An 1851 maritime law protected the Titanic’s owners in court. Could OceanGate use it too?

The owners of Titanic sought to limit liability following the ship’s sinking by petitioning under 1851 legislation. The owners of the submersible lost on its dive to visit that famed ship’s wreckage may do the same thing, legal experts tell Sheila Flynn

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.The company operating the ill-fated Titan submersible could attempt to avoid legal liability by taking advantage of the same law used by the owners of the doomed Titanic more than a century ago – in a tragically macabre full-circle development, according to legal experts.

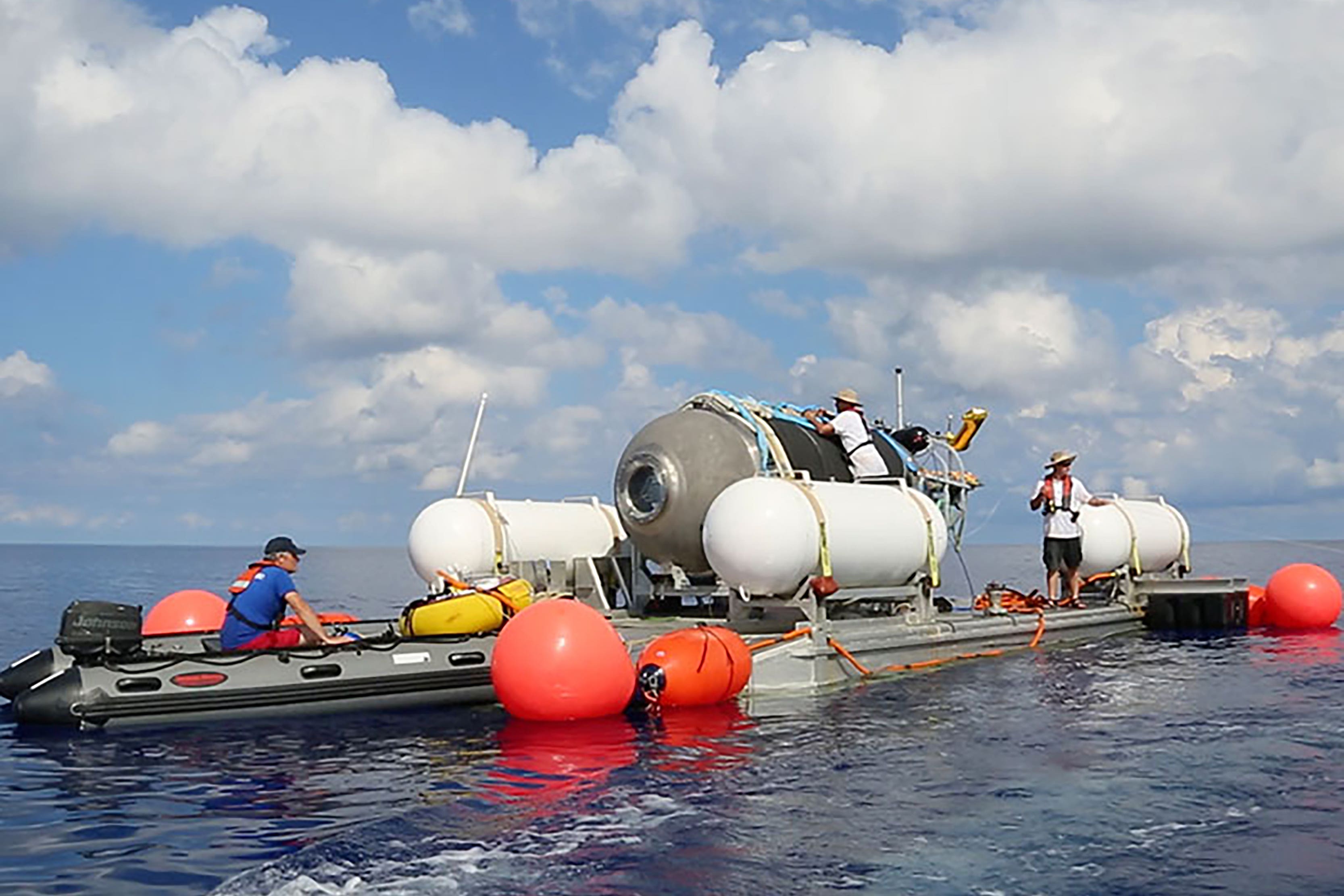

A five-day search for OceanGate Expedition’s tourist submersible came to a grim conclusion when officials confirmed the discovery of debris consistent with a “catastrophic implosion” presumed to have claimed the lives of all five passengers. Days later, the US Coast Guard confirmed “presumed human remains” had been recovered from the sea floor and debris from the vessel was seen being returned to dry land in Canada.

With investigations now underway into what went wrong, focus has turned to whether and how OceanGate could be held liable in court. Experts tell The Independent that one 172-year-old piece of legislation could prove pivotal for the company: the Limitation of Liability Act of 1851.

“It is an interesting situation because of where it happened in international waters – there's a lot of complex issues of choice of law and jurisdiction about where any disputes may take place, what companies or what entity and government authorities will investigate,” Tulane University adjunct maritime law professor Michael Harowski, who teaches a course at the renowned institution’s law school on limitation liability, tells The Independent.

“It’ll be fascinating to see how it plays out, because actually, going back to the original Titanic disaster, that raised a lot of the same concerns and issues as to liability – and, in fact, the owners of the Titanic in the United States did seek protection under the limitation of liability.”

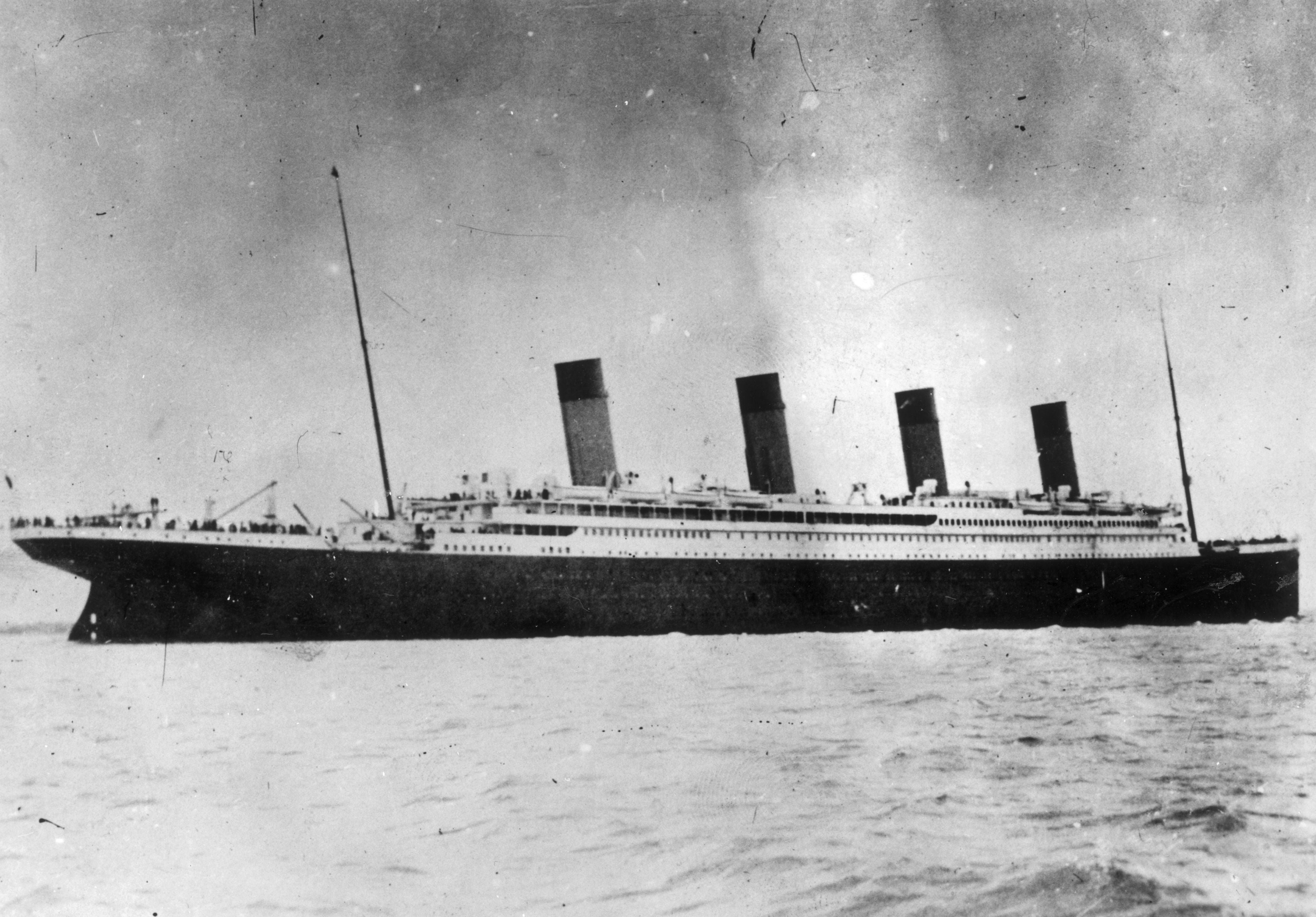

The Titan is believed to have imploded on Sunday morning while carrying five men to the gravesite of Titanic – which sank in April 1912, killing more than 1,500 people aboard. The passengers were: OceanGate CEO Stockton Rush; French diver Paul-Henry Nargeolet; British billionaire Hamish Harding; and Pakistani businessman Shahzada Dawood with his 19-year-old son, Suleman.

Previous expedition participants have described signing extensive waivers accepting the possibility of injury or death on the Titan – but the victims’ families are still expected to pursue damages against OceanGate.

The question of seaworthiness

“Any claimants will most likely proceed, at least in part, under the Death on the High Seas Act (DOHSA),” Maritime Law Hawaii’s Andrew Porter, who will be teaching a course this year at the University of Hawaii’s renowned law school, tells The Independent in an email. “The two aspects of this case that immediately come into focus are the seaworthiness of the vessel and the loss of future income of the deceased.”

Allegations of potential safety issues with the Titan emerged early in the search. Troubling accounts of whistleblower warnings, “experimental” design practices and unreliable communication systems on the vessel came flooding out through employee lawsuits, a letter from maritime industry leaders, and comments from the company’s CEO Stockton Rush.

Mr Porter declined to comment on those claims “due to a lack of personal knowledge”. But, he says: “The seaworthiness of the vessel and any alleged negligence of the owner will be the heart of any lawsuit that comes before the courts. Under maritime law, an owner has an absolute duty to provide a seaworthy vessel for the crew and any passengers.”

He explains that seaworthiness is roughly defined as “whether the vessel was fit for its intended purpose and voyage”.

“Thus, the crux of any plaintiff’s case will be the design and testing of the vessel, whether the vessel met the required regulations for a commercial voyage, and whether the vessel was reasonably maintained, supplied, and crewed to undertake the voyage,” he says. “A caveat to this is that under the ‘seaworthiness’ questioning, unlike negligence, a plaintiff is not required to prove that the owner had prior knowledge of the defect, maintenance, or design flaw that gave rise to the incident – the presence of such defect alone can in many cases give rise to liability.”

But archaic maritime laws may afford OceanGate the possibility of escaping some culpability in the courts going forward — just as the White Star Line attempted to do after its prize ship, the RMS Titanic, hit an iceberg and sank 110 years ago.

Limitation of liability

“There’s entire sections of the federal code that are maritime law, and probably the most important one, for our purposes, is the 1851 Limitation Act,” Fordham Law School Professor Lawrence B. Brennan tells The Independent. “If you’re a defendant, and your car has an accident and damages property or kills somebody or injures them, you can't limit your liability. You either are exonerated, there’s an allocation of fault, or you pay the full damages. In Admiralty [maritime law], the shipowner defendant can start a proceeding where it chooses, within certain limits, and argues that it's not responsible for anything. And that goes back to the 1851 statute.”

At the time the legislation was brought in to avoid shipping company bankruptcies, Prof Brennan says, “there were no steel ships to speak of, and they were mostly steam ships, and there were a lot of fires — so a law that precedes the Lincoln administration causes some interesting litigation.”

An OceanGate petition under the act would “attempt to limit their liability to the post-casualty value of the vessel, which is zero,” he says of the imploded Titan. “Plus, in injury and death cases, a certain tonnage amount, which will be relatively small for the dead and injured.”

Prof Brennan continues: “It’s one of these bizarre things where the nominal defendant can commence an action. It’s more akin, intellectually, to a bankruptcy proceeding; it’s not procedurally akin, it’s a pure admiralty thing. One of the major cases in there, surprisingly, is the SS Titanic.”

He predicts that the company will argue: “We’re not liable, and if we’re liable, we exercised due diligence, and the standard in death cases is broader than property damage cases, and we owe no one anything.”

The 1851 legislation was amended just last year, however, in response to a 2019 small vessel fire in California — and legal action related to Titan’s demise may fall within the parameters of that new Small Passenger Vessel Liability Fairness Act, Tulane’s Prof Harowski, who is also a partner at law firm Wilson Elser’s New Orleans office in the Admirality & Maritime practice, tells The Independent.

“They changed the law to exempt small passenger vessels from the scope of the limitation of liability,” he says, adding that “there’s not much good law out there about small passenger submarines.

“I think there's a chance that this ... could fall within the scope of this act, so that OceanGate may not be able to limit their liability because of this new congressional amendment to the data.”

Nothing is certain, however, and he admits that the “Limitation Act is still very much in use, and there are some requirements for limiting the liability under it, namely that the owner of the vessel can't have any knowledge of the cause of the [tragedy] prior to [it].

“If evidence comes out that OceanGate knew of some design flaw or risks, and then went ahead with it anyway, that might prevent them from limiting their liability anyway, even if it wasn't exempt under the Small Vessel Liability Act.”

It has emerged that a 2018 lawsuit brought by OceanGate’s former director of marine operations accused the company of ignoring safety concerns — and questions have been raised about Titan’s design and material choices. Such concerns were repeatedly dismissed by OceanGate’s CEO Mr Rush.

Beyond the questions of seaworthiness and use of the Liability Act, there’s the issue of what the law might consider a submersible in the first place.

“It’s unusual in that it, obviously, it's a submersible, and I'm not aware of any other similar instances involving submersible,” Prof Harowski says. “But, legally, I'm not sure that changes that drastically. It's still a vessel.”

That being said, there are no clear-cut precedents to look to here, and all of the uncertainties — particularly jurisdiction — will hugely affect what happens next.

“It’s a device; it’s obviously not a vessel to go on the surface of the water ... as I understand, the Titan itself was not registered with any country, so it was not flying any flag, and so it's kind of wide open,” University of Washington Professor Tom Schoenbaum, author of Schoenbaum’s Admiralty & Maritime Law, tells The Independent.

Criminal proceedings

Prof Schoenbaum says he thinks it “very unlikely” that criminal proceedings will arise — but draws a distinction between three different types of actions going forward.

“Number one would be the liability, actions filed by the estates of the passengers,” he says. “Number two, there's the regulatory aspect, whether the Titan broke any regulatory. And specifically, the US will be involved in that, because OceanGate is a Washington state company, headquartered in Everett, Washington.

“As far as US law is concerned, there's a requirement that a submersible — there's a 1993 act — that the Coast Guard says applies to submersibles capable of carrying one passenger. This obviously would qualify. And it requires certification by an industry standard group, and I don't think that this Titan had any certification, or maybe if they did they had a certification by a substandard certifying body.”

If certifications were found to be lacking, he says, the company would “certainly face fines” — and that’s separate from a third type of proceedings: Insurance probes.

The complicated and unprecedented circumstances mean that many questions remain about what can and will happen — and, importantly, which jurisdiction(s) consequences will be happening in.

“The investigation probably is going to be Coast Guard, National Transportation Safety Board ... the Justice Department will get involved if there’s criminal proceedings worth investigating,” he says, adding that officials could still “come up with a clean bill and say, you know, no one’s responsible.”

There is a long-shot possibility of state action, depending on the waters involved, and Prof Brennan names authorities in Canada, the US and maybe France as “the obvious probable investigating bodies”.

“Will they agree to do joint investigations or share it? I hope so,” he says. “It would be some efficiency and some cost savings ... I think that we’re going to have to have different authorities, and we’re going to have different authorities with different standards and different protection against self-incrimination and corporate liability, and we can have multiple proceedings and the same facts in different countries. Not going to surprise me.”

Depending upon the findings of any investigations, charges could include negligent “homicide. negligent preparation, operation of the vessel; people who are not properly licensed,” Prof Brennan says, cautioning: “I’m just giving you a checklist, not saying there’s anything there, of course.”

He predicts that any “trial is going to be a nightmare” while pointing out: “90 per cent of federal civil litigation, including admiralty cases, settle.”

Settlement possibility

He believes any case involving Titan will also settle “eventually, probably”.

“But it depends on what discovery shows,” he says. “And, the more facts that come out, and the more problems that can be argued, the harder it's going to be for the ship owner to settle. And if the [victim] estates have weak cases, are they going to take nominal settlements? And that's what it's going to come down to and ... we're going to deal with this for a long time.”

OceanGate did not respond to The Independent regarding whether it has petitioned under the 1851 Act, referring only to its earlier statements on the ordeal.

More than a century ago, however, the owners of Titanic were able to successfully limit their liability against claims under the act. However, they had to defend claims brought in the United Kingdom separately, Prof Harowski says, noting that the “UK applies a totally different legal regime for limitation of liability.”

And, as Prof Schoenbaum points out, much of OceanGate’s liability may rest with the content of the waivers signed by those on board.

“The wording of those waivers of liability will be very important, but they may well be valid,” he says. “Because it is against public policy to, for example, if you're on a cruise ship, the cruise ship cannot make you sign any waiver of liability.

“But on an experimental trip like this Titan, those people knew what they were getting into. And my feeling is that these waivers of liability would be upheld in the US courts.”

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments