her son’s situation was serious. They talked openly as a family about the dangers of his addiction.

“We talked together with his siblings at our kitchen table about planning his funeral. We talked to him about what he wanted his funeral to look like. Or did he want a funeral? Did he wanna be cremated? Did he wanna be buried? We had that conversation probably eight months prior because we knew he was using, and his siblings and I knew this was the end result,” she says.

It was to no avail. McGinty remembers the last few days of Jimmy’s life in minute detail.

When he left rehab in early July of 2021, he came back to his mother’s house again. He told her he needed to disconnect from all his friends to stay clean. But it wasn’t long before he was heading out again.

Jimmy found himself in trouble with the police in several different counties. They were relatively minor infractions like driving with a suspended licence and possession of Xanax, but they required that he surrender himself to more than one police force. He was using again, so he checked himself into a rehab. While he was in treatment for his addiction he missed some court dates, which meant that he would again have to spend time in jail.

“He literally cried when he saw the paperwork that he missed the court date,” McGinty says. “He said ‘I can't deal with this. This is too much to deal with.’”

In a text message, a week before he died, he wrote to his mother: “I can’t deal with this jail shit-its heavy. Its no excuse when you are faced with grown man consequences, its easy to say—yea I’m gonna face it, then it gets here and I don’t know how to cope.”

Read more special reports from our Supporter Programme

Jimmy left the house on a Monday and was supposed to turn himself into the police a couple of days later. McGinty spoke to him a few times over the coming days, and again on Thursday. She knew he was using again because she knew his routine. And he told her as much. In their last phone call, he told her he was going to stay with a friend on the southside of the city.

“On Friday, I didn't hear from him. I knew something was wrong because he usually would call or text me and tell me where he was.”

‘I see these deaths every single day’

It was a Saturday afternoon around midday when an investigator at McGinty’s office called her phone. She was used to them calling to discuss cases or investigations they were working on.

“She asked me if I knew someone named James Williams,” says McGinty. She knew three: Jimmy, his father, and his grandfather, and all of them suffered from addiction. She knew what was coming. She asked how old he was. When her colleague answered 27, she replied: “Yes, that's my son.”

“I screamed. To be exact I screamed ‘I told you to f***king stop using. I told you to stop using. That’s all I could scream. I cuss a lot.”

McGinty was both a coroner and a mother at that moment. Her investigation into her own son’s death began immediately.

“So I went to asking the questions,” she says.

McGinty’s colleague at the coroner’s office conducted the initial investigation. Jimmy had been with a friend in Greenwood, a suburb of Indianapolis. They had been using cocaine, heroin and Xanax together until about 4am. The friend had helped Jimmy to the couch because he was staggering. The next morning, the friend’s girlfriend found them both unresponsive. They had both overdosed. She called 911 and they were taken to the hospital. Jimmy died, his friend survived.

Fentanyl killed him. One of the drugs he took was laced with it, the investigation later found. McGinty never got to find out which of the drugs it was because hospital security threw away the bag they came in.

The examination of Jimmy’s body took place in McGinty’s office by a forensic pathologist who works for her. She watched them perform the exam.

“I absolutely could not believe that I was standing in that place watching that happen,” she says. “It was heartbreaking.”

“It was also something that I had tried to prepare myself for. I see these deaths every single day. I talk to parents and mothers and siblings and spouses every single day about these deaths. I know that you do not survive in this world continuously using drugs when there's fentanyl in everything,” she says.

“The only thing that brings me any kind of peace is to know that he did not suffer,” she adds. “I was very grateful that I know how fentanyl works in the system, it's like you just go to sleep.”

‘I don’t even know why I’m doing this’

It has only been a few months since she lost her son to fentanyl. After years of studying, investigating and seeing the fatal results of the drug every day in her job, and having her own family torn apart by its effects, she says there are still no easy answers to the problem.

“I don't even know what to say. I don't have an answer. I don't know. I've talked to police, I've talked to detectives, I've talked to the DEA and we're all at a loss. It’s just so different. But I'm trying to figure it out,” she says.

Dealing with the death of her son is an even more insurmountable problem. Even with the support of his family, the knowledge and warnings of his mother, and every opportunity to heal himself, his addiction was too powerful.

“He always said to me: ‘You raised a really good kid. I just have an addicted brain,” she says.

“He’d tell me about those people in treatment programs and say ‘they've had some hard lives. They don’t even have family to turn to, but I know you love me and took the best care of me. I don't even know why I'm doing this.’”

McGinty says she wants to help other families suffering the same pain as her — particularly African American families who may be suffering alone — by starting her own grief support group.

“I go to a support group and I’m the only African American there. There’s only about ten of us. I’m wondering if people don’t know or if people don’t want to share, I’m trying to get to the bottom of it.”

What is important to her now is telling her son’s story. She has reached out to the friend he was with when he died in the hope that he can shed some light on what happened. But she doesn’t just want to tell the story of his death, as a coroner does, but of his life.

“We spoke about me sharing his story,” she says. “I said I need to be able to share your successes and your failures. Because it's not just you going through this. If it helps someone else, then you know, that's what I wanna do.”