‘A stain you can’t wash off’: Legal hurdles make normal life impossible for former convicts

Tracy Jan meets the formerly incarcerated whose hope of getting operational licences will be a test of how much the system is willing to forgive

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.He had spent 17 of his 46 years behind bars, locked in a pattern of addiction and crime that led to 16 prison terms. Now, Meko Lincoln pushes a cart of cleaning supplies at the re-entry house to which he had been paroled in December, determined to provide for his grandchildren in a way he failed to do as a father.

“Keep on movin’, don’t stop,” Lincoln sings, grooving to the R&B group Soul II Soul on his headphones as he empties trash cans and scrubs toilets at Amos House. He passes a bulletin board plastered with hiring notices – a line cook, a warehouse worker, a landscaper, all good jobs for someone with a felony record, but not enough for him.

Lincoln, who is training to be a drug and alcohol counsellor, wants those lost years to count for something more.

“I lived it,” he says. “I understand it. My past is not a liability. It’s an asset. I can help another person save their life.”

Yet because regulations in Rhode Island and most other states exclude people with criminal backgrounds from many jobs, Lincoln’s record, which includes sentences for robbery and assault, may well be held against him.

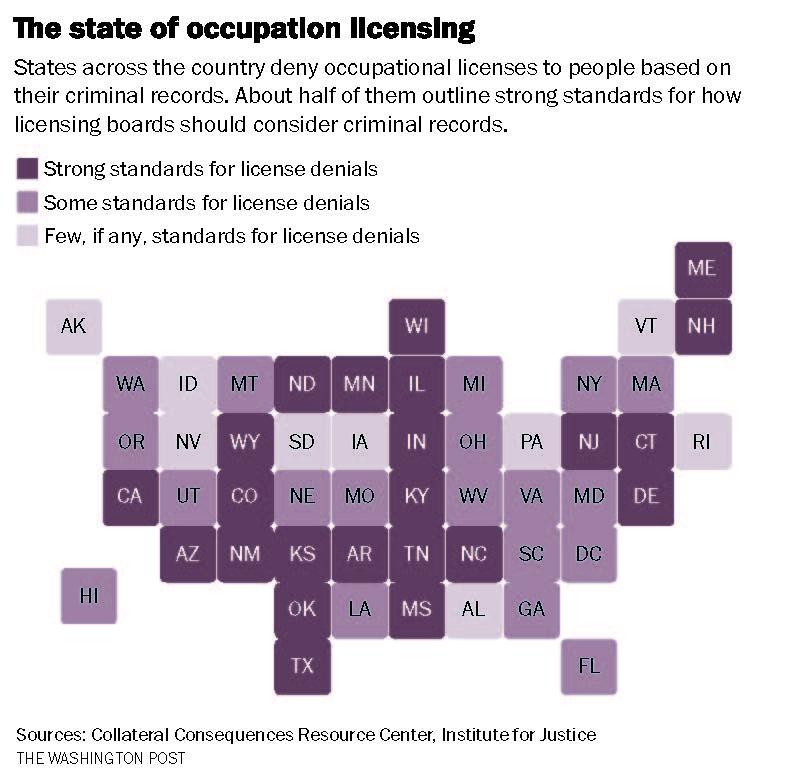

Across the country, more than 10,000 regulations restrict people with criminal records from obtaining occupational licences, according to a database developed by the American Bar Association. The restrictions are defended as a way to protect the public. But Lincoln and others point out that the rules are often arbitrary and ambiguous.

Licensing boards in Rhode Island can withhold licences for crimes committed decades ago, by citing a requirement that people display “good moral character” without taking into account individual circumstances or efforts towards rehabilitation.

I lived it. I understand it. My past is not a liability. It’s an asset. I can help another person save their life

Such restrictions make it challenging for the formerly incarcerated to enter or move up in fast-growing industries such as healthcare, human services and some mechanical trades, according to civil liberties lawyers and economists. These include the very jobs they’ve trained for in prison or in re-entry programmes like Lincoln’s. And without jobs, many of those released could end up back in jail, experts say.

Lincoln’s hope of getting licensed as a chemical dependency clinician will be a test of how much the system is willing to forgive. His 16 prison terms resulted from charges including narcotics possession, resisting arrest, obtaining money under false pretences, malicious destruction of property and assaulting police officers as well as repeated parole violations for returning to drugs, according to the Rhode Island Department of Corrections.

Lincoln says his crimes were committed while he was intoxicated or high, or trying to obtain heroin and crack cocaine. He would buy drugs, dilute them and resell them to other people with addictions, actions that resulted in robbery charges. He sold fake drugs to undercover police and hit a drug dealer’s car with a crowbar.

Licensing restrictions are among the many obstacles to establishing a stable economic footing after prison. Incarceration carries a stigma, and many employers are wary of hiring people who have spent time in prison.

But states with the strictest licensing barriers tend to have higher rates of recidivism, according to research by Stephen Slivinski, an economist at the Centre for the Study of Economic Liberty at Arizona State University.

“In many states, a criminal record is a stain that you can’t wash off,” Slivinski says. “There is no amount of studying that can take away this mark in your past if a licensing board wants to use it against you.”

Even Rhode Island, a state on the forefront of sentencing reform, has some of the nation’s most restrictive licensing regulations, according to separate analyses by the liberal National Employment Law Project and the libertarian Institute for Justice.

For Lincoln, obtaining a licence could mean the difference between the $25,000-a-year (£21,000) job as a “peer recovery coach” he’s being trained for at his re-entry programme at Amos House and the $50,000 he could earn a year as a chemical dependency clinician – a licensed drug and alcohol counsellor who can treat people with addictions, not just mentor them.

“Licensing legitimises us as somebody,” he says. “It’s recognition.”

And there is a need for more black counsellors like Lincoln as the share of minorities dying of opioid overdose rises in Rhode Island and across the country.

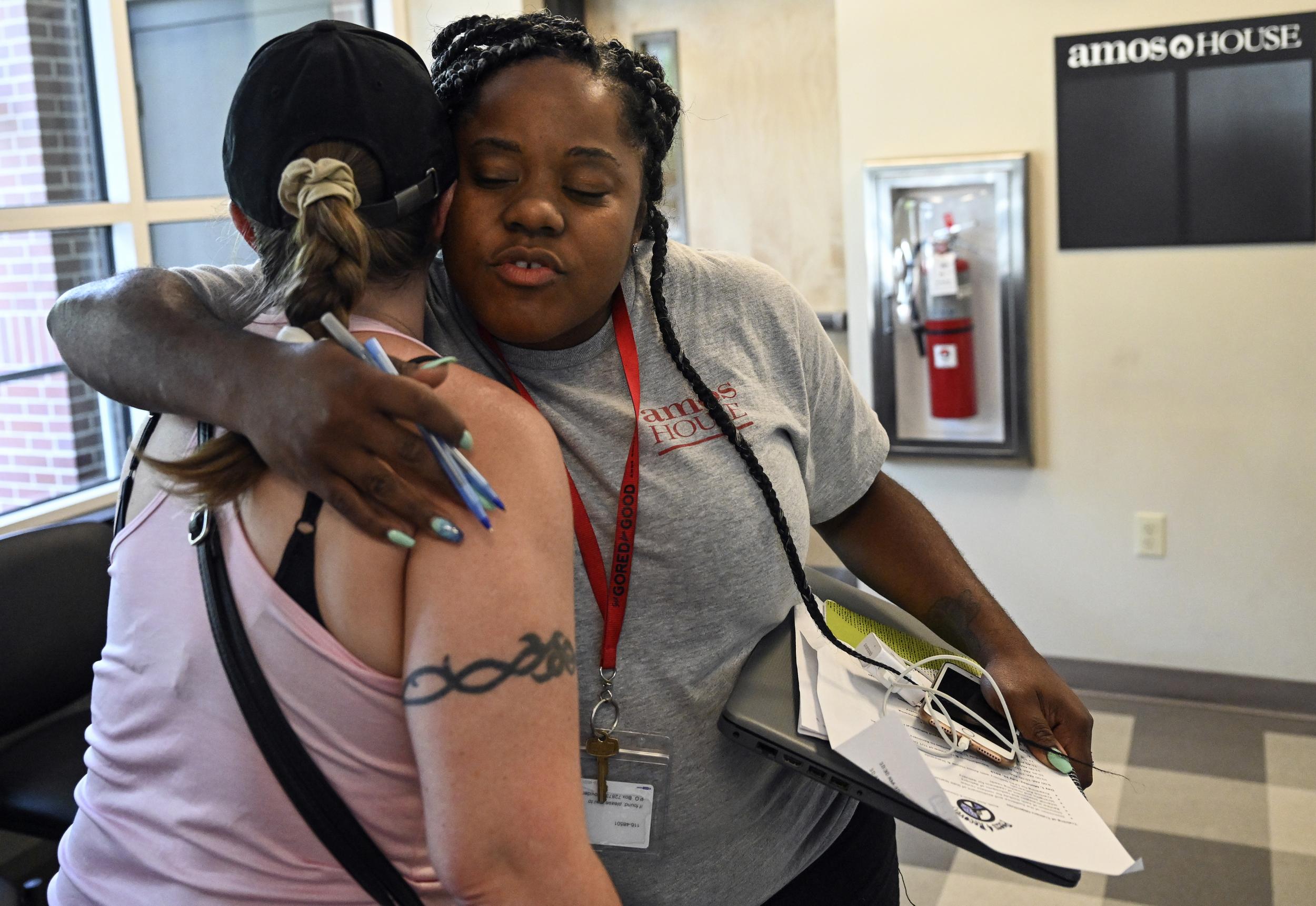

“He has the life experience that would allow somebody else to say, ‘Well, if Meko can do it, I can possibly do it, too,’ “ says Amos House chief executive Eileen Hayes, who offered Lincoln the chance to train as a recovery coach after witnessing his progress

In May, as instructors passed out certificates during a ceremony on the last day of his recovery coaching class, Lincoln tried to focus on all that he had accomplished in the six months since his release from prison.

He had stayed clean through a 90-day rehab programme. Moved from the bottom bunk in the rooming house he shared with 19 other guys into his own basement apartment nearby. Got a job, making $11 an hour as a custodian.

Soon he would start a paid internship as the weekend night manager of the men’s residency at Amos House, where he had lived until February.

Amid his classmates’ cheers and applause, anxiety crept in: what if this is as good as it gets?

In many states, a criminal record is a stain that you can’t wash off. There is no amount of studying that can take away this mark in your past if a licensing board wants to use it against you

Now Lincoln ambles through the crowded Amos House cafeteria dispensing hugs, elbow bumps and compliments in Spanish and English. Bald, clean shaven except for a short goatee, with 18in biceps bulging beneath his shirt sleeves, Lincoln is unrecognisable from the skeleton he used to be in the depths of his addiction.

“I see something nice! You blinging!” he shouts to a woman with a new set of teeth.

He wraps his arms around a man in his sixties who is recently back from detox and snags a piece of his cinnamon roll. A guy in line for chilli and Spanish rice who knew Lincoln from prison calls out to him: “I just got out. I got no ID. No transportation. No nothing.”

The people seeking food, job training, counselling and shelter here are a constant reminder to Lincoln of how quickly sobriety can unravel. This was his second pass through Amos House, a social service agency whose clientele include the homeless, people seeking help with addiction and the formerly incarcerated.

The first time, Lincoln relapsed soon after completing the 90-day programme, availing himself of the drugs being sold just blocks away. He returned to prison for three years for heroin possession, stealing drugs and beating up a drug dealer.

“Instead of facing life on its terms, I kind of folded like a lawn chair,” he says.

Rhode Island Superior Court justice Kristin Rodgers told Lincoln during his 2016 sentencing hearing that he could not blame his relapse on the pressures of sobriety or his difficult childhood.

“The problem with you, Mr. Lincoln, is that when you go to the dark side, you go big,” Rodgers said, according to the court transcript. “And you have victims that are out there. There are robberies, there’s drug dealing. These are not victimless crimes, sir.”

Lincoln responded that his crimes were driven by the disease of addiction, committed largely against others in similar situations.

“I never take anything from anybody that ain’t taken something from me,” he told the judge. “And when I’m on drugs, it’s the people that’s using drugs.”

Lincoln grew up in a south Providence neighbourhood surrounded by poverty, drugs and violence. His father was in prison for murder and struggled with his own addiction. His mother raised four boys largely on her own.

He says he began drinking and smoking marijuana with older teens at age 12 – then started using crack cocaine and selling it, picking up his first possession charge at 14.

He says he was talented enough at football that he was approached by college scouts, but that dream evaporated in a string of arrests and stints in juvenile detention. He dropped out of high school his junior year.

He was homeless, high and just 19 when his first daughter, Janelle Hazard, was born. At 21, Lincoln served his first term in prison – 14 months for robbing a drunk man of a bottle of liquor in 1994.

Hazard ended up in foster care, begrudgingly getting to know her father in weekly prison visits during a 10-year sentence – Lincoln’s longest – for a 2002 robbery conviction. While serving that sentence, he learned he had a second daughter: the two remain estranged.

Lincoln says the 2002 conviction resulted from a false accusation by a Providence narcotics detective. Public records show the detective pleaded guilty to charges related to drug dealing in 2010 as part of a larger cocaine operation.

Over his years in prison, an older inmate taught him to read and write. He read the Quran and embraced Islam, a religion he says taught him how to forgive – himself and others.

During his last stint, Hazard brought her own two boys for Saturday visits. Her sons developed a bond with their grandfather, throwing mini footballs in the visiting room decorated with Disney characters. Her third child, a girl, was born while Lincoln was imprisoned.

Lincoln would mail his grandchildren CD recordings of his voice reading them books. He wants to be a model for them, in the way he was not for their mother.

“When she was being raised and needed me, I wasn’t there,” Lincoln says. “I wanted to present them with proof that they could one day become something they want to be.”

He participated in behavioural therapy and entered a chemical dependency program, which inspired him to consider counselling as a career.

In his last six months of incarceration, he recalls propping a folded paper name tag on a table in the day room. As guys around him played cards and chess, Lincoln played therapist. “I was trying a shoe on to see how it would fit,” he says, “acting as if I had an office.”

Other inmates made fun of him. But some sat down to talk, venting about their cellmates or corrections officers.

In October, two months before he was paroled, Lincoln wrote a letter on a piece of notebook paper to the coordinator of the men’s programme at Amos House. “If given the opportunity to be released back there, I will not repeat the cycle,” he wrote.

When he got out, Lincoln had been sober for three years – the longest he’d been clean in decades.

Hazard, now 27, picked him up, driving him to his grandsons’ school. He jumped out of the SUV in his blue prison-issued sweatsuit, yelling, “Surprise!” Then Hazard and the boys, now eighr and seven, dropped him off at Amos House, hopeful it would be the last time.

When she was being raised and needed me, I wasn’t there. I wanted to present them with proof that they could one day become something they want to be

Lincoln committed to daily 12-step meetings, working through childhood feelings of abandonment during group therapy, and coping with feeling insecure, powerless and useless. Through it all, his urine tests remained clean.

In July, Lincoln embarked on accumulating the 500 internship hours he needs to be certified as a peer recovery coach – his first step towards his goal of becoming a licensed drug and alcohol counsellor – while holding onto his afternoon cleaning shift.

As Lincoln heads to an afternoon prayer service at his mosque, an unshaven man with matted hair stopps him on the steps of Amos House.

“I’ve missed you, man,” slurs Lincoln’s childhood friend, his face drawn and pupils constricted, as he pulls Lincoln in for an embrace. “You know how sometimes you feel like you’re walking around and you’ve got no soul?”

Lincoln asks if he wants to get clean. His friend does not answer. Instead, he asks: “You don’t got no five dollars? No bud on you?” Lincoln shakes his head no. “I love you.”

The entirety of Rhode Island’s state prison population is confined to one square mile in Cranston, where 2,640 inmates are divided among six facilities surrounded by barbed wire and armed guards.

Rhode Island reduced its prison population by 23 per cent between 2008 and 2016, in part by giving inmates time off their sentences for participating in academic classes, rehabilitative programmes, paid work or job training.

Jorge Henriquez shaved more than one year off his five-year sentence for dealing cocaine by taking classes and working in the prison car body shop.

The 32-year-old father of two is halfway through a course in heating and air conditioning, a fast-growing field, and is excited about the prospects of a lucrative – and legal – career.

“When you have a record, there’s not a lot of good-paying jobs out there,” says Henriquez, who is scheduled for parole in February.

Rhode Island does not officially bar people with criminal histories from being licensed in HVAC, but under state law, licences in HVAC and other mechanical trades can be revoked or suspended for felony convictions.

Bill Okerholm, the HVAC instructor, says that the union of plumbers, pipe fitters and refrigeration technicians accepts people with records as apprentices on a case-by-case basis. But of the 250 men he’s trained at the prison in the past five years, Okerholm can’t recall anyone who has been licensed after their release.

“Guys like Jorge deserve a second chance,” says Okerholm, noting Henriquez’s enthusiasm and attention in the course. “There’s a great need in these trade jobs for someone like him.”

With a quarter of the US workforce in a licensed occupation, compared with just 5 per cent in the 1950s, more than two dozen states have begun to loosen licensing restrictions – but Rhode Island is lagging behind.

While opponents say current licensing regulations are ambiguous and inconsistent, supporters of the licensing regime say undoing the restrictions would usurp the authority of state boards and create additional burdens for agencies. More important, supporters say that the regulations are aimed at protecting public health and safety, and that it would be irresponsible to let people with criminal records, especially those involving violent offences, enter certain professions.

An attempt at change – with a bill that would have limited licensing denials to people whose crimes directly relate to an occupation – died in the Rhode Island General Assembly in June when the house introduced an amendment excluding those convicted of a violent crime. The broad definition, which included robbery, larceny and burglary, would have excluded people like Lincoln.

“Some state agencies expressed concerns that were valid and can’t be disregarded,” Rhode Island house speaker Nicholas Mattiello, a Democrat, says. He adds that the house would revisit the issue when a new legislative session begins in January.

¼

of the US workforce is in a licensed occupation

Criminal justice policy analysts say the licensing barriers discourage people with records from applying in the first place because they are routinely told their convictions make them ineligible.

Few states collect this type of data, but in Texas, 15 per cent of prospective applicants to the state Department of Licensing and Regulation in the past four years were deemed ineligible through a criminal history evaluation letter – an optional preliminary review of their convictions, the agency says.

In many of those cases, determinations were based on decades-old convictions or crimes irrelevant to the licences being sought, according to letters obtained by the Texas Criminal Justice Coalition. The department says those who wish to be reevaluated may now do so under new criteria established by lawmakers that only crimes directly related to the job can be grounds for denial.

About a dozen states have enacted more modest reforms, according to the Institute for Justice. California’s 2018 bill requires convictions be “substantially related” to an occupation for licences to be denied. Florida, New York and Iowa recently eased licensing restrictions for a limited number of occupations. Meanwhile, bills introduced this year in South Carolina, Louisiana, Missouri and other states failed to advance.

Partaja Spann-Taylor, one of Lincoln’s classmates in his recovery coaching course, is a reminder to Lincoln of the barriers to developing a career post-incarceration. The 34-year-old – whose criminal record is far slighter than his – pursued jobs in health care and social services when she got out of prison a decade ago – only to be met by rejection after rejection because of her criminal background.

Spann-Taylor was charged with delivering cocaine and reckless driving in 2006 when her then-boyfriend made a drug delivery. She was released on bail after two weeks in jail and got five years of probation and a suspended sentence.

In 2008, when she was four months pregnant, she was incarcerated for 30 days after her friends got into a fight at a nightclub. She was charged with assault, even though she said she did not participate, because her presence violated the terms of her probation.

After her release, Spann-Taylor tried to enrol in a free training programme to become a certified nursing assistant.

She was rejected. Her felony record disqualified her, she was told – shutting her out not only from future licensing but from training as well.

“A lot of people would say, ‘Well, stick with the retail and the food service industries. They’re the most forgiving in terms of your background,’ “ Spann-Taylor says. “But I needed to make a living for me and my daughter.”

She considered a career in physical therapy. But that too has licensing barriers. She says an admissions officer at New England Institute of Technology told her that she would need to pass a criminal-background check for clinical placement or employment.

So Spann-Taylor waitressed at a steak house while getting her associate degree in human services and then a bachelor’s degree in social work.

After graduating from college in 2013, she got a job as a court advocate for domestic violence victims, but the offer was rescinded before she could even start when her felony conviction showed up in a background check. A second job offer, a teaching position at a prison, was also rescinded because of her criminal record.

It took five more years of waitressing before Amos House offered her a job getting homeless, drug-addicted women off the streets of Providence.

In May, Spann-Taylor, now a married mother of two, enrolled part time in a master’s programme to become a clinical social worker – even though her felony record could end up disqualifying her from licensing.

People lose hope when the door keeps closing in your face. I got frustrated thinking I was just going to be a waitress for the rest of my life. I’ll keep trying to bust through these doors until they open

Under Rhode Island law, licensed clinical social workers must be free of felony convictions – unless the professional board determines those previous convictions aren’t a risk to public safety. The state health department says it has no record of anyone with a felony conviction applying for a licence in social work or chemical dependency counselling in the past five years.

Spann-Taylor knows she will struggle to persuade the licensing board to overlook her record. Even if she obtains her licence, some major health insurers will not contract with providers with felony backgrounds. At times, she wonders whether the $40,000 she’s accumulated in student loan debt will be worth it. Still, she feels she has little choice.

“People lose hope when the door keeps closing in your face,” she says. “I got frustrated thinking I was just going to be a waitress for the rest of my life. I’ll keep trying to bust through these doors until they open.”

Lincoln knows that with his lengthier prison sentences, he faces even higher career hurdles. So he focuses on what he can control – learning as much as he can about counselling, piecing together as many internship hours as possible, staying clean and making things right with his family.

His “training ground” – as Lincoln calls it – was the red three-storey house where he spent the first three months after his release, learning how to abide by rules and routine outside prison walls and how to feel the emotions he buried while he was incarcerated or high.

“Once you put the drugs down, all those feelings you were trying to numb come rushing back – you sold yourself short, neglected your family, the guilt,” Lincoln says. “I didn’t know how to be a dad. I didn’t even know how to be a human. I just existed. I breathed. I ate.”

Freedom felt confusing at first. He relished showering alone, eating with a fork rather than a spork, opening the windows and seeing squirrels and birds. Yet he was anxious being in public spaces like restaurants, buses and grocery stores, fearing judgement from strangers, anxious about his future and the pressure to get himself together.

And there were moments of regret and shame. It hurt to hear his eight-year-old grandson use “crackhead” as a playground insult. It hurt when the boy tried to dig in his pockets for a dollar and Lincoln pulled out a wallet devoid of bills because payday wasn’t until the next day. It hurt to admit he was secretly relieved when his grandchildren came down with pinkeye, because he didn’t have the $70 to take them to Chuck E Cheese as they’d planned.

Now he talks about his feelings. His daughter says they’ve never been closer. But it’s still early. Her mind won’t ease until he’s stayed out of prison for at least a year.

“He’s never pushed this hard,” Hazard says. “I’m afraid he’s going to give up – because of the past. I don’t want my kids to go through what I went through. I don’t want them to experience the heartbreak that I felt.”

At his kitchen table, Lincoln pores over a chart of Freud, Jung, Piaget and Erickson he’d drawn as a study aid for an introduction-to-counselling course. He’s 15 credits shy of his associate degree.

In August, his fiancee, Andrea Heath, moved into his one-bedroom apartment from the sober house where she had been living. They met at Amos House, shortly after his release from prison. He was borrowing a suit for a job interview. She was drawn to the bounce in his step.

“My first thought was wow, this guy is going places,” says Heath, 33, who makes $10.75 an hour manufacturing defibrillators. “I’ve never met someone who’s been so motivated and makes me want so much more in life.” They’ve talked about having children in a year or two.

Every day, Lincoln drives the mile from their apartment to Amos House, travelling the same roads he used on, passing the corner where he was last arrested. Heroin addicts shoot up on porches, and bundles of dope are sold in the open. Lincoln keeps a bag of naloxone in his glove compartment – and another in the trunk – in case someone overdoses.

In one week alone, Lincoln learned of two deaths: a childhood friend and a neighbour’s boyfriend who had just got out of prison.

“It’s a stark reminder that I have these opportunities,” he says, “but at any given moment, this disease can attack anybody.”

Just before midnight, Lincoln returns to the “men’s house” – this time as the overnight manager. The eight-hour shift would count towards his training as a counsellor.

He arrives with a plastic grocery bag containing his prayer rug and a library book: The New Jim Crow, Michelle Alexander’s account of the permanent second-class status of black men who have been incarcerated. “The real punishments begin when we are released from prison,” Lincoln says.

He hopes to pick up more shifts at the house, helping men like himself restart their lives and, in doing so, helping himself stay on the right path. “It’s a good reminder that I don’t want to be here again,” he says.

By 2am the house is still, the television off. Lincoln climbs two flights of stairs to conduct his hourly head counts, peeking into each of the four bedrooms with no locks. The only sound is snoring. Upon returning to the brightly lit office by the front door, Lincoln opens the window and savours the cool, fresh air.

Just before 4am, he unfurls his green prayer rug and points it east. He removes his red Nike high-tops, loosens his belt and rolls up the legs of his jeans. Then he kneels, trying not to think about the mouse he’d seen scurrying across the room earlier in the night.

In an hour, the men will start to wake, groggily rolling into the office with cigarettes tucked behind their ears and seeking permission to step out for a smoke.

Lincoln will open the top right drawer of the desk and distribute the cellphones that had been confiscated for the night so that no one would be tempted to text their dealer. He will unlock the closet where baskets of medication are kept, logging how many doses of Suboxone were swallowed by clients to help manage their addictions.

And he will say goodbye to a lanky guy with long hair who was asked to leave because he could not stay clean, just as Lincoln failed to stay clean three years ago.

But for the next three minutes, Lincoln recites the dawn prayer, touching his forehead to the rug – grateful, in this moment, that he’d made it to the other side.

© Washington Post

Subscribe to Independent Premium to bookmark this article

Want to bookmark your favourite articles and stories to read or reference later? Start your Independent Premium subscription today.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments