This man turned down a plea deal because he says he’s innocent. He’s spent 33 years in prison

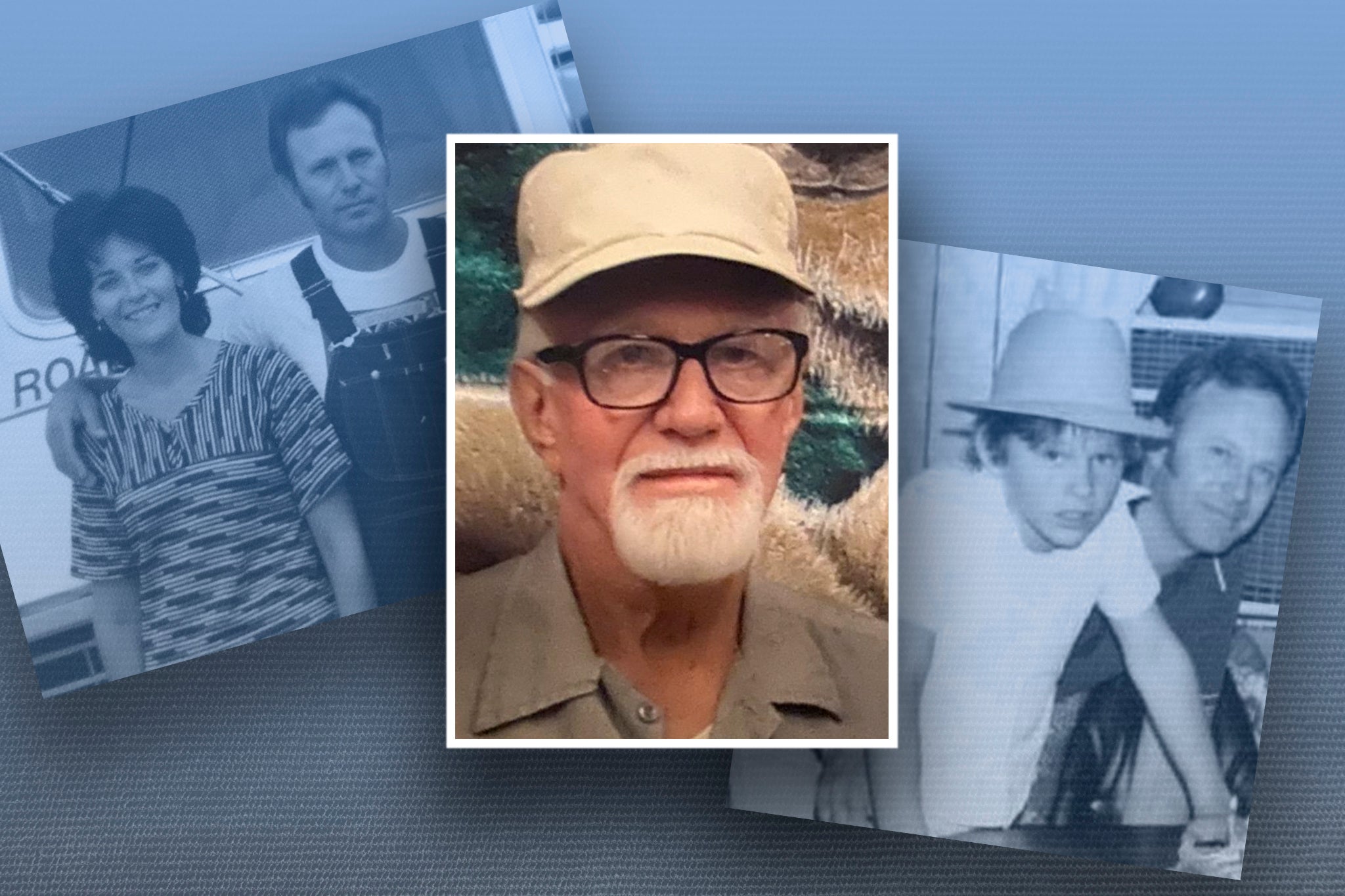

It’s been 33 years since Ken Middleton, now 79, was convicted of murdering his wife. Due to a procedural technicality, Mr Middleton has sat in prison for nearly two decades trying to appeal his case again. Andrea Blanco reports

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.In 2004, Ken Middleton made a decision that has cost him nearly two decades of freedom. After being convicted of killing his wife, a crime he maintains he did not commit, prosecutors offered him a deal: He had already spent 14 years in prison for her murder but if he took a plea deal, he would be able to walk free.

Mr Middleton refused, determined to clear his name with a new trial and have his entire conviction overturned.

Nineteen years later he’s still waiting for that chance.

“Most innocent people would have taken that plea just to get out of prison, so I don’t fault anyone for taking it who is innocent,” his son Cliff Middleton told The Independent., “But one thing I can tell you beyond any doubt whatsoever… Every guilty person is going to take that plea.”

Mr Middleton insists his wife, Kathy Middleton, died by accident as she fumbled with a gun.

For the last two decades, Mr Middleton, now 79, has been waiting for a trial that was promised to him — and never delivered.

Months after prosecutors’ plea offer, Judge Edith Louise Messina granted Mr Middleton a new trial after an evidentiary hearing in which Mr Middleton’s new counsel presented evidence that it would have been nearly impossible for him to shoot at the trajectory that his wife was shot.

Prosecutors waited until Judge Messina ruled in favour of Mr Middleton’s request to then file a motion alleging that the judge did not have the jurisdiction to decide on the matter.

“We put on all this evidence and we win,” Cliff told The Independent about the evidence suggesting his father is innocent of murdering his stepmother. “And then [the prosecution] comes back and say, ‘You did it in the wrong courtroom,’ and threw it all out, never addressing the merits that the judge ruled on in a 38-page order tossing out his conviction.”

Ever since, Mr Middleton’s case has been tangled in the technicalities of a system that gave him a glimpse of hope in his fight for freedom and then took it away.

“Imagine after the Kansas City Chiefs won the Super Bowl, and they said, ‘Hold on a minute. We should have played it in California, not in Las Vegas’ and took away their Super Bowl,” said Cliff. “That’s the equivalent of what happened to us.”

Last year, Mr Middleton’s attorney filed legal documents arguing that Jackson County Prosecutor Jean Peters Baker has failed to file an order to vacate Mr Middleton’s conviction under a 2021 law that allows the state to do so when evidence emerges that a convicted person “may be innocent or may have been erroneously convicted.”

It is the same law that allowed Ms Baker to vacate Kevin Strickland’s conviction. Mr Strickland was exonerated 43 years into a 50-year prison sentence for a triple homicide he did not commit.

But the prosecutor has shown no interest in correcting the system’s wrongs in Mr Middleton’s case. Ms Baker’s office has not yet responded to The Independent’s request for comment.

“It’s cruel and it’s wrong,” Cliff said. “After turning down his freedom, after [securing] a new trial. He has sat in prison, proven a wrongfully convicted man.”

And those years of injustice hurt.

“When I see people get out, they seem forgiving that justice finally worked,” Cliff said. “They’re a different breed than I am because I’ll never forget what the state of Missouri has done to my father and my family.”

A promise 19 years due

In 2004, family members and friends of Ken Middleton sat in the gallery for his evidentiary hearing.

There had been momentum building around the hearing, and Mr Middleton’s family spent a large sum to make sure this time he had a strong defence. The hearing was akin to a “mini-trial,” Cliff said, and by the end of it, Mr Middleton’s supporters believed they had reached a turning point.

The Middleton family flew in forensic experts from out of state, and they had a new team of lawyers. They had their hopes set on a favourable ruling and it seemed like freedom was lurking around the corner.

One of the arguments introduced by Mr Middleton’s defence was that the attorney who represented him during the trial had not presented a case at all. After he was arrested, Mr Middleton’s assets were frozen and he had to rely on the kindness of a close family friend who paid for his trial lawyer, Robert Duncan.

Duncan was handling three death penalty cases along with Mr Middleton’s and was found to have left out facts critical to Mr Middleton’s case.

He was later found to be ineffective and disbarred. During Mr Middleton’s trial, he did not raise a defence, didn’t put experts on the stand and didn’t enter any evidence.

There were also personal relationships with the legal team that may have impacted the trial. In a 1996 affidavit seen by The Independent, Duncan said that he later found out the father of the lead prosecutor in Mr Middleton’s case was representing his wife’s sisters in a civil lawsuit against Mr Middleton.

The law firm of the prosecutor’s father also represented the police department that led the investigation into Kathy Middleton’s death. Neither the prosecution nor the police department disclosed the conflict of interest.

An expert who testified at the 2004 two-day hearing cast doubt on the police department’s theory of the shooting.

“The expert testified that it was just impossible for my dad to have shot her because she was shot from eight inches away, and the trajectory of the bullet was at a steep angle. He couldn’t have shot her and gotten out of the way [to avoid] any blood spatter on him,” Cliff said.

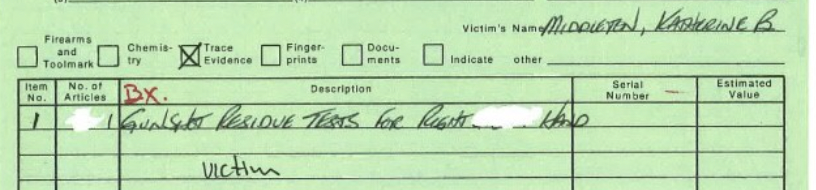

Kathy Middleton was shot from the left. Although her right hand tested negative for gun residue, the results of the test taken from her left hand never made it to court.

The left-hand test was also never sent by police to the laboratory. In excerpts of Judge Messina’s ruling reviewed by The Independent, she wrote that jurors saw a document filled out by crime scene investigators that stated the right hand had been tested and when held to light, it could be seen that the “left hand” part had been removed with white-out.

“To this day, nobody has ever explained where the left hand went,” Cliff said.

‘I’d plead guilty to killing Abraham Lincoln’

At the hearing, former Governor Missouri Joseph Teasdale also said Mr Middleton’s was “the worst case of constitutional violations he had witnessed,” according to a transcript seen by The Independent.

Judge Messina wouldn’t rule for another 11 months, but just two weeks after the evidentiary hearing concluded, the Jackson County Prosecutor’s Office came back to Mr Middleton with an Alford plea offer — a type of deal that allows a defendant who maintains their innocence to accept a plea bargain.

Mr Middleton did not take it.

When Judge Messina’s ruling came, the state appealed the decision on jurisdictional grounds. An appeal court later ruled in favour of the prosecution and revoked the judge’s decision.

“They offered him his freedom if he pleaded guilty, but because he wanted the trial judge to exonerate him … What does [the prosecution] do? They turn around and appeal the decision and hide behind a procedural background,” Cliff says.

“I’ll never forget. One of the [prison] guards … told my dad that he would have pled guilty to killing Abraham Lincoln and John F Kennedy if they would let him out of that place.”

Mr Middleton’s current attorney, Kent Gipson, joined his case five years after the prosecution’s appeal. He has exhausted nearly every legal remedy available to Mr Middleton since and now hopes that a new judge can give them a new chance to argue their case at a status hearing scheduled for March.

“This case has probably got more twists and turns than just about anything I’ve dealt with,” Mr Gipson told The Independent. “I’ve been up and down through the courts, I don’t know how many times in the last 14 years and nothing’s ever worked. The way I look at it, and that’s probably the only way I haven’t gone insane or dropped dead is, all I can do is do the best I can.”

‘Son crusades for father’s freedom’

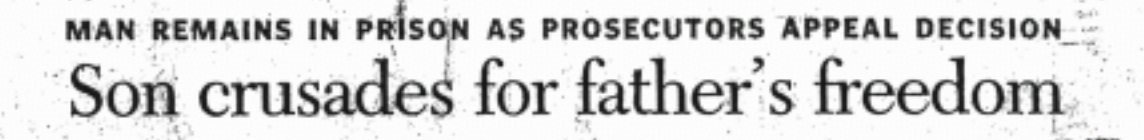

Following Judge Messina’s ruling, the Kansas City Star ran an article featuring Mr Middleton’s story titled “Son crusades for father’s freedom.”

“So for now he remains in prison,” the last line of the piece read.

Inspired by the headline, Cliff bought a billboard in downtown Kansas City with the same legend.

But “for now” turned into months, then years, and Mr Middleton has since remained in prison for two more decades. He speaks to his son nearly every day, but the missed family gatherings, birthday celebrations, and time with his grandchildren — and now great-grandchildren — have weighed heavily on the family’s morale.

“[My children] have never seen him outside of a prison visiting room with a white T-shirt on,” Cliff said. “They’ve never seen my dad in street clothes as a normal human being like I did.”

Still fighting a legal system that has proved flawed, unreliable and even negligent, Cliff now knows by heart the date of every legal defeat. He has spent the last three decades studying any case that bears similarities to his dad’s, and learning a myriad of legal terms he never dreamed of becoming familiar with when he first found out his father had been arrested in 1990.

“This has been my life’s work,” Cliff said. “I thought my dad was coming home. I thought it was over. And we had that yanked away from us.”