John Adams was right, July 2nd is really America's Independence Day

It was on July 2, 1776, that the Second Continental Congress meeting in Philadelphia voted to approve a motion for independence

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Everybody (presumably) knows that July 4th is America’s Independence Day. But John Adams, who had a lot to do with the American colonies’ break from Great Britain, had other ideas. He thought July 2nd was the date that would be celebrated “as the great anniversary festival.” Why?

Here’s a post I published three years ago, with a few changes.

On July 3, 1776, John Adams, a leader of the American Revolution who later became the second president of the United States, wrote a letter to his wife Abigail with this prediction:

The Second Day of July 1776, will be the most memorable Epocha, in the History of America. I am apt to believe that it will be celebrated, by succeeding Generations, as the great anniversary Festival. It ought to be commemorated, as the Day of Deliverance by solemn Acts of Devotion to God Almighty. It ought to be solemnized with Pomp and Parade, with Shews, Games, Sports, Guns, Bells, Bonfires and Illuminations from one End of this Continent to the other from this Time forward forever more.

July 2nd? Why did he not write her another letter, on July 4th or 5th, and say his prediction was premature?

Because it was on July 2, 1776, that the Second Continental Congress meeting in Philadelphia voted to approve a motion for independence put forth by Richard Henry Lee of Virginia. Twelve of the 13 colonies approved it, while New York abstained, as its representatives did not have permission to vote for it at that time. What became known as the Lee Resolution officially separated the thirteen American colonies from Great Britain. Later that day the Pennsylvania Evening Post published this:

“This day the Continental Congress declared the United Colonies Free and Independent States.”

So why do we celebrate July 4th as Independence Day? It’s because the actual Declaration of Independence was adopted by the Continental Congress on that day in 1776. Thomas Jefferson, the principal author, had been working on it during the summer, going through different drafts, seeking advice from Adams and Benjamin Franklin and having others at the Congress work on it as well.

The city of Philadelphia, where the Declaration was signed, waited until July 8 to celebrate, with a parade and the firing of guns. The Continental Army under the leadership of George Washington didn’t learn about it until July 9.

As for the British government in London, well, it didn’t know that the United States had declared independence until Aug. 30.

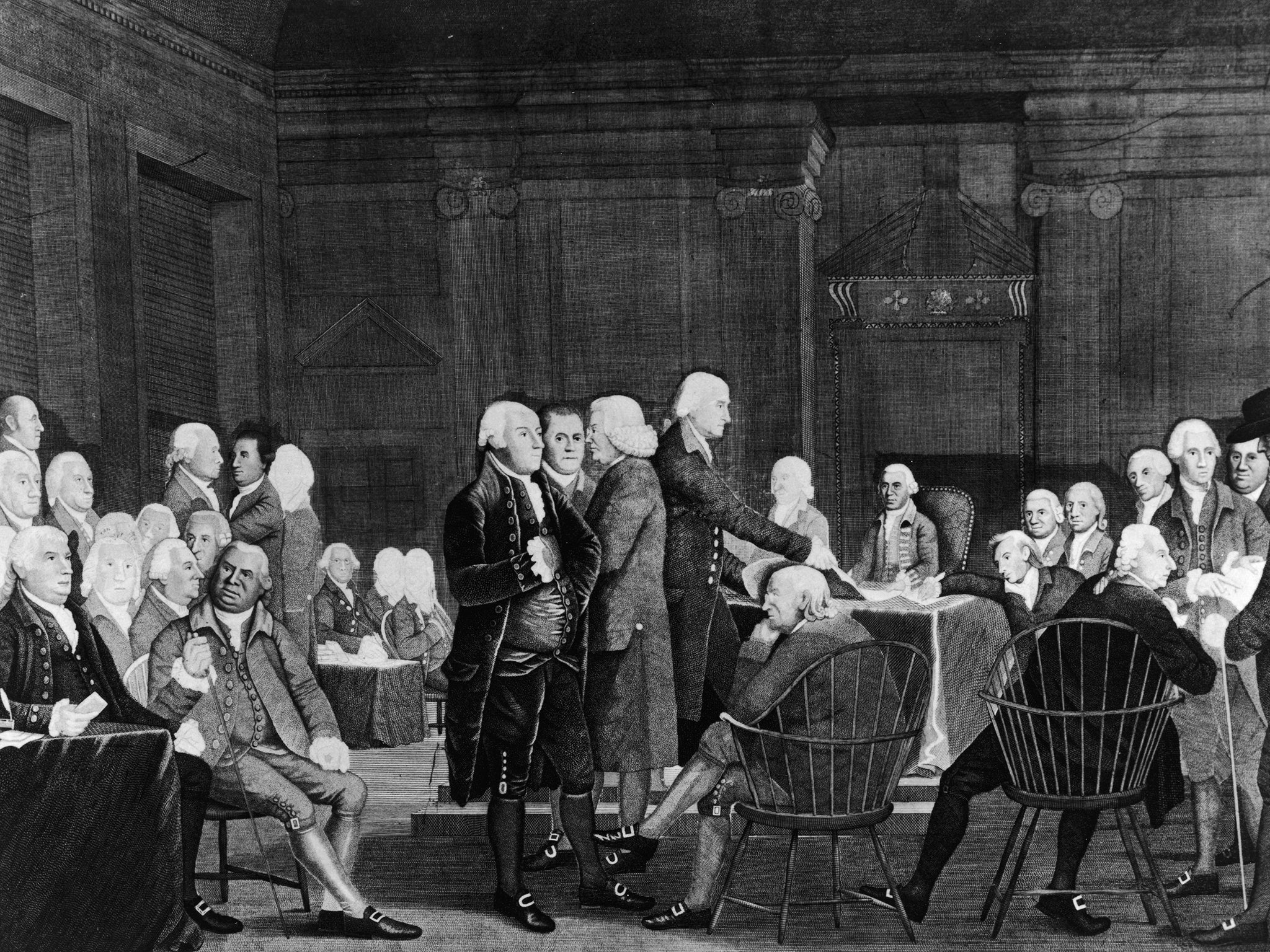

Scholars don’t think the document was signed by any of the delegates of the Continental Congress on July 4th. The huge canvas painting by John Trumbull hanging in the grand Rotunda of the U.S. Capitol depicting the signing of the Declaration is, it turns out, a work of imagination. In his biography of John Adams, historian David McCullough wrote: “No such scene, with all the delegates present, ever occurred at Philadelphia.”

It is now believed that most of the delegates signed it on Aug. 2. That’s when the assistant to the secretary of Congress, Timothy Matlack, produced a clean copy.

John Hancock, who was the president of the Continental Congress, signed first, right in the middle of the area for signatures. The last delegate to sign, according to the National Archives, is believed to be Thomas McKean of Delaware, some time in 1777.

In a twist of history, Adams died on July 4, 1826, the same day as Thomas Jefferson, the 50th anniversary of the adoption of the Declaration of Independence.

Copyright: Washington Post

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments