Secrets of centuries-old inscription inside cave uncovered by Native American scholars

Writings are rare documentation of history as seen through eyes of Cherokees themselves

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

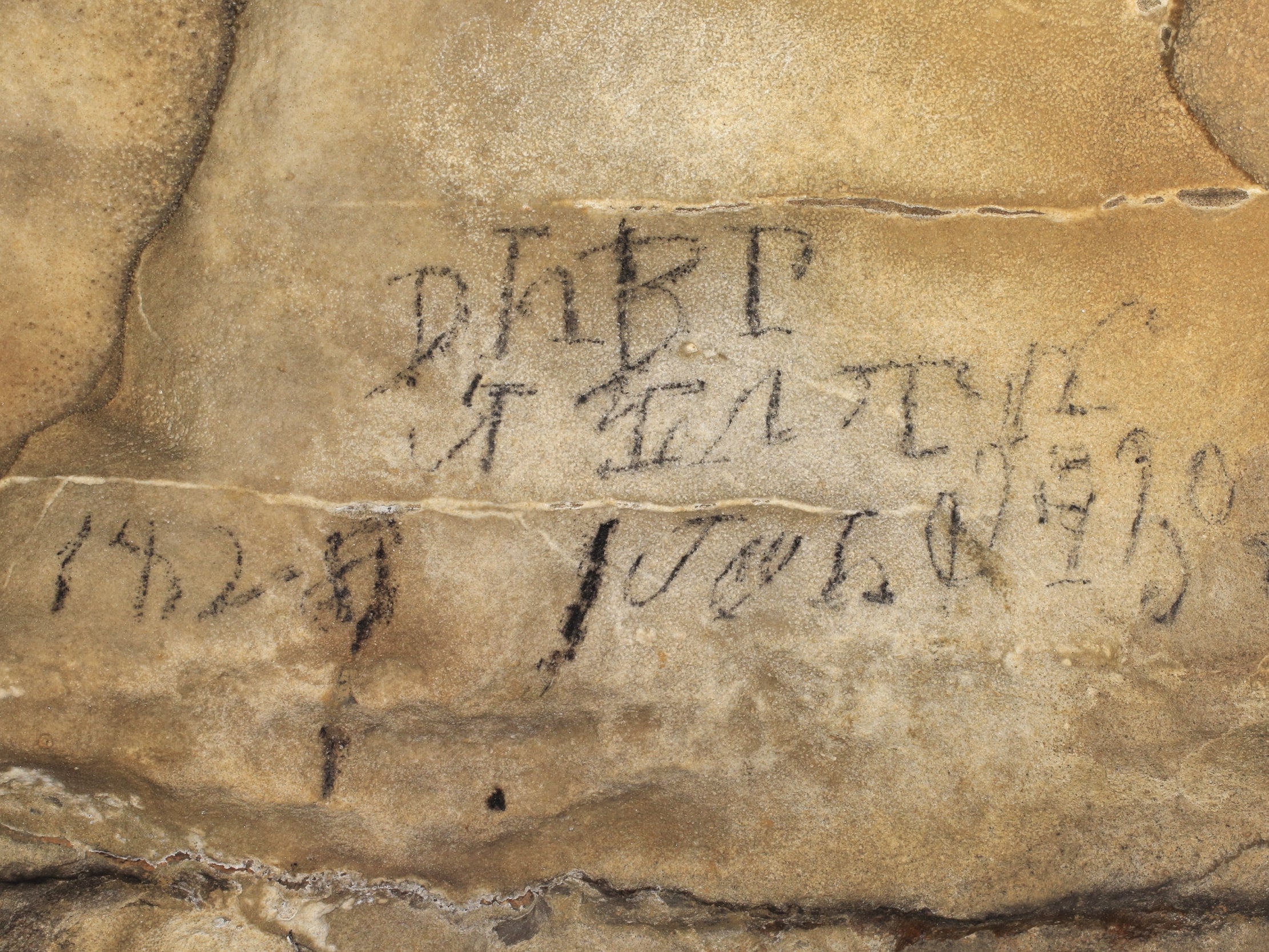

Your support makes all the difference.At first glance, it looked like a set of black numbers and letters written in English, perhaps with some symbols included.

It had gone unnoticed for nearly 200 years in a cave nestled in a wooded hillside overlooking Fort Payne, Alabama - population 14,000, about 60 miles southwest of Chattanooga, Tennessee - and was partially covered by graffiti.

But when cave explorers found the inscriptions, they realized the significance. After years of research and analysis, a team of Native American scholars and anthropologists determined the inscriptions are the first evidence of the Cherokee syllabary - the tribe's written system that uses symbols to create words - ever found in a cave. It details the "secluded, ceremonial" activities of the tribe that once occupied the area.

"People had probably been looking at and passing by this for years, but they just didn't know what they were looking at," said Beau Duke Carroll, a Cherokee who co-authored a story in the anthropology magazine Antiquity on the inscriptions.

The inscriptions inside Manitou Cave of Alabama are in the Cherokee syllabary developed by Cherokee scholar Sequoyah. He had enlisted in the US Army under Andrew Jackson to fight rebelling Creek Indians and had become interested in how whites used the alphabet to communicate.

Sequoyah eventually developed a written system from the Cherokee language, which became the tribe's official written language. The syllabary came to look similar to English letters so it would work on a printing press. Cherokees later published their own newspaper, the Cherokee Phoenix.

It was one of the earliest written systems for tribes and was invented from other alphabets, experts said. By the 1820s, scholars said, more than half of Cherokees could use the syllabary - a far higher literacy rate than most tribes had with their written languages. Using the syllabary was also helpful in allowing Cherokees to send messages as they contended with invading whites.

In the 1780s, Fort Payne, then known as Willstown, became much like a refugee camp of Native Americans who had sided with the British in the American Revolution and were being forced from their ancestral homelands as part of the government's relocation program, known as the Trail of Tears. It involved more than 100,000 Native Americans being forced to move to areas west of the Mississippi River.

Willstown was called the most important town in the Cherokee nation by government authorities. Sequoyah lived there at one point in his life.

The caves, which sit on private land and are now closed to the public, were used by Cherokees as places for rituals and ceremonies. Scholars said the inscriptions reflect the conflict they faced, as some Cherokees choose to assimilate and others were wanting to resist.

"This puts a definitive face on the use of syllabary and it shows us - in their own words - what the Cherokees of that time were doing," said Jan Simek, an anthropologist at the University of Tennessee in Knoxville, Tennessee. "For archaeologists, that's a remarkable outcome because you're usually interpreting symbols or words. But here they are telling us, 'We were practising in our old ways - look.' "

Deep inside the Manitou cave, experts said, is an inscription near a small creek that tells of a stick ball game, a traditional Native American game similar to but more violent than lacrosse. The game is often called the "little brother of war." An inscription there translates to "the leaders of the stick ball game on the 30th day in their month April 1828," so it's likely referring to a game that was played that day.

Cherokees typically went into a cave before a stick ball game to mentally and physically prepare themselves with a medicine man or spiritual adviser. They would cleanse themselves with water and smoke, then dance and pray.

Another inscription details the stick ball game that translates to "We who have blood come out of their nose and mouth."

Experts said that would have been indicative of Cherokee customs to re-enter the cave during an intermission or after a game. Cherokees respected that blood was a "powerful liquid" and believed such ceremonies kept the blood "outside the body from disrupting the world," according to Julie Reed, a Cherokee and historian at Pennsylvania State University who worked on the paper.

"Here we have indigenous people using a written language to tell us what they want to say," Reed said, rather than "us having to do intellectual imagination of what they're trying to tell us."

"As a Cherokee, I was like, 'Wow,' " she said of her cave visits to the inscriptions.

Some of the inscriptions are signed by Richard Guess, who was one of Sequoyah's sons and likely a ceremonial leader at the stick ball game.

Carroll, who did his master's thesis at the University of Tennessee on the cave inscriptions, said he believes the Cherokees played stick ball "just to forget, kind of entertainment and escape from the reality" around them. They were under pressure from federal authorities and Christian missionaries to end such rituals.

Another inscription in the cave was on a ceiling about 40 feet above ground. The anthropologists said it read, "I am your grandson."

Cherokees were probably sending a message to their "spiritual beings that lived here before Cherokees," Carroll said.

David Penney, an associate director for scholarship, exhibitions and public engagement at the Smithsonian's National Museum of the American Indian in Washington, said the cave inscriptions are unique from other historical finds.

"They reflect an aspect of Cherokee life before removal that's otherwise hidden or obscured from the historical record," he said.

Mr Penney said the Cherokee syllabary found in the cave is especially interesting because "history is often written by the victors. And this really is an aspect of Cherokee history that really comes from the Cherokees themselves."

For Carroll, the cave was a chance to look deep at his own people's history and see his tribe's written language in a spot where it had existed for generations. He spent three years studying the inscriptions.

"To find it like it had been since 1828" was a special moment, he said. "It was like I had just gotten there right after they left."

The Washington Post

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments