Man wins 37 year battle to overturn New York nunchuck ban using Second Amendment

Judge strikes down decades-old law as unconstitutional and lifts ban on manufacturing weapon

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

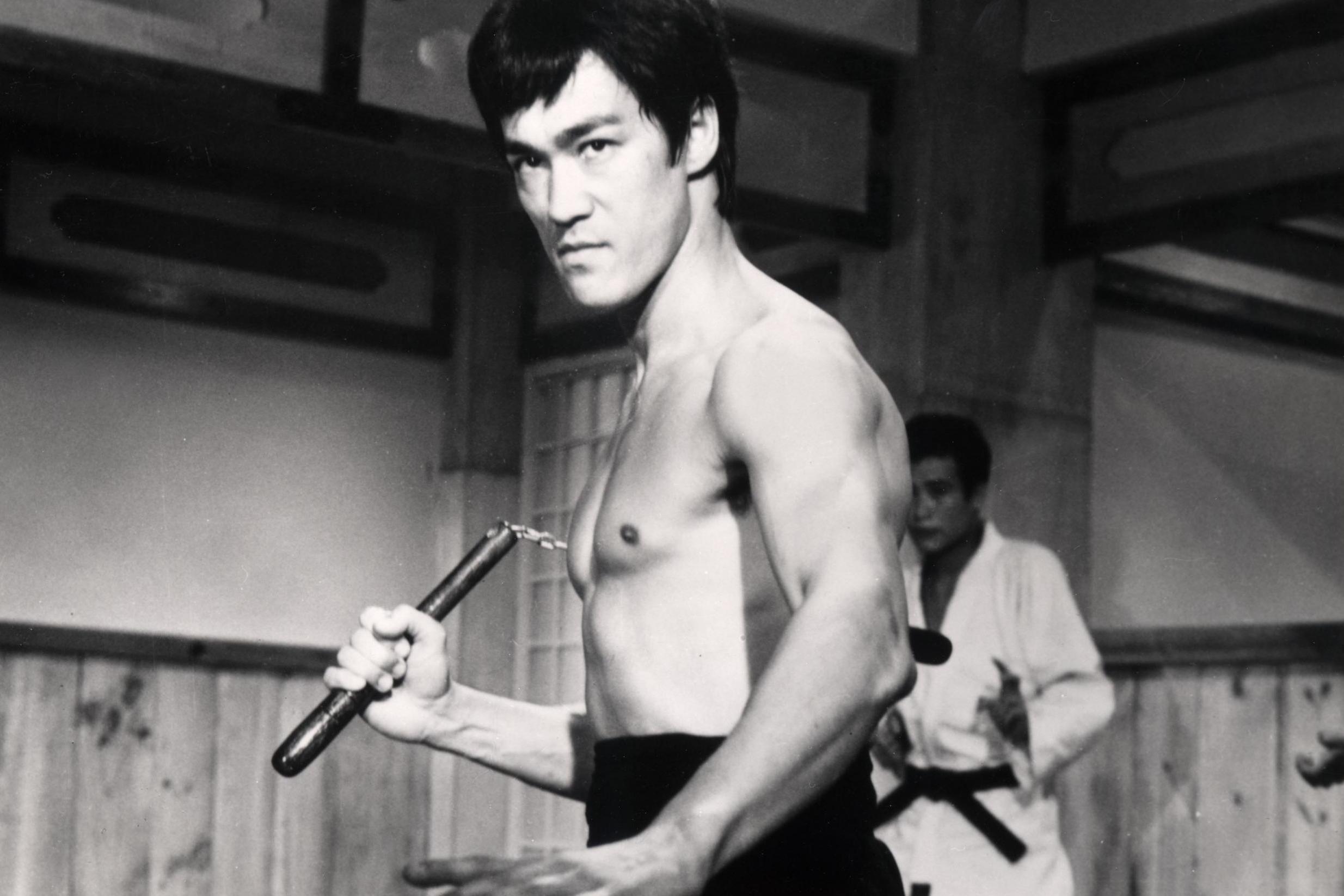

Your support makes all the difference.In the 1970s, the United States was in the middle of kung fu fever. A wave of martial arts movies washed onto American shores, making Bruce Lee an international superstar and “nunchucks” a household word.

Worried that young people inspired by the craze might use nunchucks to cause havoc, New York state politicians criminalised the weapon in 1974.

Shortly afterwards, a young man in suburban New Jersey began studying nunchucks, eventually developing a passion for them.

Four decades later, that formerly young man, James M Maloney, now 60, was in court battling New York’s ban on the weapon — and winning.

A federal judge struck the prohibition down, calling it unconstitutional. In her ruling, Judge Pamela K Chen, of US District Court for the Eastern District of New York, said nunchucks were protected under the Second Amendment, which guarantees the right to keep and bear arms.

It was a long-sought victory for Mr Maloney. “I’m still digesting it, honestly,” he said after the verdict.

“It is an instrument or weapon that is a lot more humane than penetrating weapons,” he said. “The swords, the guns, the knife — they all do their damage by putting a hole in somebody,” he said. Nunchucks do not.

The legal sparring over nunchucks — two rods connected by a chain or rope that were called by their Japanese name, “nunchaku,” in Ms Chen’s decision and “chuka sticks” in state law — began in 2000, when Mr Maloney was charged with possessing them in his home.

But Mr Maloney, a lawyer who teaches at the State University of New York’s Maritime College, said the origins of the case traced back to 1981, when he was arrested in New York City after doing a public demonstration with nunchucks.

That was the first time Mr Maloney, who had trained himself to use nunchucks after years spent studying martial arts, learned about the ban. The charge, which was easily resolved, planted the seeds for the legal case to come.

By the time he graduated from law school in 1995, Mr Maloney had already formulated the basic outline of a challenge to the nunchucks ban.

His reasons for first learning to use nunchucks went back to his childhood, he said. When Mr Maloney was six, he said, his father was fatally stabbed, so Mr Maloney was well aware of the danger that edged weapons like knives could cause.

Because nunchucks allowed their wielder to maintain distance from his or her attacker, Mr Maloney thought they would make an exceptional tool for self-defence.

In the ‘70s, martial arts movies were a huge cultural phenomenon that brought centuries-old nunchucks closer to the centre of modern popular culture. Impressed and inspired, droves of young people were twirling the weapons in their backyards and trying to avoid whacking themselves in the face.

But New York lawmakers worried some young people might be using the device nefariously. Officials were especially worried about “muggers and street gangs” who might use nunchucks to cause serious harm, according to Ms Chen’s decision. Out of concern for public safety, they passed a law to keep nunchucks off the streets.

All the while, public enthusiasm for nunchucks never diminished. They showed up in video games such as Mortal Kombat, comics such as Daredevil and cartoons such as Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles, in which an anthropomorphic adolescent reptile named Michelangelo wielded a set of nunchucks in each hand.

Mr Maloney’s affection for the weapon did not wane either. He developed his own martial arts technique. Nunchucks, he said, were an integral part of that style, which he called “Shafan Ha Lavan” — the Hebrew translation of “white rabbit.”

When he filed his complaint in 2003, Mr Maloney, who represented himself in the case, argued he had a constitutional right “to possess nunchaku in my own home,” he said.

The case then made its way through the court system, finally coming before Ms Chen. The Nassau County district attorney’s office tried to argue “the dangerous potential of nunchucks is almost universally recognised” and thus not protected by the Second Amendment.

But the judge said she did not see any evidence of that, noting the weapons were used most often in self-defence.

“The centuries-old history of nunchaku being used as defensive weapons strongly suggests their possession, like the possession of firearms, is at the core of the Second Amendment,” Ms Chen wrote.

In her ruling, Ms Chen went further than Mr Maloney had sought, striking down the entire ban on the weapon, as well as a related law preventing nunchucks from being manufactured or transported in New York.

The New York Times

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments