Nova Scotia health workers warned of nursing shortage years before death of young mother: ‘It’s definitely getting scarier’

Across industrialised world health care workers are warning of insufficient staff – and deadly consequences, writes Andrew Buncombe

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Health workers in Nova Scotia – where a young mother died after waiting six hours in an emergency room – say they have been warning for years of a critical shortage of nursing staff and how the system is “bursting at the seams”.

On 31 December, 37-year-old Allison Holthoff died after her husband took her to hospital after experiencing what she said was terrible pain in her stomach.

She died after waiting more than six hours to see a doctor at Cumberland Regional Health Care Centre, 120 miles north of the provincial capital, Halifax.

“We need change, the system is obviously broken. Or if it's not broken yet, it's not too far off,” her husband, Gunter Holthoff, said at a press conference. “Something needs to improve. I don't want anybody else to go through this.”

Yet The Independent has been told that for years medical unions and community health groups have been warning of a critical lack of staff, the result of gruelling working conditions, rising patient-nurse ratios, and people leaving for the private sector.

Currently, there are 1,500 nursing vacancies in the province, as officials struggle to recruit and retain staff, a crisis made worse by the Covid pandemic and, more recently, by the winter flu season.

The crisis in Canada is far from unique. While up to 40,000 people may die annually after experiencing what are called a serious adverse events (SAE) in Canada, those figures are proportionally lower than in the United Kingdom, with its National Health Service, and similar to the United States, where the health care system is overwhelmingly private.

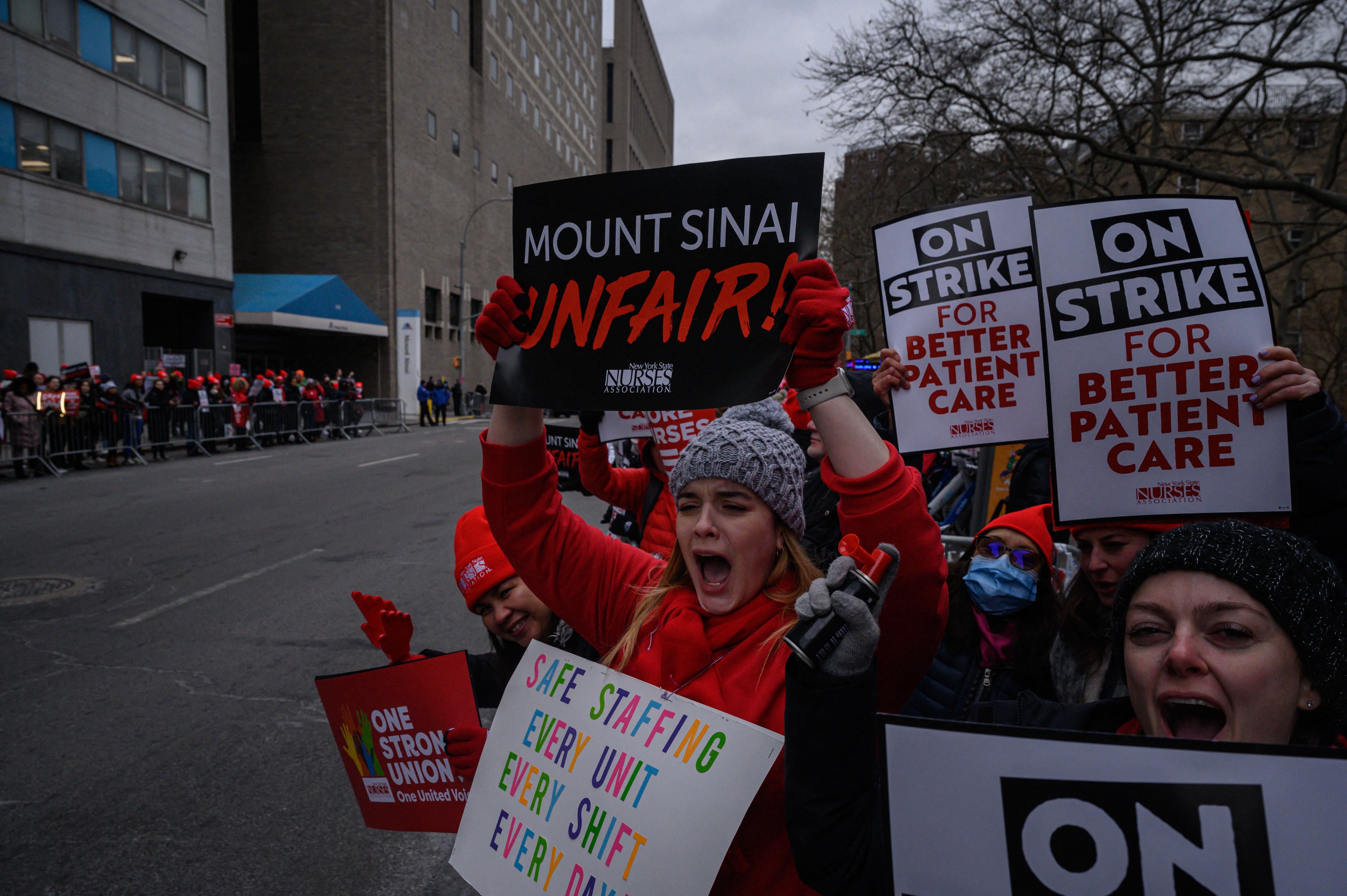

Indeed, the tragic circumstances that befell Holthoff are repeated across the healthcare systems of the developed world. Nurses from New York City to London are taking strike action to try and draw attention to what they say is a system past breaking point.

“People are admitting we have a problem in Canada, the US, UK, all the industrialised countries, but they're not in admitting the kind of issue that actually is behind that problem,” said Dr Robert Robson, a veteran physician and patient safety consultant from Dundas, Ontario.

“Namely, we've created a complex, adaptive system, and we don't know what to do about it. And there’s not a simple solution to that.”

Mr Robson said data showsaround 7.5 per cent of people who enter a Canadian hospital will suffer an SAE and that of those, 1 in 100 will die as a result. In Britain, the figure is more than 10 per cent, while in the US it is somewhere been the two.

He says as healthcare has become more specialised, officials have failed to put patient safety first and there has been a breakdown in the way care is provided.

To change that, and to reduce the number of incidents such as what happened in Cumberland, Nova Scotia, requires involving patients in developing improvements. One key area that has received much attention has been the shortage of nursing staff.

Hugh Gillis, vice-president of the Nova Scotia Government and General Employees Union, said last year he learned of an email sent to staff by managers at the Dartmouth General Hospital who said people were “dying” as a result of long periods waiting in hospital emergency rooms, even if their deaths were not actually happening in the ER.

“Nova Scotia emergency departments are just bursting at the seams, and they have been for years.” he said, speaking from Halifax. “It’s clear that the seams have finally let go and we need to take action to improve the system, that functions not only for workers but for patients.”

Mr Gillis, whose union represents health care workers and nurses at the Halifax Infirmary Emergency Department, said they had been raising the issue for a number of years, but with little response.

He said many nurses had left the public sector to work in the private sphere, which makes up part of Canada’s overall system. As so-called “traveling nurses”, they can earn two or three times what those in the public sector get paid.

“If you have 1,500 nurse vacancies, we need nurses in those facilities, and we it's not only recruitment, but it's also retention,” he said. “This is especially the case in especially in the emergency rooms.”

He said 10 years ago, nurses went on strike to draw attention to the crisis but we ordered back to work by the regional board, a quasi-judicial tribunal.

In the aftermath of Holthoff’s death, the regional authorities launched an investigation to try and discover what had gone wrong.

“I want to assure all Nova Scotians we remain committed to and focused on fixing our healthcare system,” said Health and Wellness Minister Michelle Thompson, a member of the Progressive Conservative Party of Nova Scotia, which won power in the regional assembly in 2021 elections.”

“We will act on what we learn from this investigation, and we will continue to act on what we’re hearing from healthcare workers, communities and Nova Scotians.”

Medical staff at the facility where Ms Holthoff died are represented by another union, Nova Scotia Nurses' Union.

Its president, Janet Hazelton, has also previously pointed to a lack of resources, but the union said it would make no comments until the investigation had been completed.

Health Canada, the federal department, did not respond to inquiries.

Alexandra Rose, provincial co-ordinator for the Nova Scotia Health Coalition, a non-profit made up of community members, as well as patient and healthcare advocates, said the situation at the moment was very concerning.

“It is definitely a very scary time. The staffing issues, struggling with backlogs from the start of Covid, the flu season, and all of these things. It's definitely getting scarier.”

She added: “I think everybody knows that. Change is happening, and we're just hoping it happens pretty fast.”

In an interview with the Canadian Broadcasting Corporation, Mr Holthoff said his wife’s death had left their three school-aged children with their mother.

“She was the most amazing person I've ever known,” he said. “She was great and everybody could get a helping hand out of her. If they needed help with anything, she was there for you.”

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments