Why losing trans pioneer Lynn Conway feels like a death in the family

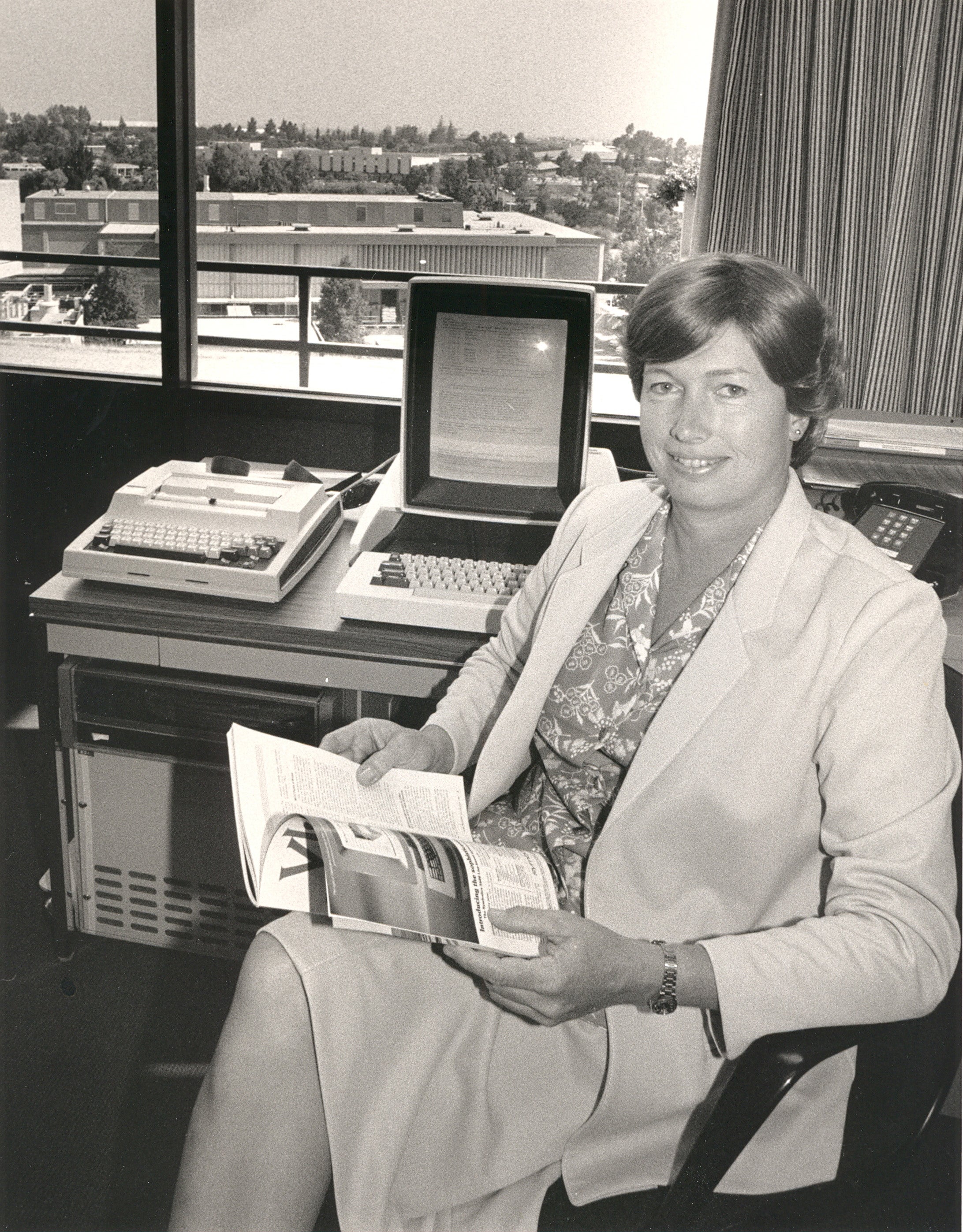

To Silicon Valley, Lynn Conway was the co-inventor of a microchip revolution. But for transgender people, she was also part of the fragile thread that links us to our history, writes Io Dodds

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.There is part of me that will probably always feel like an orphan.

Don’t get me wrong, my parents are perfectly alive. I love them very much, and I’m lucky enough to have a good relationship with them. But there’s still a part of me that they could never parent, never fully nourish, because they didn’t know it existed.

How could they, given that not even I myself knew? This was the Nineties and early Noughties, when transgender people were rarely discussed, except perhaps as bad jokes or "inspirational" yet distant objects of curiosity.

For trans people my age (I’m 35), I think this is a common feeling. Even if we grew up safe and loved – which far too many of us did not – there was a secret, vital part of our souls that remained cut off from caregivers, grandparents, mentors, and role models.

And so, when we finally got free, we had to go and seek our own.

Lynn Conway died last Sunday at the age of 86, after a long life at the heart of two revolutions. One was the computer revolution, which she helped accelerate by co-inventing a new method of microchip design that is now used in everything from your car to your smartphone.

The other was the transgender revolution, which Lynn joined in a quieter way in 1967 when she began transitioning from (as people used to put it) male to female. Decades later, she came out publicly and became a vocal advocate for trans rights.

Her site wasn’t the first one I found. But when I did find it, it opened a whole new world to me. I knew I wasn’t alone.

I’d been aware of Lynn ever since I was a young teenager, adrift on the dark ocean of the early internet. At some point I’d stumbled across her personal website: a classic Web 1.0 number containing not only her life story but a treasure trove of information on gender transition, from a hero’s gallery of trans successes to a frank and detailed discussion of how to get a vaginoplasty (and how to relearn having sex afterwards).

For some people, the information it provided was life-changing. "Her site wasn’t the first one I found," says Rebecca, a 51-year-old government worker in Colorado. "But when I did find it, it opened a whole new world to me. I knew I wasn’t alone."

I’d love to say that Lynn’s website had a similar effect on me, and spurred some crucial awakening. In truth, I wasn’t ready yet. I guess I thought something like: "Wow, that’s so cool! I find this fascinating for some unknown reason that I’m too scared to investigate right now.”

Lynn remained an inspiring figure to me 20-odd years later, long after I’d realised the error of this strategy and embarked upon what in her day was rather excitingly known as a "sex change". So I was thrilled when she agreed last year to be profiled by The Independent — and we spent hours on Zoom and phone calls, laughing and talking deeply about life, trauma, technological change and the forces that shape history.

Interviewing Lynn was a bit of a rollercoaster. Often she’d gaily embark on what seemed to be a wild tangent, leaping sideways through apparently unconnected topics, until finally thirty minutes later she’d circle back around and you’d understand that actually it wasn’t a tangent at all. As a journalist, it was continually frustrating. As a human being, it was exciting and a little dizzying.

There’s a meme that compares "talking about gender with trans people" (Greek philosophers discoursing in the agora!) to "talking with gender about cis people" (pushing plastic toys around with a vexed-looking toddler). Imagine that, but also the other trans person is 85 years old and a renowned expert on computer architecture and theories of innovation.

She told me about the "haunted" world she grew up in, where everyone pretended not to see the violence beneath the veneer. About the electrifying effect that stories like Christine Jorgensen’s had on the nascent trans underground. About the disintegration of her first marriage, and the joy of changing sex. About the ways she’d had to "mutilate" not her body but her history, her continuity, in order to pass unnoticed in mainstream society. So different and so similar to my own experience, a full five decades later.

Sometimes she’d describe absolutely horrific events with perfect sangfroid, laughing them off in what felt like an all-too-familiar trauma response. Once or twice, that mechanism would fail and she’d get solemn. Still, she was adamant that it was these "adventures" – and, more importantly, surmounting them – that made her innovations possible.

The most famous of those was a method of integrated circuit design known as Very Large Scale Integration (or VLSI), developed alongside the engineering professor Carver Mead, VLSI basically created the modern microchip industry, unleashing an abundance of digital devices that allowed me, decades later, to find her website and then to find others like me.

Lynn saw early on the power of the proto-internet – then known as ARPAnet – to spread knowledge laterally, circumventing old gatekeepers and traditions. She was, she recalled, "like some kind of wild den mother" to the smart young eccentrics she gathered to her cause, galvanising them towards a common goal.

I’ve had so little contact with ‘my own kind’ for all these years, and she was a role model.

That was Lynn’s theory of technological change, you see. Not a few "great men" driving history forward with the sweat of their brows, but networks of people in conversation with each other, learning to use newly-emerging tools to fulfil their own desires. Just point out the secret path, make it easier to walk, and soon it’ll become a railroad.

Which brings me back to trans folk and parenting. As a people, we have been systematically deprived of knowledge about ourselves. Many of us had to fight to even realise what we are, let alone advocate for our needs. We will never know how many of us died still living in the closet, or without even having a name for their feelings. All we know is how few survived to become ‘elders’.

Consequently, we often end up raising each other. I never would have guessed I was trans in the first place without examples. Nor would I ever have found the courage to act on it without my trans mentors. I’m here because of them, and today there are others who are here because of me.

This is the golden thread that connects trans people through the generations, frayed and twisted as it often is. It’s a key theme of so many artworks by trans women, from Torrey Peters’ hit novel Detransition, Baby through the fourth Matrix film to the beautiful indie video game Secret Little Haven. If you’ve ever seen queer folk praise someone as "mother!", that comes from the Ballroom culture that was built by mostly Black and Latino LGBT+ people in the late 20th century, as a family for those who had none.

Lynn’s work, and her website, made all of this much easier. She evidently felt it was important for her to be a mentor to younger trans people, and would often reach out directly with advice and support.

"I was a trans student who barely spoke English, posting my doodles on the internet, and she made me feel like my voice mattered," recalled Quebecois cartoonist Sophie Labelle in an email. "She was so generous with her time! She witnessed my growth as an artist and even when we disagreed on things, her support wouldn’t wither."

AC Quinlan, a trans writer in Wyoming, similarly told me about their correspondence with Lynn in 2015 and 2016.

"I’ve had so little contact with ‘my own kind’ for all these years, and she was a role model," Quinlan said. "I just started hormone replacement therapy last month, and I’d actually thought about sending Lynn an email shortly afterwards.”

Lynn offered me that encouragement too. After our interview we agreed to stay in touch, and I was genuinely looking forward to doing so. Last June she emailed me to say she’d enjoyed my mammoth Pride Month feature about trans people during the Covid-19 pandemic. "Congratulations on crafting that powerful synthesis," she wrote. "It reveals so many entangled threads for public reflection and discussion."

I’m ashamed to admit, however, that I wasn’t a great penpal. I kept meaning to send her articles I thought she’d enjoy, then forgetting to do it. Maybe you can see now why my feelings about Lynn’s death might echo the grief and guilt people sometimes feel after losing relatives that they’d meant to be in touch with more. We find our elders where we can.

Lynn’s passing, at the end of a long and happy life, doesn’t mean the thread is broken. It winds on still, through everyone that drew inspiration or strength from her and everyone they strengthened and inspired in turn. Goddess willing, one day we’ll make the kind of world I think she was working towards: a world where no one is orphaned anymore.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments