Hopes and fears on the migrants’ bus bound for a new life in America

People from Central America are boarding buses in Texas to cities across US, writes Andrew Buncombe in Brownsville

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.They face a long bus ride before reaching their final destination, perhaps several.

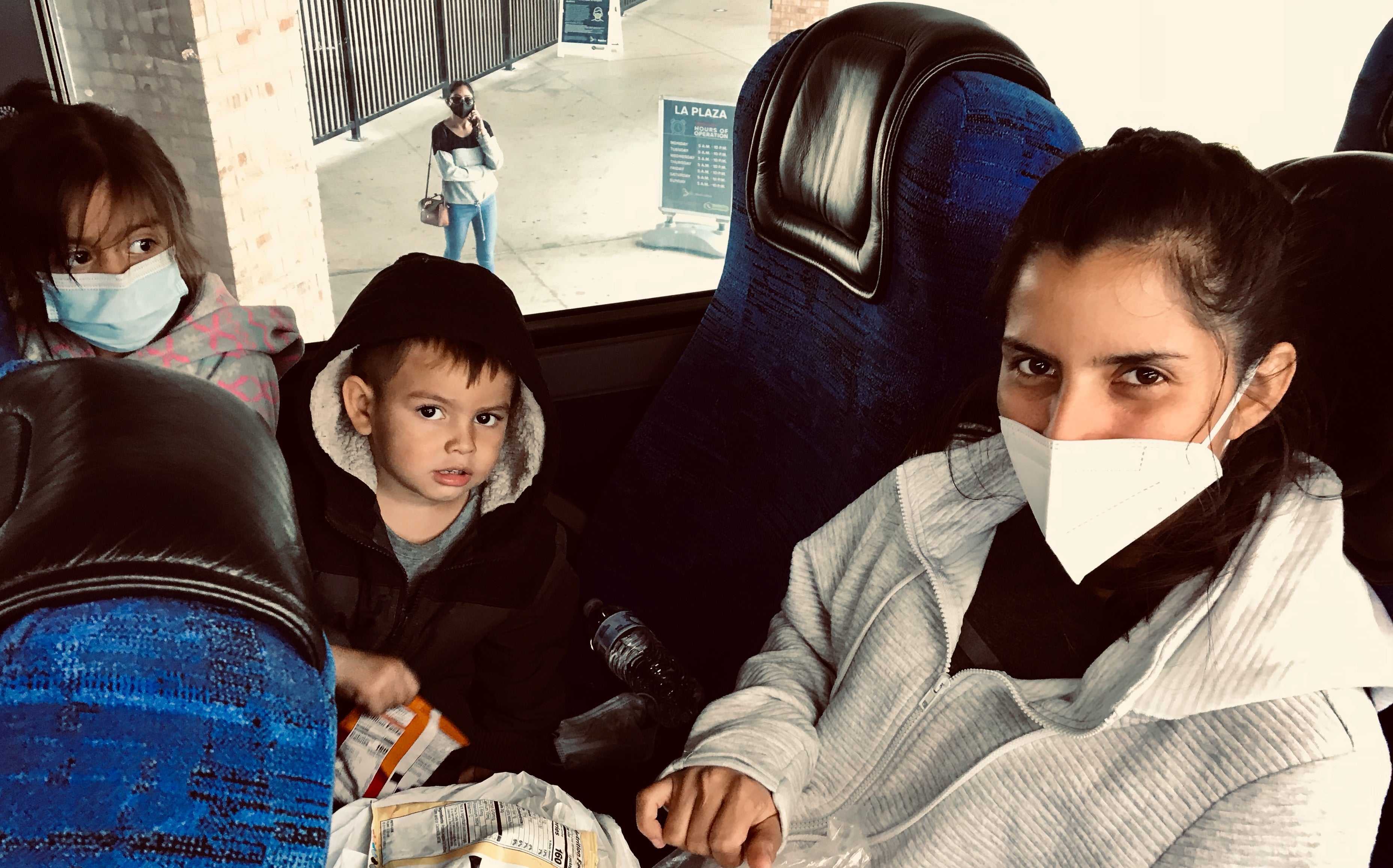

But after what Karina Aguirre and her two children had been through this last month to get here, it is clear that will not stop them.

The 23-year-old from Suchitepéquez, a southwestern region of Guatemala, paid $10,000 to a coyote (people smuggler) and spent 45 days walking and riding in buses and trucks, before they were able to enter the US.

Now, her eyes flash as she ponders the prospect of a new life for her and her youngsters, and the chance to reunite with her mother, who left when she was five.

“It was a difficult journey,” she says. “I will be happy to meet my mother. And for her to see my children.”

In the last few weeks, as hundreds of migrants have entered the US, many of them taking the opportunity presented by changes enacted by Joe Biden, who was determined that the most vulnerable seeking asylum should have their cases determined while waiting in the US rather than Mexico, the bus station in Brownsville has acted as both a transport hub and makeshift processing centre.

Every day scores, if not hundreds, are dropped by Customs and Border Patrol agents. And hundreds board buses bound for cities such as as Dallas and Houston. From there, many will change buses and meet up with relatives in places such as Indiana and Florida.

Aguirre is heading to Florida where her mother lives, and where she hopes she can find a new start, a proper job for herself, and school for her children, a daughter and a son.

“I want to find a proper profession,” she says. “In my country, there is so much poverty, and violence.”

The bus station, more properly La Plaza at Brownsville Terminal, is an elegant structure, styled on architecture of a previous century, and is edged by palm trees. Today, the area where people wait for the buses – not the air-conditioned interior – is packed with people such as Aguirre.

Many are sleeping on the floor, or resting on seats, their eyes often dropping shut as though they were weighted with heavy stones. Everyone appears ready for a good long sleep.

Alonzo Edgardo, 35, is with his wife, Miralda, and two-year-old son, Kelvin, and came from El Salvador. “There are too many problems there, and the pandemic has made it worse,” he says. “Right now, there are no vaccines. And there are no jobs.”

They are scheduled to travel to New Jersey, where their sponsor, his wife’s aunt, lives. They do not know how long the bus ride will take, and seem less than delighted when they are told it will take them no small time to get where they are going.

To help them arrive in better health, and with some degree of comfort, charities such as Team Brownsville, and the city government, have been working to provide food, clothes and other essentials.

The city has also contracted with a clinic to carry out Covid testing. “The number of people testing positive is very low. Less than one per cent,” says a nurse, who asks not to be named. “The children are a little nervous. But the adults are fine with it.”

Javier Guajardo, who usually works for Good Neighbour Settlement House, a homeless charity, is overseeing the efforts of volunteers who provide the migrants with backpacks filled with a blanket, snacks and toiletries. “It can get cold on the buses.”

Cindy Claudia works with a group of mainly women, known as the Angry Tias and Abuelas of the Rio Grande Valley, that operates on both sides of the border to help those in need.

She says some of the volunteers refer to the bags and items as “Dignity Packs”. “They contain some toiletries, but we are trying to give these people back their dignity, which has been taken away by the way our government has treated them,” she says.

Almost all of the migrants are from Central America, though volunteers say a number of those arriving at the border in recent days and weeks set off originally from Cuba.

The decision by the Biden administration means officials have been releasing many migrants before they have court dates for their asylum cases. Individuals are required to contact the authorities when they arrive at their relatives’ home.

The update in arrivals, something that has spiked several times since 2014, often in response to political changes in the US, has created the first major test for Biden, who was elected vowing to oversee a more humane immigration policy than Donald Trump.

On Thursday, at his first official press conference since becoming president, he defended his policies and denied claims that his comparatively softer attitude was encouraging more migrants.

“It happens every single, solitary year. There is a significant increase in the number of people coming to the border in the winter months of January, February, March. It happens every year,” he said. “By the way, does anybody suggest that there was a 31 per cent increase under Trump because he was a nice guy? And he was doing good things at the border? That's not the reason they’re coming.”

Donal Jose Valle says the reason he has come to the US has nothing to do with Biden, or the time of year.

Rather, the 36-year-old says he, his wife and two children from Managua, in Nicaragua, set off on a journey that took them 36 days, because of the situation in their own country.

In Nicaragua, President Daniel Ortega is likely to seek another term in November, despite growing disquiet. In 2018, more than 100 people were killed in clashes with the police.

Last month, the UN high commissioner for human rights, Michelle Bachelet, said new laws adopted by Nicaragua’s government were undermining fundamental freedoms.

“My office has documented 117 cases of harassment, intimidation and threats by police officers or pro-government elements against students, peasants, political activists, human rights defenders and organisations of victims and of women,” she said.

Valle is emotional as he explains why he has had to leave. The situation has become steadily worse, he says. “Ortega is now like a dictator, like Somoza,” he says, referring to Anastasio Somoza Debayle, the late dictator ousted by Ortega and his Sandinista rebels in 1979. He was assassinated the following year in Paraguay.

Aguirre is traveling first to Houston on a pale blue bus, operated by the El Expreso Bus Company. The driver is Alejardo Saldana. He says in the last few weeks, he has been driving hundreds of migrants as they embark on new lives, new beginnings. “It is very good for these people,” he says.

Aguirre’s bus is due to leave at 11.30am, and as the departure time nears, a queue of travellers line up, tickets in their hands.

The young woman and her children take a seat on the upper desk, not far from the front, the youngsters looking out of the glass. At 11.40am, Saldana takes his seat, reverses the bus out of the bay, and the gate to the terminal swings open to let him pass.

There are some waves from the passengers, and then the bus is gone.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments