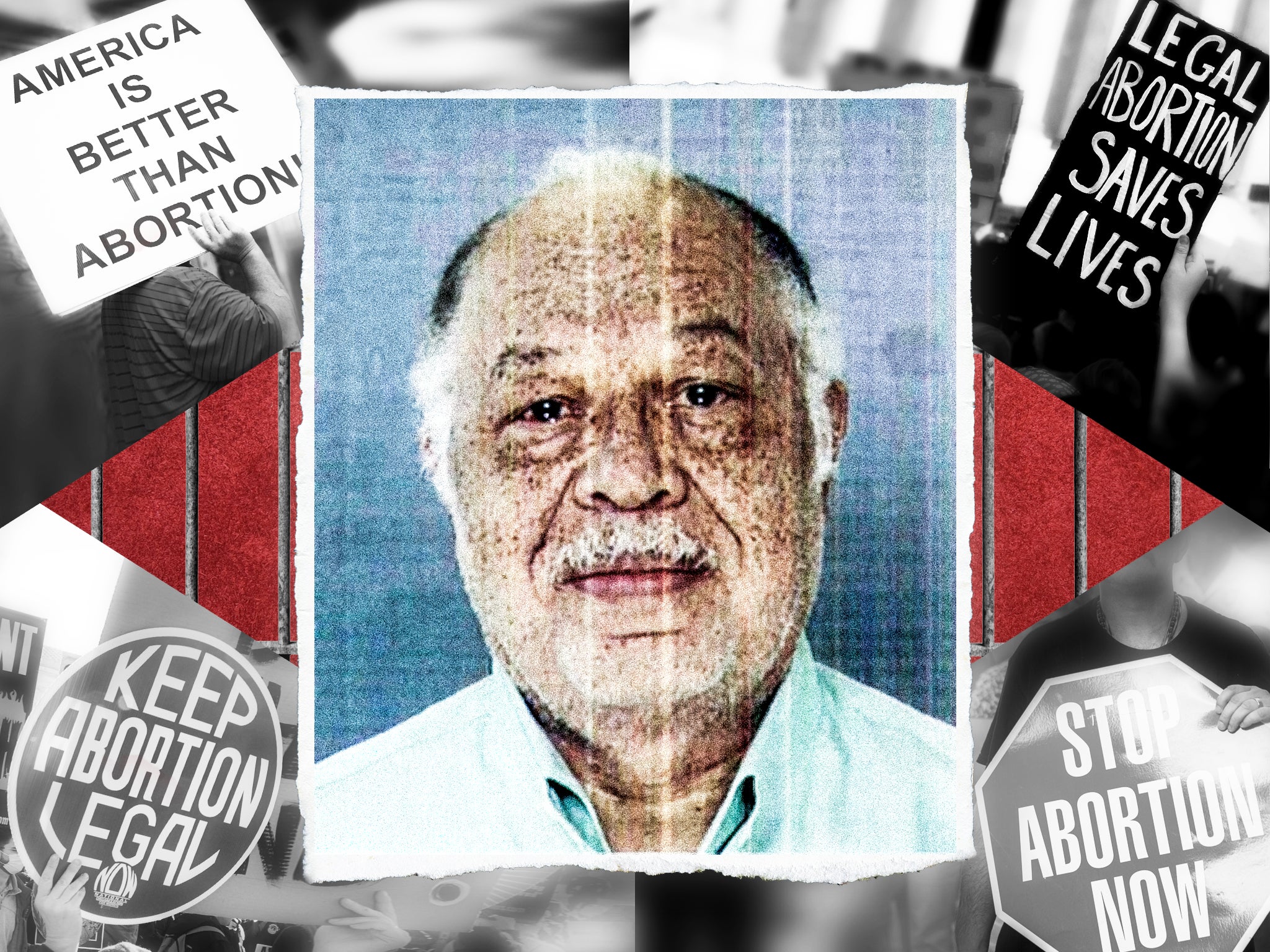

Kermit Gosnell butchered women and babies for decades. The anti-abortion movement weaponised his horrors

Behind the doors of Kermit Gosnell’s ‘house of horrors’ clinic were countless vulnerable women with nowhere else to turn. But when his crimes were finally exposed, their stories became lost in the anti-abortion movement. Rachel Sharp reports

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Robyn Reid was just 15 years old when a doctor fought her down onto a table, ripped off her clothes, tied her arms and legs with restraints and forced her to undergo an abortion against her will.

It was 31 January 1996, and the teenager had spent the last three months hiding her pregnancy from her grandparents as she prepared for a new life raising her baby.

When they found out, Robyn’s grandmother had driven her from their home in New Jersey to a notorious west Philadelphia clinic nicknamed “Club Abortion”.

“I was determined to keep the baby,” Robyn, now 40, tells The Independent.

“My plan was to go to the doctor and refuse to have the abortion as I thought ‘no one can make me.’ My 15-year-old brain thought there wasn’t even a chance that would happen to me.

“Inside the clinic, I remember being in the room and the doctor walked in and said: ‘Why aren’t you undressed?’ When I told him ‘I’m not having an abortion’, he shouted: ‘I don’t have time for this s***.’

“He then walked out of the room and came back in with my grandmother… Then he started pulling my clothes off.”

Robyn, a small 90-pound teenager, fought with all her strength.

“I was fighting him as he pulled my clothes off and held me down,” she says.

“He was tying my arms down with straps and, then every time he tied my legs down, I managed to pull my arms free. It went on and on like that – it was a physical fight.”

In the end, she could fight no more.

“He overpowered me to the point that I could no longer move. I remember looking up at the light and saying to myself: ‘Just don’t go to sleep’. Then he gave me a needle,” she says.

“The next thing I knew, I woke up 12 hours later and I was back home in New Jersey and was no longer pregnant.”

Sobbing, she adds: “I’ll never forget that day.”

It would be years before Robyn would learn that she was one of countless women given illegal or dangerous abortions at the hands of a man who some would describe as a “butcher of women”, others as “one of America’s biggest serial killers”.

More than 14 years passed before the truth of Kermit Gosnell’s “house of horrors” was finally exposed to the world.

‘House of horrors’

On 18 February 2010, the FBI carried out a raid on the Women’s Medical Society on Lancaster Avenue, west Philadelphia, as part of an investigation into the illegal sale of prescription drugs.

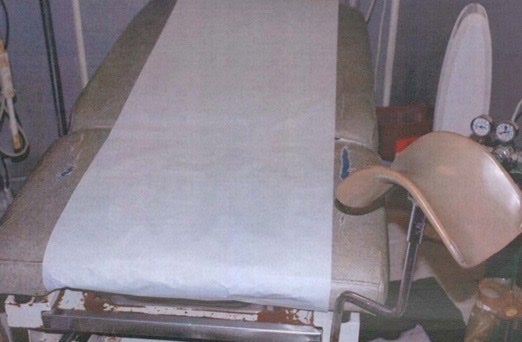

On entering the clinic, the federal agents had no idea of the extent of the horrors they would find inside.

Semi-conscious and heavily-sedated women lay on dirty recliners and bloodstained blankets moaning in pain.

A mix of blood and cat feces covered the floors – the latter from the flea-ridden animals roaming the space where women were undergoing medical procedures.

Jars up jars of severed baby feet were stacked inside the refrigerators.

By the end of the search, authorities had found 47 aborted fetuses and infants stored at the facility – including one late-term infant frozen inside a water bottle.

The dangerous conditions and unspeakable scenes were only the start.

In the four decades prior, Gosnell had been running his “house of horrors” clinic in a deprived neighbourhood in west Philadelphia.

It was a place where poor, migrant, minority ethnic, and vulnerable women could pay cash to have late-term abortions well after Pennsylvania’s legal limit of 24 weeks.

A place for women who – due to poverty, lack of healthcare and other factors driven by inequality – ultimately had nowhere else to turn.

Or for women and young girls like Robyn who had their right to choose taken away from them with no questions asked.

In many cases, it wasn’t even an abortion clinic - but rather an infanticide clinic where babies were delivered at near-full term and then murdered.

While Robyn’s forced abortion was within the legal timeframe in the state of Pennsylvania, countless other women underwent the procedure at Gosnell’s clinic in the seventh, eighth and even ninth month of pregnancy.

These babies were delivered alive at full term, breathing and moving.

It was then that Gosnell – and sometimes colleagues who had zero medical training – carried out what he called “ensuring fetal demise” by a procedure he named “snipping”.

This “procedure” involved sticking a pair of scissors into the back of the newborn baby’s neck and cutting the spinal cord, severing the brain from the body.

It was murder.

As the 2011 grand jury report investigating Gosnell’s actions states: “This case is about a doctor who killed babies and endangered women. What we mean is that he regularly and illegally delivered live, viable babies in the third trimester of pregnancy – and then murdered these newborns by severing their spinal cords with scissors.

“The medical practice by which he carried out this business was a filthy fraud in which he overdosed his patients with dangerous drugs, spread venereal disease among them with infected instruments, perforated their wombs and bowels – and, on at least two occasions, caused their deaths.”

And for years and years, Gosnell got away with it.

‘Butcher of women’

It’s impossible to know exactly how many babies or women died at Gosnell’s hands.

Baby Boy A – as he was referred to in the grand jury report and at trial – was around six pounds when Gosnell induced the labour of his 17-year-old mother at 30 weeks of pregnancy and he was born breathing and moving.

Gosnell “snipped” the baby’s spine and dumped him in a shoe box, joking that the baby was so big that he could “walk me to the bus stop”.

Baby Boy B was at least in week 28 of pregnancy when he was aborted and his body placed in a one-gallon spring-water bottle and frozen.

Baby C lived and breathed for about 20 minutes before one of Gosnell’s workers “snipped” their neck.

Baby D was born in a toilet and was moving when they was killed.

At least two women are also known to have died.

The first woman, Semika Shaw, died of sepsis in 2002 after Gosnell botched the abortion procedure and perforated her uterus. She was 22.

The second fatality was Karnamaya Mongar, a 41-year-old refugee from Bhutan who had recently arrived in the US from a resettlement camp and gone to the clinic for an abortion in 2009.

She was given an unrecorded amount of the dangerous – but cheap – sedative Demarol.

When she stopped breathing, there was no working defibrillator to try to get her heart working again.

Instead of immediately calling 911 and performing life-saving measures on Mongar, clinic staff tried to cover up what was happening by staging the scene to appear as though she had been undergoing a safe, legal procedure.

By the time she got proper medical attention, it was too late. Her cause of death was found to be an overdose of sedatives.

On 15 May 2013 – three years after the FBI raid – Gosnell was finally convicted over some of the deaths and horrifying goings-on at his clinic.

He was found guilty of three counts of first-degree murder in the deaths of Babies A, C and D, involuntary manslaughter in Mongar’s death, 24 counts of performing an abortion beyond the 24-week limit and numerous other charges.

He is currently serving three life sentences behind bars in State Correctional Institution Huntingdon.

Eight other clinic workers including Gosnell’s wife were also convicted on various charges – some of them of murder.

Battle over reproductive rights

There’s no doubt that the case of Kermit Gosnell is a real life horror story.

But, it’s also a key chapter in the wider story of America’s battle over reproductive rights.

For anti-abortion activists, groups and politicians, the case became one of their strongest weapons to push for abortion bans, shorter term limits and tighter restrictions on abortion clinics.

Following his arrest, the name Gosnell instantly became fodder for the right to argue that tougher laws and fewer abortion rights was what the country needed.

When he introduced a resolution calling for Congress to investigate abortion clinics in 2013, Republican Senator Mike Lee called Gosnell’s case a “wake-up call” for the nation.

Texas Governor Rick Perry meanwhile described Gosnell’s case as “the awakening of a sleeping giant in this country to protect babies”.

And in many cases, the rhetoric appeared to work.

By the time Gosnell was convicted in May 2013, stricter abortion laws had already been rolled out in several states, with Arkansas banning most abortions after 12 weeks and North Dakota after six.

Tougher laws were also making their ways through the legislatures of other states including North Carolina, Texas, Wisconsin and Ohio.

What Gosnell’s case had done was give the anti-abortion movement “credibility” in its efforts to “demonise” abortion doctors, clinics and – ultimately – abortion rights altogether, says Mary Ziegler, UC Davis Martin Luther King Jr Professor of Law and an expert in the politics of reproduction and healthcare in the US.

“His case lent credibility to the anti-abortion arguments of the era,” she tells The Independent.

“It wasn’t the case that what he did changed how anti-abortion groups were arguing… Before this case, they were already trying to demonise anti-abortion doctors. But until then, it had been easier to dismiss what they were saying as a political strategy.”

For years, the anti-abortion movement had framed abortion as murder and pro-choice advocates as people who supported “killing babies”, despite late-term abortions already being illegal.

In Gosnell, the anti-abortion movement for the first time had a real-life figure that they could point to as an example to support this argument.

“Kermit Gosnell made it easy for anti-abortion groups to push this narrative,” says Professor Ziegler.

“After Kermit Gosnell was discovered, these anti-abortion groups said ‘this is representative of what all abortion doctors are like and of what abortion in general is like’.

“Which of course wasn’t true but it made it easier for them to demonise abortion providers more than in the past as they now had a prominent example. This was no longer hypothetical.

“So it was framed that, in order to prevent Kermit Gosnell from happening again there was a need to shut down abortion and abortion clinics. The idea that the next Kermit Gosnell could be out there lent credibility to this argument.”

She adds: “The movement needed villains to tell the story and in modern history he was the most famous.”

The clinic itself became and continues to be used as a physical reminder of the horrors of what went on inside.

Indeed in 2019, anti-abortion groups sought to buy the clinic on Lancaster Avenue and turn it into a crisis pregnancy centre, reported local outlet WHYY.

The efforts appear to have stalled as four years later the looming building is still owned by Gosnell himself – with the 82-year-old racking up tax bills on the property from prison.

There’s also the regular memorials left by anti-abortion advocates at the Laurel Hill Cemetery, which became the burial site of the 47 fetus and infant remains found in the clinic which became known as the “Gosnell babies”.

The forgotten stories

Meanwhile, what was entirely lost from the story was the women – and why they had ended up at the inhumane clinic on Lancaster Avenue in the first place.

The clinic largely served a poor neighbourhood of west Philadelphia with most patients being low-income, migrant or ethnic minority women.

They didn’t have access to quality healthcare. Paying cash for what was essentially a backstreet abortion was the only option available to them in their current predicaments.

“These were people who were shut out of adequate healthcare and were not able to get what they needed from society,” says Professor Ziegler.

“There are gaps in the healthcare system such that some people were so desperate to turn to that – but very quickly that dimension of the Kermit Gosnell story vanished.

“It became just that abortion providers are butchers and they’re in it for the money – and this being a story about inequality in America just dropped off… the women were lost from the debate.”

Robyn perhaps proves this when she tells The Independent that of the multiple times she has been asked to share her story about what happened to her at Gosnell’s clinic, until now no one has ever asked her where she personally stands in the abortion debate.

The experience at Gosnell’s “house of horrors” has left her with complex views.

“I think in one way I didn’t have a right to choose – my choice was taken away from me that day. So I don’t want to take that choice away from other women,” she says.

“But going through that also made me want to stick with more conservative values as in a world where abortion doesn’t exist this wouldn’t have happened.”

She adds: “I am more in support of anti-abortion laws than not… but I also believe in a women’s right to choose… I don’t think they are opposites, you can believe in the right to choose but also in the right to life.”

West Philadelphia’s worst kept secret

As well as the voices of women like Robyn, something else was also lost from the story of Gosnell’s “house of horrors”: the irony that what he did was already illegal.

The reality is that abortion bans would not have stopped Gosnell because he was already knowingly breaking the law.

Gosnell knew what he was doing was wrong, but didn’t care.

And, disturbingly, it appears that authorities also knew at least in part what was going on as well.

Over the years, several complaints had been made about Gosnell and the clinic’s reputation as an “abortion mill” had become the worst kept secret in the city – and yet Gosnell continued to work unchecked for decades.

When Gosnell’s clinic – and what went on inside – became national news in 2010, one of the biggest questions asked was, how he had gotten away with it?

The findings of the grand jury report revealed a disturbing lack of enforcement and willingness to turn a blind eye by multiple government agencies.

Pennsylvania’s Department of Health, which was responsible for auditing the clinic, had information which should have led to its shutdown but it failed to act, the grand jury found.

In 1993, the agency had stopped carrying out inspections at abortion clinics – a move the grand jury report blamed on “political reasons” when the pro-choice Republican Governor Tom Ridge took office.

Yet, even though the inspections stopped, the alarm was still raised through several complaints sent to the department from other medical centres, from lawyers representing women, and even from an insurance company representing the 22-year-old victim who died on his operating table.

The grand jury report outlines one principle reason for why the issues were ignored time and again.

“Bureaucratic inertia is not exactly news. We understand that. But we think this was something more,” it reads.

“We think the reason no one acted is because the women in question were poor and of color, because the victims were infants without identities, and because the subject was the political football of abortion.”

Historically, Black and Hispanic women face greater barriers to access to all aspects of reproductive healthcare.

Hispanic and Black women face a disproportionately higher risk of unintended pregnancy, according to research in Contraception and Reproductive Medicine journal.

Black women make up 40 per cent of abortion patients – the largest share of all ethnic groups – while also having a maternal mortality rate 2.6 times higher than white women, CDC data shows.

Several other systemic barriers also often exist, such as lack of heath insurance, lower income to afford quality healthcare – not to mention longstanding discrimination in the healthcare industry towards Black women.

The role that race and inequality played is something that’s not lost on Robyn, who is Black but grew up in a white, suburban middle-class neighbourhood.

“One of the things it’s put in perspective for me is how, being a Black person, it seems like our abortions are not as important,” she says.

“I am Black but grew up in a white neighbourhood and there were always protests outside the abortion clinics there.

“There was no one protesting outside Gosnell’s clinic. That makes me a little angry like ‘where were you guys when the doctor violated me?’

“It’s a bit like no one cares if you go and have an abortion in the slums but not here in our nice white neighbourhood.”

Now she is older and Gosnell’s crimes have come to light, Robyn says she believes it was Gosnell’s reputation which caused her grandmother to take her there.

“I lived in New Jersey where there were multiple abortion clinics. I think he was purposely chosen because he had a bad reputation that if you went there any hour of the day, no matter how far along or in what circumstances he would get the job done,” she says.

The grand jury report revealed that – while the clinic was depraved all round – women of colour were subjected to worse treatment than white women at Gosnell’s clinic.

While white women were taken to the one clean room in the building, women of colour would be taken to filthy rooms, according to testimony from a former employee.

“I do wonder if I was a white person might there have been more concern?” questions Robyn.

And yet – as this month marks ten years on from Gosnell’s conviction – the biggest impact of the case is still its use as a tool to try to crack down on abortion access.

Kermit Gosnells in a post-Roe world

While it’s impossible to know what weight Gosnell’s crimes had on the overturning of Roe v Wade, Professor Ziegler says the same strategy of “demonising” abortion doctors and clinics is still very much alive and well today.

Pointing to North Carolina’s latest abortion law – a 12-week ban on almost all procedures in the state – she says “you can see a lot of the same elements now” in the language and argument for the ban.

“It’s still a leading strategy of the anti-abortion movement to seek restrictions on the clinics… we still see it happening today but in a different context,” she says.

The long-term impact of the case in the wider abortion debate can be seen in other ways too.

For one, Gosnell’s case took the debate around reproductive rights out of the doctor’s clinic and placed it firmly in the criminal courts. Here was a doctor on trial for the procedures he had performed on women.

Now, in a post-Roe world, doctors are faced with the threat of criminal charges as they struggle to navigate new laws – many of which have created uncertainty about the legality of procedures even where women have miscarriages or ectopic pregnancies.

That said, the demon doctor narrative is becoming harder for the anti-abortion movement to use to justify tighter regulations and outright bans, says Professor Ziegler.

In the months since Roe v Wade was overturned, Republican-led states have passed increasingly restrictive abortion bans and pushed back access to abortion for millions of Americans.

With abortion severely restricted or banned in some states, it’s hard to argue for even more restrictions.

Also, when around half of all abortions in the US are now medication abortions – telehealth – the “demon doctor” narrative also doesn’t fit the mold.

“The demon doctor idea doesn’t work as well today as people have more active roles and more autonomy in their abortions,” explains Professor Ziegler.

“And also there are now a lot of places where abortion is a crime so doctors aren’t performing them.

“So what’s happening is that women are having miscarriages or need emergency treatment and if a doctor tries to deliver care they risk going to prison – those are the stories we’re hearing now so the Kermit Gosnell story doesn’t fit.”

Rather than abortion bans and restrictions preventing a Kermit Gosnell case from ever happening again, the fear is that it will actually lead to a world where more Kermit Gosnells come to exist.

With some lawmakers banning almost all abortions in their states – and some also banning out-of-state travel for abortions – underground, backstreet abortions may become the reality in lieu of legal, safe options.

And women may have no other option other than turning to the next Kermit Gosnell.

“Even when abortion was legal, you had butchers like Kermit Gosnell,” says Professor Ziegler.

“Now there’s the fear that people will be forced into unsafe situations in places where abortion is a crime. It’s not just abortions it’s also ectopic pregnancies and miscarriages and people will be more likely to return to people like Kermit Gosnell if they can’t access healthcare.”

Professor Ziegler points out that while healthcare and abortion providers and groups have worked to ensure women in states with bans aren’t cut off from treatment – through medication access or travel funds – the now confusing and ever-changing laws mean people will struggle to navigate legality and know what they can and cannot do within the law.

“Wherever abortion is criminalised or where people don’t have easy access to abortion, there’s the risk of more dangerous abortions happening,” she says.

“Where you don’t have easy access to get out of state for an abortion or when you’re unsure what the law is, I would expect to see more dangerous abortions happening.

“Women left resorting to doing dangerous things on their own – and to turning to more people like Kermit Gosnell.”