He had always believed in the justice system – then he spent 22 years in prison for a murder he didn’t commit

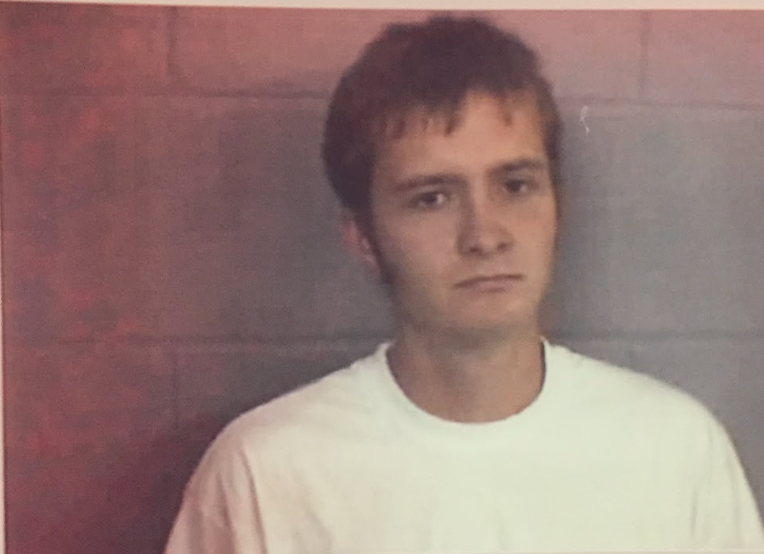

Joey Watkins was wrongly convicted of murder in 2001. Twenty-two years later, he tells Andrea Blanco how the criminal justice system failed him – and how he is now on a path to rebuilding his life

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.The hug Joey Watkins gave his parents on 3 January 2023 had been more than two decades in the making.

His parents had visited him in prison throughout his 22 years behind bars, fervently convinced that he had been wrongly convicted of murder, but this embrace was sweeter for the knowledge that he was coming home with them.

That day, the 43-year-old walked out of the prison where he had spent more than half of his life after a jury overturned his conviction for the 2000 murder of 21-year-old Isaac Dawkins in Rome, Georgia.

His emergence from the prison marked only a partial freedom, as he was still on bail, strapped with an ankle monitor and facing the possibility that prosecutors would choose to pursue a second trial against him.

“The hardest thing during that time period was being away from my family and nobody listening to me,” Mr Watkins tells The Independent of his time behind bars.

“Everybody always told me, ‘You were convicted by a jury. You had to do this. You did something. You knew something.’ Nobody would listen to me.”

Ten months on from his release, his fears of being sent back to prison have finally gone.

Following excruciating years of legal defeats and the discovery of exonerating evidence in a joint investigation by the Georgia Innocence Project (GIP) and the podcast Undisclosed, the Floyd County District Attorney’s Office officially dropped the case against Mr Watkins in late September.

The investigation had uncovered evidence of juror and official misconduct as well as the concealment of pivotal information by authorities during the initial criminal investigation, according to Christina Cribbs, an attorney with the GIP.

But Mr Watkins’ newfound freedom still carries a bitter aftertaste, as he reckons with the reality that many of the people who believed in his innocence are no longer here to celebrate with him. Without entitlement to financial compensation for his wrongful conviction under Georgia law, he has taken over his family car business as he looks to move on with a life that was irrevocably split when he was just 20 years old.

“Now that my charges have been dropped, I can start the healing process,” says Mr Watkins.

“You work so long and so hard to be released and then when it finally happens, it’s kind of like running a marathon. When you finish, you’re relieved and you feel a sense of accomplishment, but at the same time, it’s like, ‘What’s next? I fought for so long. That’s been my objective and my goal, and I’m finally here and it’s finally done but also, what’s next?’”

The GIP has set up a GoFundMe to help support Mr Watkins while he settles into his new life. The non-profit is actively working towards a statutory compensation bill in the state, Ms Cribbs said, but working with legislators to pass a bill is a lengthy and complicated process.

“For people who have been wrongfully convicted, like Joey, there should be a simple, clear objective way for them to try to get some semblance of repayment,” Ms Cribbs tells The Independent.

“And we have to also recognise that Joey could be given $50m and that is still never going to make up for the 22 years that he lost incarcerated. But the least we can do as a society is to recognise that he does deserve some compensation.”

‘I believed in the justice system’

When he was first approached by detectives following Dawkins’ death, the then-20-year-old Mr Watkins could have never fathomed that he would wind up spending the next 22 years of his life in prison wrongly convicted of his murder. Instead, he thought any suspicions police had about him would be cleared up after they had questioned him, he says.

And, that was the case for an entire year after Dawkins’ murder.

It was the night of 11 January 2000 when Dawkins’ car was found on the side of a highway in Rome, Floyd County.

Inside, Dawkins was found shot in the head. He was transported to a local hospital where he later died.

Mr Watkins, who knew the victim and had once argued with him over a girl they had both dated, was initially questioned and cleared as a suspect. But a year after the murder, Sergeant Stanley Sutton, a new investigator from the Floyd County Police Department, took over the case and honed in on the animosity between Mr Watkins and the victim.

“I was young, I was a kid ... I didn’t think it was real,” Mr Watkins says. “I believed in the justice system, my eyes were not open to what they’re to open now because I believed in the system. Everybody kept saying, ‘If you didn’t do anything then you have nothing to worry about.’”

After a $10,000 reward was offered, a witness came forward to authorities to claim that they had seen a small blue car tailing Dawkin’s car on the night of his murder.

Mr Watkins – who drove past the crime scene that night after law enforcement responded to the scene at around 7.20pm – had been driving his white pickup to go visit his girlfriend, who lived 30 miles away from Rome in Cedartown.

Investigators raised the theory that Mr Watkins had switched cars during the short time frame to throw off law enforcement before committing the crime. They claimed that he switched cars back again before driving to his girlfriend’s home.

“An independent witness saw what was sort of a road rage [incident], where there was a small blue car and the victim’s truck playing cat and mouse on the road, just driving really crazy and slamming on brakes,” Ms Cribbs says.

“The state ... had to start making up ideas. It’s nothing more than wild speculation from the state trying to place Joey in a car that he was not in.”

Witnesses also claimed to have seen Mr Watkins leaving his home in his white truck and then near his girlfriend’s place nearly 45 minutes later in the same vehicle. For the state’s theory to work, Mr Watkins would have had to previously know that Dawkins would be on that road, switch cars and drive at 55 miles per hour while talking to his girlfriend on the phone – all of this within 45 minutes, the amount of time that it would have taken for him to drive straight from his home to his girlfriend’s, according to the GIP.

Phone records also placed Mr Watkins miles from the crime scene.

“Something was not right. [Sgt Sutton] was kind of pressuring teenagers and didn’t exactly do the right thing, I guess you would say. I knew then I was in trouble,” Mr Watkins says of the early investigation.

According to the Undisclosed podcast, Sgt Sutton began pressuring supposed informants who had spent time in prison with a friend of Mr Watkins, Mark Free.

Sgt Sutton, who died earlier this year, failed to corroborate the informants’ stories and accused Mr Watkins and Mr Free of a conspiracy to kill Dawkins.

Despite all the evidence against his involvement, Mr Watkins was charged and went to trial in 2001. He was convicted on charges of murder, possession of a firearm and stalking and sentenced to spend the rest of his life in prison for Dawkins’ murder.

Meanwhile, Mr Free was acquitted of the charges one year later.

Where did justice fail?

Initially, Mr Watkins believed it would just be a matter of time before the system corrected itself. But days turned into months, months turned into years and eventually, he says, his chances of having his innocence reinstated before a court of law and winning back his freedom seemed less and less likely.

“In the beginning, I still had hope, but as the years went by, I realised that I could be in prison for life,” Mr Watkins tells The Independent. “Probably eight to 10 years into my sentence, it was really hard not to lose hope. I just kind of stuck with my faith and kept praying.”

His frustration was exacerbated when he was transferred to a prison far away from his family and he found himself further removed from his main source of support – the people who believed he did not pull the trigger on Dawkins that fateful night.

Despite the distance, his parents kept supporting him and went on to spend their life savings on the revolving door of attorneys who took and abandoned Mr Watkins’ case throughout the first 15 years of his sentence.

“I’ve had several attorneys that were great and I had some that were not so great, but they tried to an extent,” Mr Watkins says. “If you have someone that’s not as compassionate as the GIP or someone that’s not getting paid to help you, I guess you could say it’s a job to them. My family ... they spent everything they ever worked for in their life trying to get me home.”

In prison, Mr Watkins says he met people who asked him to drop the act and admit he was guilty, as well as people who believed him. Still, his attempts to be heard by the system that could actually make a difference were fruitless.

“Think of it like this – you’re fighting a giant, you know you’re caught on the web and you’re still trying to fight the giant. The power that the justice system has, they can sometimes choose to exercise that power, so to speak, and not listen to anybody.”

The case took a turn in 2016, after the GIP started working with Mr Watkins and the popular podcast Undisclosed covered his case and the chain of mistakes that landed him in prison.

According to Ms Cribbs, the GIP’s legal team was able to raise three main issues in a 2017 Habeas Corpus petition thanks to the joint investigation between the podcast and the non-profit organisation.

“The specific evidence in this case that was withheld related to a dog that was found on or near the grave of the victim, in this case, and the dog had been shot,” Ms Cribbs says. “The prosecution really made a big issue about that and tried to say, ‘What kind of horrible person would kill a dog and put it near someone’s grave?’ and really tried to make Joey out to be a monster when he wasn’t involved in either one of those things.”

An autopsy determined that the bullet recovered from the dog’s corpse did not match the calibre of the bullet that killed Dawkins – suggesting a different weapon was used to kill the animal – but that information was never presented to the jury or handed to Mr Watkins’ defence. Ms Cribbs said that the state also allowed a witness from the Georgia Bureau of Investigation to give testimony that the dog was not examined.

“Claire Gilbert, the executive director GIP was finally, after years and years of trying, able to uncover that evidence only by chance,” Ms Cribbs said. “The medical examiner who did this autopsy happened to have his own personal records, still literally in his closet. He remembered it very clearly because he had only done dog autopsies a couple of times in his entire career and he gave this new case number that Claire was then able to use to start requesting these documents.”

The legal team also successfully argued that one of the jurors who convicted Mr Watkins had conducted her own test of the prosecution’s switching cars theory. The juror said she had done the test, subsequently admitting to going against specific instructions given by the court to refrain from doing so, during an interview with former Undisclosed host and attorney Susan Simpson.

“This jury was actually told, ‘Do not go out and drive around and try to figure these things out.’ But the juror did her own driving test and she did it wrong,” Ms Cribbs added.

“It led her to come to the conclusion that, Joey actually could have been there at the time. This particular juror, who had doubts about Joey’s guilt from listening to the trial evidence, did this test wrong and came to the wrong conclusion.”

Life after a wrongful conviction

Mr Watkins says that the evidence to exonerate him was always there.

“If you’re from the outside looking in, it’s kind of like a cardboard house. It looks dirty, but if you push just a little bit, it crumbles,” Mr Watkins says.

“There’s still a little bit of fear in me but I’m just grateful and I thank God everybody finally opened their eyes and looked at it.”

After he was released from prison in January, Mr Watkins, now 43, wasn’t completely certain that his freedom would be permanent. He claims that the district attorney’s office had continued to try to build a new case against him until recently.

“Before they dropped charges, I was getting a little nervous because, even though I know this is 2023 and not 2000 or 2001, it’s still scary,” he says. “I have a lot more support now, a lot more people know the truth but you still never know what can happen and the way the state did me with all the fabrication in the beginning.”

When reached by The Independent, Floyd County District Attorney Leigh Patterson declined to comment on the case, why his office decided to drop the charges, and whether the reports of prosecutorial misconduct are now under review.

Mr Watkins’ path to freedom was filled with obstacles and challenges that he is grateful he has now overcome.

But he is now left to process everything he went through these past 22 years.

“The people you lose when you’re incarcerated that long, people that stood by your side and that fought for you,” an emotional Mr Watkins tells The Independent.

“My grandmother and my grandfather, my uncle, people that were there for me who have passed during the time I was incarcerated. Coming home and not having them is another part of the whole process. I’m just now getting to a place where I can deal with that.”

As well as losing loved ones, Mr Watkins came home to a struggling business that he is now trying to save.

He is also trying to help his parents with the many medical problems they are currently facing. Shortly after his release, Mr Watkins’ father underwent surgery and the family is now dealing with the piling medical expenses and the financial aftermath of the years spent in legal counsel before the Georgia Innocence Project came into the picture.

“I’m just trying to make a way. I’m 43 now. I maybe got 10 to 15 years left to work, so If I’m compensated, I’m grateful,” Mr Watkins tells The Independent.

“But I can’t put all my eggs in one basket so I’ve got to move forward because if I’m not compensated, then I don’t have a lot of time to create something for me for when I’m older.”

And while he is moving forward with his life, Mr Watkins says he also hopes Dawkins’ family can find closure and justice so that they can move forward with theirs too.

“It’s not fair to anyone. They deserve peace, they deserve the truth,” he says of Dawkins’ family.

“And I’m sorry for all these years that I became their object of hate. I didn’t do this.”

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments