Mountain lions are elusive, looking for food, and more likely to attack if you’re moving. What’s a cyclist to do?

Mountain lion attacks remain almost surprisingly rare, but two recent dramatic incidents have shone a spotlight on the precarious human/lion balance, writes Sheila Flynn

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.The first attack came out of nowhere.

Keri Bergere and her four friends, all competitive women cyclists in their 50s and 60s, were riding along a gravel trail through a picturesque Washington forest when two mountain lions crossed their path. One of the animals kept going; the other, a 75-pound young male, unexpectedly – and terrifyingly – pounced.

The lion knocked 60-year-old Bergere off her bike and to the ground, clamping his powerful jaws around her face as it settled in for the kill, in the way that mountain lions do: Crushing and suffocating the life out of captured prey. Bergere could feel her teeth loosening and her bones crumbling as the animal held fast – but her friends sprung to action.

Grabbing large sticks, the women spent an astonishing 45 minutes tackling the lion. They attempted to pry its jaws open and even repeatedly dropping a 25–pound rock on its head, all the while petrified that its large feline companion could return. Eventually, and incredibly, the animal loosened enough that Bergere could crawl away. The cyclists pinned the lion down with a bike until the arrival of a parks and wildlife officer, who put the animal down. Bergere, miraculously, survived the 17 February attack and has lived to retell the tale as she recovers.

Another attack, however – five weeks later to the day and almost 800 miles south – did not have such a happy ending.

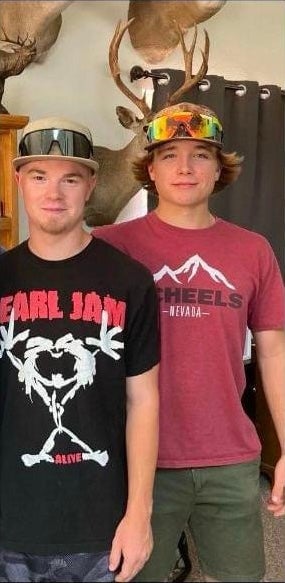

That’s when California brothers Taylen and Wyatt Brooks, seasoned outdoorsmen aged 21 and 18, respectively, were out looking for shed antlers in El Dorado County. Again, they were on a path when they encountered a lion; they tried to scare it off, following the best expert advice of yelling and waving their arms to appear bigger.

But it didn’t work; the lion charged.

At first it attacked Wyatt’s face and dragged him to the ground. His older brother was able to beat it off, but then the animal turned its attention to Taylen. The animal clamped down on the 21-year-old and wouldn’t let go, despite the frantic efforts of an injured Wyatt. The younger sibling fled for help when it became apparent his efforts to free Taylen were futile – and returning rescuers pronounced him dead at the scene.

It was the first fatal mountain lion attack in California in 20 years.

The headline-grabbing dramatic attacks, so close in time and both occurring on the West Coast, have drawn renewed attention to the dangers of mountain lion attacks— they remain exceptionally rare, but just how concerned should people be?

“Human beings are particularly vulnerable, because we’re not very fast, we don’t see very well, our hearing is really poor, relative to deer,” Utah State University’s David Stoner, a professor of wildlife ecology, told The Independent. “So one might even ask the question: Why doesn’t this happen all the time?”

Trying to predict animal instinct

Fewer than 30 fatal incidents have been recorded in North America in the past century, but the animals and imagery are evocative – fuelling everything from fear to fame. One beloved cougar, for example, captured the hearts of Hollywood during his decade-plus and widely-documented residence in Los Angeles’ Griffith Park; the collared P-22 could often be seen prowling the Hollywood Hills before the elderly cat’s 2022 euthanisation.

On the other hand, just over a year ago, former NFL player Derek Wolfe went viral for posing with a Colorado mountain lion he’d legally hunted. The Tom had been accused of killing local pets and otherwise terrorising a community, so Wolfe and a partner tracked it down and killed it with a bow and arrow. The 6’5” former Broncos defensive lineman held up the massive cat for a jaw-dropping picture; it looked as big as he did, and Wolfe estimated the lion weighed 195 pounds.

The two high-profile attacks this year have also raised questions about whether there could be some driving, common factor behind both terrifying episodes – or any explanation for the errant behaviour of predators who usually hunt alone, at night, and actively avoid human interaction.

The answer, it turns out, is probably not – though necropsy results will shed further light on whether the California cougar suffered from rabies or any condition that could fuel aggression. The Washington lion, nearly a year old, tested negative for rabies and appeared in good health, according to state wildlife officials. When it comes to attacks, it seems it’s often down to the mountain lion’s particular personality: Like humans, some are simply more aggressive than others.

“We do like to try to remember that they are individuals; they are not a uniform block of animals that always behaves the same,” T. Winston Vickers, director of UC Davis’ Mountain Lion Project, tells The Independent. “There is an individual nature, certainly, to each animal – and some are bolder, some are more aggressive but, by and large, people should certainly not think that, ‘Oh my gosh, something’s in the water.”

You have an individual animal that is a risk taker or is desperate or is simply given an opportunity that it can’t resist.

Along that vein, he compares the rarity of attacks by mountain lions – also known as cougars, pumas and panthers (yes, four common different names for the same animal) – to shark attacks.

Remind them you’re not a deer

Both of the recent strikes were by young male lions, who tend to be more curious and could be “not as successful hunting if … newly dispersed from the mother,” Vickers says. At the same time, though, studies have shown that female cougars are more likely to attack humans.

Utah State University’s David Stoner agrees that “there’s not a whole lot to draw upon other than, you have an individual animal that is a risk taker or is desperate or is simply given an opportunity that it can’t resist.”

Mule deer, as a primary food source for cougars, can often play a role here. Part of the advice for how to scare off a mountain lion – wave your arms to make yourself bigger, shout loudly, throw objects at the animal – serves a simple purpose: “To make it clear that you’re not a deer,” Vickers says.

Humans, however, are encroaching upon more and more of the habitats of both predator and prey as urban sprawl expands throughout the West. Stoner says he’s previously discussed a monitoring project with California authorities centred on the exact area where the brothers were tragically attacked last month. El Dorado County, he tells The Independent “is a very rapidly growing county” that’s become “a hotspot for conflicts with mountain lions”, though that’s usually centred on goats, sheep and livestock, not people.

The climate crisis impact

While it doesn’t seem to be an immediately obvious factor in the recent attacks, any dip in availability of deer as a food source can, undoubtedly, influence the animals’ behaviour.

In parts of the West, for example, the harsh winter “that ended a year ago was extraordinary,” Stoner says, including near his home “right about where Utah, Idaho and Wyoming come together.”

There were “huge die-offs of mule deer because of deep snows,” with the marked fawn survival rate on the management unit adjacent to the university at zero per cent last year, he says.

“Fawns are a major food resource for mountain lions, particularly the young, young animals that are not really good hunters yet – and for the females that have dependent kittens,” said Stoner. “This year, that whole cohort is missing. We also had very low adult survival. So there’s just less game on the landscape now than there was two years ago. Is this related? I can’t say.”

Studies have shown that wildfires can change mountain lion patterns, too – and both El Dorado County and the region of the Washington State cyclist attack have suffered fires in recent years.

That’s because wildfires decrease vegetation and wildlife, and therefore mountain lions are out and about looking further afield for food. Wildfires “increased behaviours associated with anthropogenic risk, including more frequent road and freeway crossings … and greater activity during the daytime (means from increased 10% to 16% of daytime active), a time when they are most likely to encounter humans,” researchers wrote in a paper published in the November 2022 issue of Current Biology, which looked at post-fire responses of a small sample of lions in Southern California. The paper also noted an increase of cougar space used and distance travelled post-fire.

But much that is known about mountain lions remains essentially guesswork, given how elusive they are.

“I’ve been studying these critters in the field for over 25 years, and I can count on one hand the numbers I’ve seen” them without tech tracking assistance, Stoner says.

According to the Mountain Lion Foundation, state game agencies have estimated mountain lion populations in the US to be between 20,000 and 40,000. Adult males usually weigh between 110 and 180 pounds, with females falling between the 80 and 130-pound range.

They’re kind of scaredy cats when it comes to how they react to people.

The animals can be legally hunted in 13 Western states; California has banned the practice unless a cougar has harmed pets or livestock.

“A couple centuries of persecution” may have prompted the lions’ evolutionary tendency to avoid humans, according to Vickers, the Mountain Lion Project’s lead wildlife veterinarian.

“We would be in deep doo-doo if they had the behaviours of, say, leopards or tigers or something and inclinations to see us as prey,” he says. “But they so rarely do. They’re kind of scaredy cats when it comes to how they react to people. When they do encounter them, they almost always just take off – either sneak away or run away or walk away, but they definitely try to go somewhere else.”

How to avoid attack

Despite that, however, there are various conditions that do increase the likelihood of human/lion conflict – and there are steps that can be taken to avoid it. Experts, poring over more than 100 years of documented attacks, published a comprehensive 2011 paper in scientific journal Human-Wildlife Interactions which found that simple things such as the presence of a dog can greatly reduce risk.

Alternatively, women and children were more likely to be pounced upon, given their smaller stature, as were victims in motion – like cyclists. In Washington State, in the same county as the February attack, a 3-year-old male mountain lion killed one 32-year-old and injured the victim’s companion in May 2019 when the pair were mountain biking along a dirt road. In that tragic case, the cyclist killed had also taken off running, which experts warn against.

“People who were moving quickly or erratically when an encounter happened (running, playing, skiing, snowshoeing, biking, ATV-riding) were more likely to be attacked and killed compared to people who were less active (25% versus 8% fatality)” the authors wrote. “Children (<10 years) were more likely than single adults to be attacked, but intervention by people of any age reduced odds of a child’s death by 4.6x.”

Mountain lions, as mentioned, usually hunt alone and at night – and stealthily, Stoner says.

“What they will try to do is get as close as possible, a short rush, and then grapple the victim and bite to the neck or bite to the muzzle, sometimes to the top of the head, but usually on the back of the neck, the throat, or the muzzle,” he tells The Independent. “And the objective is to subdue the animal as quickly as possible, because a struggling animal that’s desperate and fighting for its life is very dangerous.

“But they will also adopt a hunting strategy in which they wait by a game trail or someplace with a lot of traffic and just wait for an opportunity,” he says. “So that’s where I think mountain bikers and hikers may be more vulnerable … they are in the wrong place at the wrong time.”

To avoid attacks, in addition to bringing dogs along, Vickers recommends carrying protection.

“Some people in some states are more likely to be carrying guns, but, for the average hiker, I think bear spray and a good hefty walking stick are a pretty good combo,” he says. “And I’ll throw out one other thing: Some people carry air horns, especially because sometimes, when a mountain lion is just sort of in that intensively interested stage, then having some other way to make intense noise that would not only startle them out of that maybe interested situation, but also alert other people could also be helpful.”

The Washington cyclists, for one, will be following that advice.

“We’re all going to carry a weapon, a knife, you know, because you can’t kill a cougar with sticks and stones,” Bergere, who spent five days in the hospital after the attack, told NPR last week.

“I am alive,” she continued. “I’m grateful and happy to be here and grateful to my ladies that are now my family.”

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments