Michael Brown shooting: Forensic evidence supports officer's version of events that sparked Ferguson riots

Some physical evidence - including blood spatter analysis, shell casings and ballistics tests - supports officer Darren Wilson's account

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Ferguson police officer Darren Wilson and Michael Brown fought for control of the officer’s gun, and Wilson fatally shot the unarmed teenager after he moved toward the officer as they faced off in the street, according to interviews, news accounts and the full report of the St. Louis County autopsy of Brown’s body.

Because Wilson is white and Brown was black, the case has ignited intense debate over how police interact with African American men. But more than a half-dozen unnamed black witnesses have provided testimony to a St. Louis County grand jury that largely supports Wilson’s account of events of 9 August, according to several people familiar with the investigation who spoke with The Washington Post.

Some of the physical evidence — including blood spatter analysis, shell casings and ballistics tests — also supports Wilson’s account of the shooting, The Post’s sources said, which casts Brown as an aggressor who threatened the officer’s life. The sources spoke on the condition of anonymity because they are prohibited from publicly discussing the case.

The grand jury is expected to complete its deliberations next month over whether Wilson broke the law in confronting Brown, and the pending decision appears to be prompting the unofficial release of information about the case and what the jurors have been told.

The St. Louis Post-Dispatch late Tuesday night published Brown’s official county autopsy report, an analysis of which also suggests that the 18-year-old may not have had his hands raised when he was fatally shot, as has been the contention of protesters who have demanded Wilson’s arrest.

Experts told the newspaper that Brown was first shot at close range and may have been reaching for Wilson’s weapon while the officer was still in his vehicle and Brown was standing at the driver’s side window. The autopsy found material “consistent with products that are discharged from the barrel of a firearm” in a wound on Brown’s thumb, the autopsy says.

Judy Melinek, a forensic pathologist in San Francisco who reviewed the report for the Post-Dispatch, said it “supports the fact that this guy is reaching for the gun, if he has gunpowder particulate material in the wound.”

Melinek, who is not involved in the investigation, said the autopsy did not support those who claim Brown was attempting to flee or surrender when Wilson shot him in the street.

Victor W. Weedn, chairman of the George Washington University Department of Forensic Sciences, said the autopsy report raises doubts about whether Brown’s hands were raised at the time of the shooting but is not conclusive.

“Somebody could have raised their hands way above their head and lowered their hands and then be shot,” Weedn said. “So an autopsy will never rule out that the hands were above the head. It can only say what happened at the time of the shooting. . . . With the graze to the right arm, it appears the arm was in a vertical position, suggesting that it was closer to down by his side, but it could have been higher.”

Benjamin L. Crump, an attorney for the Brown family, said Brown’s family and supporters will not be convinced by the autopsy report or eyewitness statements that back Wilson’s account of the incident.

“The family has not believed anything the police or this medical examiner has said,” Crump said. “They have their witnesses. We have seven witnesses that we know about that say the opposite.”

Crump also said one of the reasons the family and protesters were opposed to a grand jury proceeding was because it gives authorities too much control over what the public learns about the case, as evidenced by the leaks.

“The family wanted a jury trial that was transparent, not one done in secrecy, not something that they believe is an attempt to sweep their son’s death under the rug,” he said.

Wilson’s attorney, James P. Towey Jr., did not return a call seeking comment.

Seven or eight African American eyewitnesses have provided testimony consistent with Wilson’s account, but none have spoken publicly out of fear for their safety, The Post’s sources said.

The St. Louis County Police Department and the FBI are investigating the shooting, and evidence gathered by both agencies is being presented to the grand jury, which started meeting in mid-August and is expected to conclude its work early next month.

The evidence the grand jury is reviewing is voluminous. From the beginning, St. Louis County Prosecuting Attorney Robert McCulloch decided jurors would hear and review all credible and reliable evidence, including testimony from each eyewitness.

Jurors have also seen the St. Louis County autopsy report, including toxicology test results for Brown that show he had tetrahydrocannabinol, the active ingredient in marijuana, in his system. The Post’s sources said the levels in Brown’s body may have been high enough to trigger hallucinations.

The county police, the FBI and the Justice Department all declined to comment on the information The Post received regarding testimony and evidence in the case.

“The independent federal investigation into the shooting of Michael Brown is ongoing,” said Dena Iverson, a Justice Department spokeswoman. “We will not comment on irresponsible leaks and rumors about the status of the investigation.”

She added later Wednesday that “there seems to be an inappropriate effort to influence public opinion about this case.”

Tim Fitch, a former St. Louis County police chief, said there are benefits to leaking crucial information to the public ahead of a grand jury announcement.

“I think it’s good to get some accurate information out there. That way on game day, it’s not a surprise to people,” said Fitch, who retired last year from the county police department, which is conducting the investigation into Wilson’s actions.

Ed Magee, McCulloch’s spokesman, said the leaks won’t stop the deliberations. “We will continue to present evidence to the grand jury, and our office is not responsible for these leaks,” he said.

During his testimony before the grand jury last month, Wilson told jurors that the encounter with Brown and his friend Dorian Johnson began when he ordered the two men to stop walking in the street and get onto the sidewalk, The Post’s sources said.

Things quickly escalated, Wilson told jurors, with Brown shouting an expletive at him and refusing to move to the sidewalk, The Post’s sources said. In August, an attorney for Johnson said the officer used profanity when ordering the two onto the sidewalk.

The Post’s sources interviewed in recent days said Wilson testified that he stopped his police SUV and opened the door to approach Brown, but the 18-year-old used both hands to slam the door shut, trapping him in his patrol vehicle. Brown then reached through the open window and began to repeatedly punch the officer in the face, Wilson testified.

The officer said he reached for his gun to defend himself, but Brown grabbed it and let go only after it fired twice. Two casings from Wilson’s gun were recovered from the police SUV, the sources said.

After he was shot in the altercation at the vehicle, Brown fled with Johnson, and Wilson testified that he ordered Brown to stop and lower himself to the ground. Instead, Brown turned and moved toward the officer, the sources said. Wilson said he feared that Brown, who was 6-foot-4 and weighed nearly 300 pounds, would overpower him, so he repeatedly fired his gun.

Brown was shot at least six times, according to all three autopsies that have been conducted.

The Post-Dispatch, in a story on Wilson’s account of the incident published early Wednesday, cited a single “source with knowledge of his statements” in providing additional details. The story said Wilson testified that during the struggle at the SUV, Brown pressed the barrel of his gun against the officer’s hip and attempted to prevent Wilson from reaching the trigger. According to Wilson’s testimony, the Post-Dispatch said, Brown was running toward Wilson when he was fatally shot and his hands were not up.

The source also told the newspaper that Wilson told jurors he was trapped in the front seat and could not use his pepper spray to subdue Brown because the officer would have also incapacitated himself. His baton was also out of reach, at the back of his utility belt, pinned between his body and the seat. He also did not have a stun gun, so he drew his gun, the Post-Dispatch reported.

The autopsy says that Brown was shot in the forehead, twice in the chest and once in the upper right arm. The fatal wound to Brown’s head indicates that he was leaning or falling forward, and the path of a sixth shot, which hit Brown’s forearm and traveled from the back of his arm to his inner arm, means that Brown’s palms were not facing Wilson in an act of surrender, according to analysts cited by the Post-Dispatch.

In interviews with The Post, sources said blood spatter evidence shows that Brown was heading toward the officer during their faceoff, but analysis of the evidence did not reveal how fast Brown was moving.

According to Johnson, after Wilson ordered the men out of the street, he put his vehicle in reverse and opened the front door so forcefully that it bounced against them.

Johnson has said that Wilson, while still in the SUV, grabbed Brown by his collar. Brown was trying to free himself and never tried to get the gun, Johnson said. Wilson drew his gun and threatened to shoot, then it went off, he said. Johnson and Brown then ran.

“He shot again and once my friend felt that shot he turned around and put his hands in the air and started to get down, and the officer still approached with his weapon drawn and fired several more shots,” Johnson told CBS News in an interview.

Several other witnesses gave interviews to the news media saying they saw activity at the vehicle, but each said they were unclear about the nature of that encounter. They have offered varied though fundamentally similar versions of what happened afterward. Brown, witnesses said, was fleeing when Wilson opened fire on the street. After being hit by a bullet, Brown turned around with his hands up, trying to surrender, when the officer shot him several more times, they said.

How high Brown’s hands were has been inconsistent in accounts, and at least one witness said that after Brown was shot, he appeared to take a step toward Wilson. That witness said, however, that Brown had his arms around his stomach before hitting the ground.

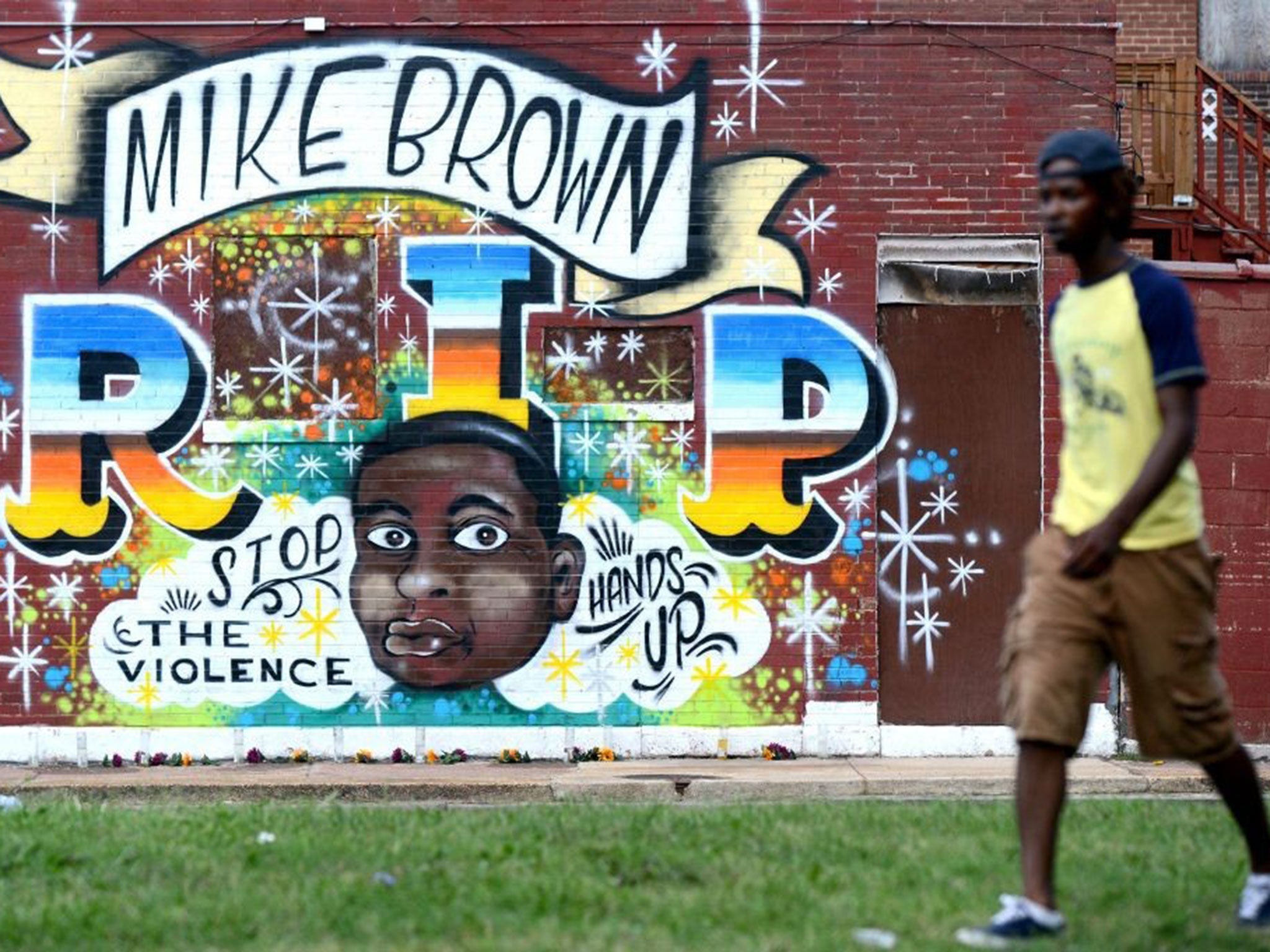

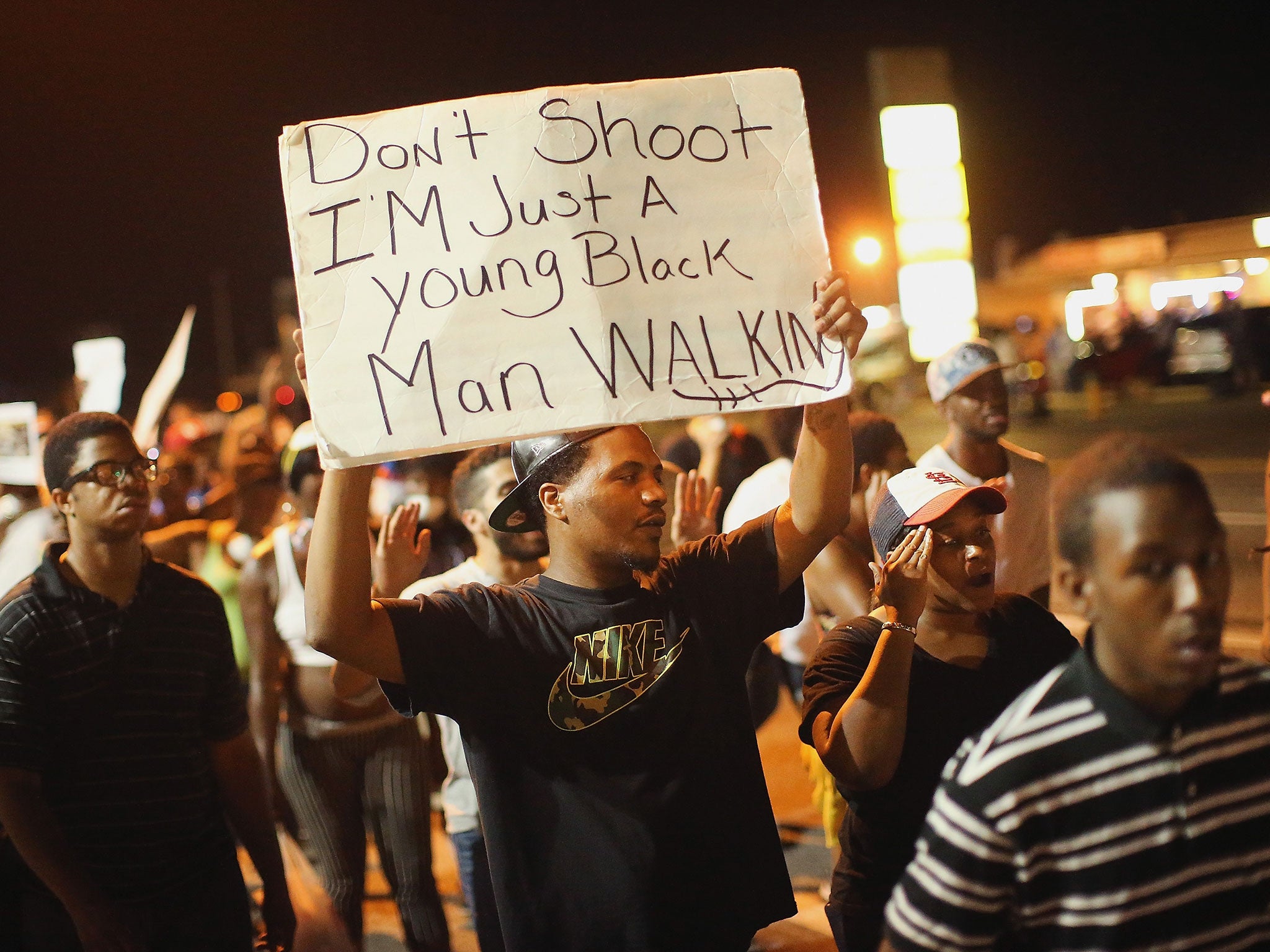

Protests erupted after the shooting, and demonstrators squared off against police who used tear gas and rubber-coated bullets to try to disperse crowds. Images of police patrolling the streets and clashing with demonstrators at night shocked many and drew concern from the White House and some Washington lawmakers.

The grand jury proceedings are unusual. Typically in a grand jury case, the lead investigator will provide an overview of his findings and perhaps one or two witnesses will testify.

However, McCulloch decided from the beginning that the grand jury in this case would sort through all the evidence. And, instead of telling grand jury members what charges they believe Wilson should face, prosecutors are involving the grand jury as co-investigators.

©Washington Post. Justin Moyer, Lindsey Bever and Alice Crites contributed to this report.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments