Jimmy Carter: His father was a white supremacist, but a black farmhand gave him faith and purpose

A complex and confounding man, says his biographer, Jonathan Alter, who looks at the extraordinary life and achievements of this misunderstood American president and the people who shaped him

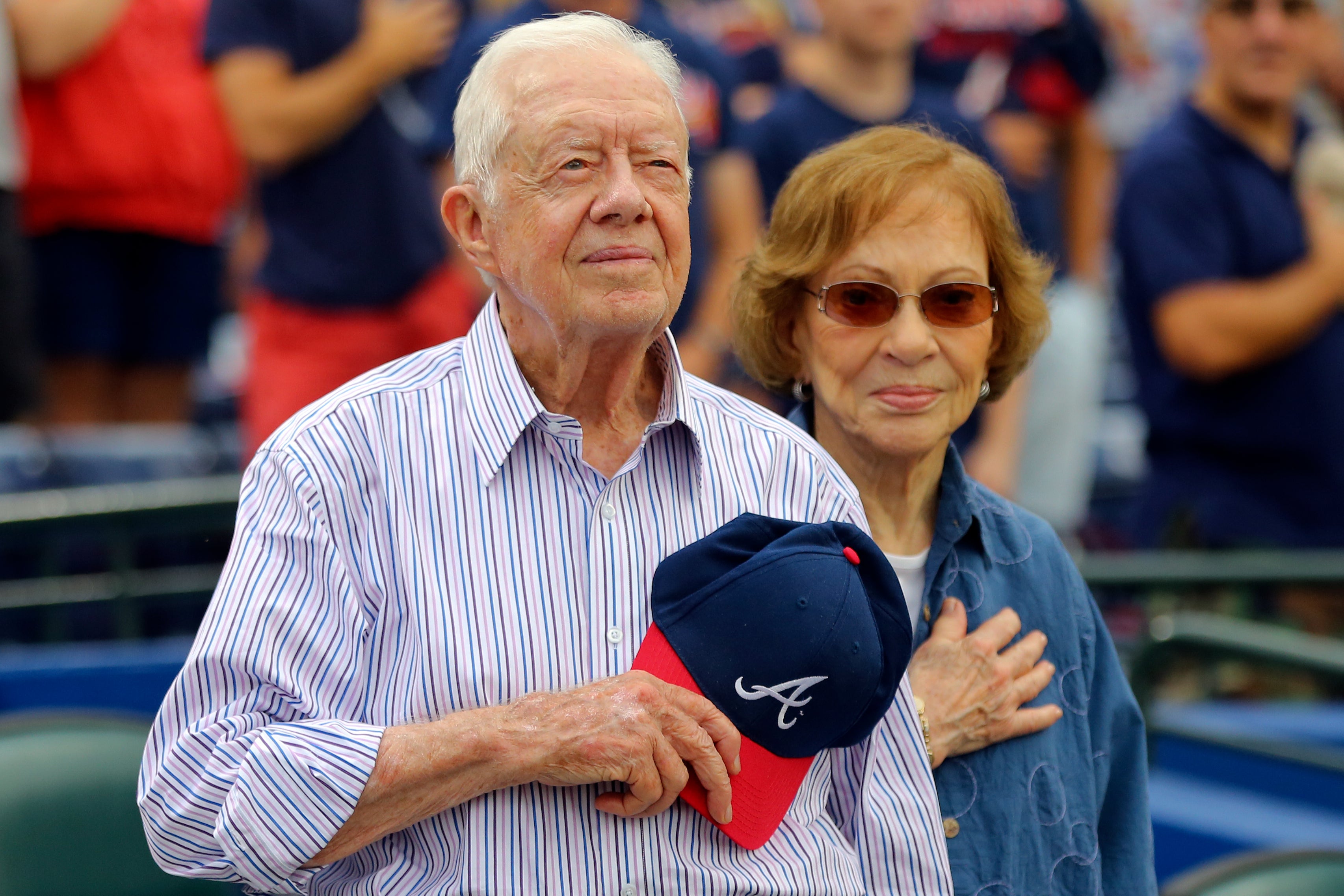

For decades after he was crushed in the 1980 presidential election, Jimmy Carter was defined as a loser. But, by any standard, he won at life. He was the longest-living American president, the longest married (77 years, and happily), and – especially if you look at his whole career – among the most accomplished and productive figures of our era.

Now it’s time for the public to reassess this inspiring, complex, and confounding man. When I first began researching his epic American life in 2015, I was struck by the ubiquity of the easy shorthand on him – bad president; great former president. Even now, everyone from political scientists to the average person on the street will express this idea as if it’s an established fact. The problem is, the widespread conventional wisdom on Carter is mostly wrong.

In His Very Best: Jimmy Carter, a Life, I concluded that Carter was a hugely underrated president – a political failure but a substantive, visionary success. And he was a slightly overrated former president, despite essentially redefining that role. In the four decades since leaving office in 1981, he achieved several important things (especially in global health) but had much less power to change lives than he did while in office.

The Jimmy Carter I got to know – in Atlanta (site of the Carter Library and Carter Centre), Plains (his birthplace and lifelong home), by extensive email exchanges, building a house with him and Rosalynn in Memphis – was a highly intelligent and paradoxical man: by turns, warm and chilly; open and opaque; able and tone deaf.

One day I asked Rosalynn – who shared with me his steamy love letters from the navy – if he was stubborn. She just nodded and laughed. I came to think of her husband as a driven engineer labouring to free the humanist within. He once told me that he could only express his true feelings in his poetry.

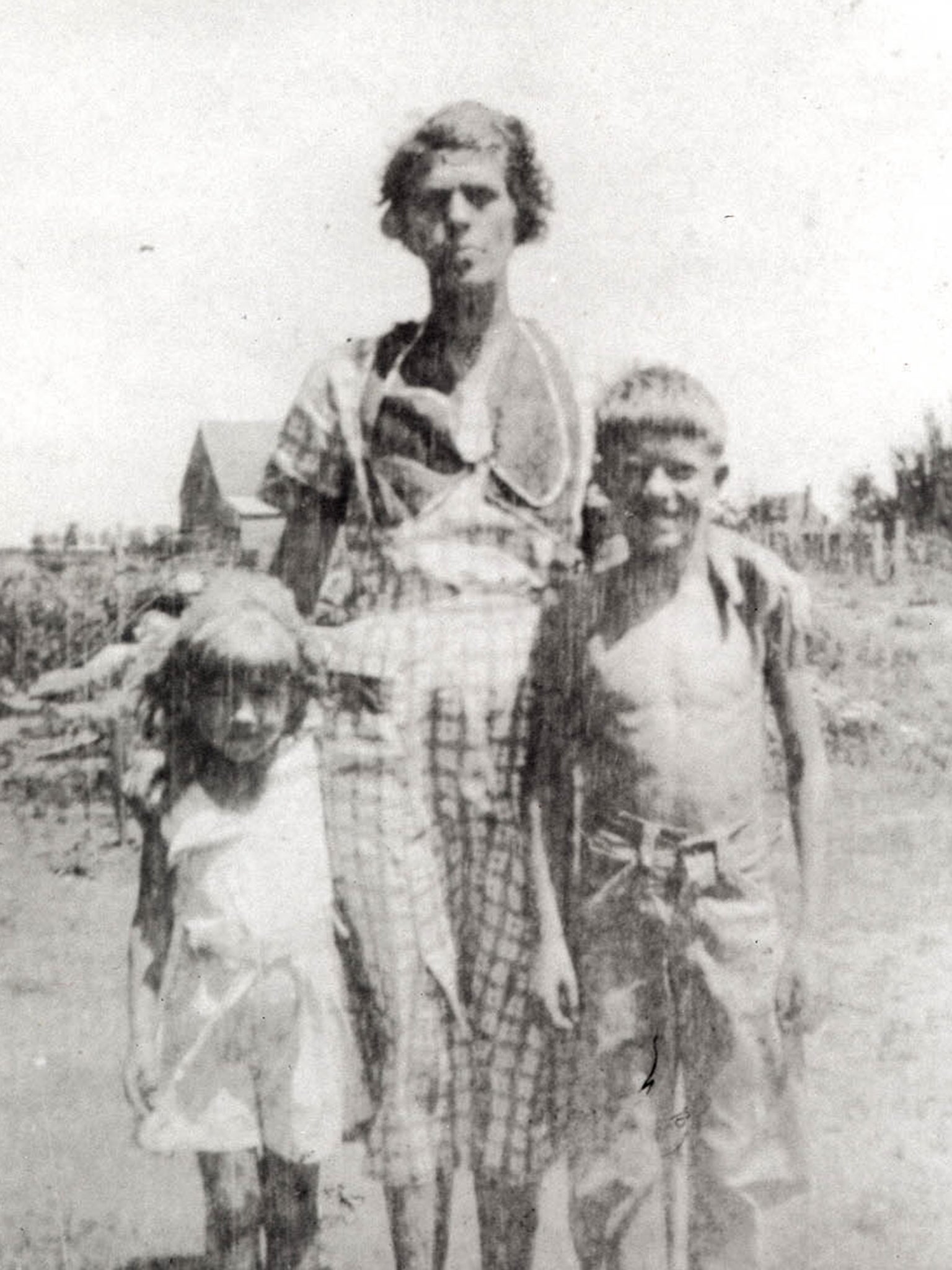

Carter has led an extraordinarily colourful life – full of surprises – and he essentially lived in three centuries. He was born in 1924, but it might as well have been the 19th century – his family, while prosperous for the area, had no electricity, running water or mechanized equipment on the farm.

He was connected to almost all of the major events and movements of the 20th century. Meanwhile, the issues he tackled during his post-presidency – global health, democracy promotion and conflict resolution – are the cutting-edge challenges of the 21st.

His father, Earl, was a white supremacist; his mother, Lillian, was a nurse who took care of Black sharecroppers for free and the only person in the county with anything nice to say about Abraham Lincoln. He was raised mostly by a Black farmhand named Rachel Clark, who gave him a love of nature and God.

As a child, Jimmy – nicknamed Pee-Wee because of his short stature – was driven by a dream of attending the US Naval Academy, from which he graduated in 1946. He was later accepted into the most elite technology program of the mid-20th century – Admiral Hyman Rickover’s nuclear navy – where he helped build one of the prototypes of the first nuclear submarine.

When Earl Carter died in 1953, he decided to leave the navy and return home to take over his father’s peanut warehouse. Rosalynn was so unhappy that she gave him the silent treatment all the way from upstate New York to southwest Georgia. (“Jack,” she told their six-year-old, “tell your father he needs to stop at a rest area.”)

Faith was an essential part of Carter’s life. In 1968, he underwent a slow born-again experience that included door-to-door Baptist missionary work in Massachusetts and Pennsylvania. He even tried – and failed – to convert the madam of a brothel. But once he reached high office he became a strong supporter of a strict separation of church and state.

Carter was elected to the Georgia state senate in 1962 (after a local county boss literally stuffed the ballot box in an effort to steal the election from him) and he ran unsuccessfully for governor in 1966 as a (relative) liberal.

At that point, he decided that he could either be governor or be an outspoken advocate of civil rights – but not both. So while he campaigned a bit in Black churches and never said anything explicitly racist, his second, successful try – in 1970 – included dog-whistle appeals to segregationists.

Just moments after being sworn in as governor, Carter in his inaugural address announced that the time for racial discrimination was over. Many white supporters felt betrayed, while Black Georgians left the inauguration shocked but hopeful.

Carter then began using the second half of his life to make up for what he did not do in the first half – namely, stand up for civil rights. He integrated Georgia’s state government and hung Martin Luther King’s portrait in the state capitol, while also amassing a highly impressive environmental record and challenging Georgia’s criminal justice system.

After leaving office in early 1975, he launched a brilliant presidential campaign that – with the help of the Watergate scandal and the support of “Gonzo” journalist Hunter S Thompson – brought him from zero per cent in the polls to the Democratic nomination. While briefly derailed by an interview in Playboy magazine in which the Southern Baptist confessed to having “lusted in my heart”, he won a narrow victory in 1976 over incumbent Gerald Ford, who had assumed the presidency after the resignation of Richard Nixon.

With skills ranging from agronomist, land-use planner, nuclear engineer and sonar technologist to poet, painter, Sunday school teacher and master woodworker, Carter was the first president since Thomas Jefferson who could rightly be considered a Renaissance man.

He was also the first since Jefferson under whom no blood was shed in war. And his record of honesty and decency – once seen as minimum qualifications – have loomed larger with time. At a farewell dinner just before leaving office, his vice-president, Walter F Mondale, whose job Carter turned from punchline into a position of real responsibility, toasted the Carter administration: “We told the truth. We obeyed the law. We kept the peace.” Carter later added a fourth major accomplishment: “And we championed human rights.”

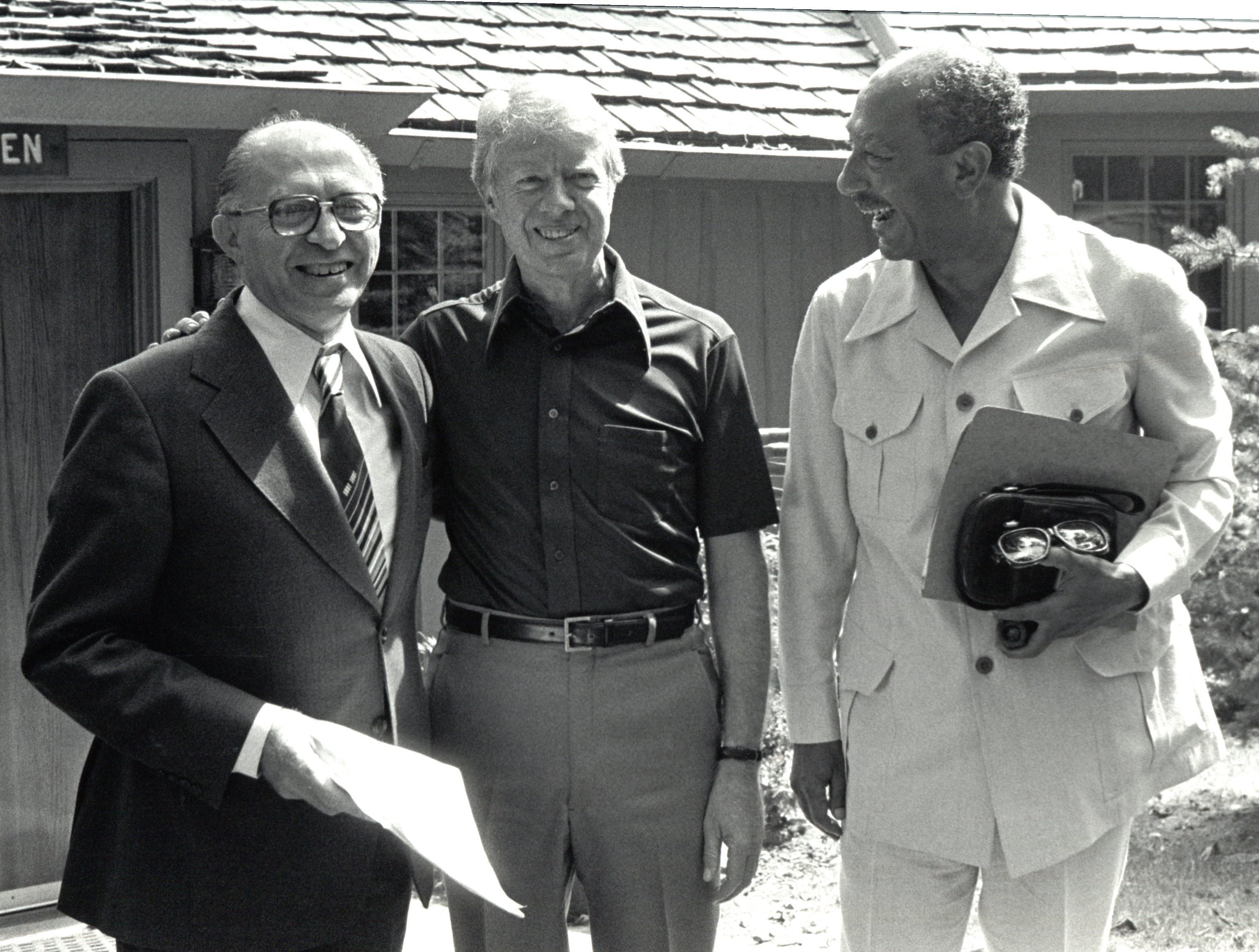

Carter may be best known for the 1978 Camp David Accords, the most durable major peace treaty since the Second World War. Israel and Egypt had fought four wars in 30 years when Carter brought Israeli prime minister Menachem Begin and Egyptian president Anwar Sadat together for 13 days of talks at a rustic retreat in the Maryland mountains.

At various moments, Begin and Sadat (a close friend of Carter) packed their bags and prepared to leave without an agreement. The deal was saved by Carter’s grit, which he showed again six months later when he went to the Middle East to painstakingly put the whole thing back together again before the White House signing ceremony.

Averell Harriman, who served as Franklin D Roosevelt’s wartime envoy, called Camp David “one of the most extraordinary things any president in history has ever accomplished”.

Carter’s most far-reaching accomplishment may have been the normalization of US relations with China. Nixon opened the door and Carter walked through it. Within days of Deng Xiaoping’s historic 1979 visit to Washington, Deng legalized private property and took other major steps toward a capitalist economy.

Carter jettisoned Nixon and Ford’s awkward “two Chinas policy” (which favoured Taiwan) and established the bilateral relationship that – for all its problems – is the foundation of the global economy.

At home, Carter failed to enact welfare, tax and healthcare reform. But he still signed more domestic legislation than any other post-war president except Lyndon Johnson, much of it far-sighted.

He established the Department of Education, the Department of Energy, and the Federal Emergency Management Agency; replaced tokenism with genuine racial and gender diversity in the civil service (which he revamped for the first time in 100 years) and federal judiciary; curbed the power of banks to “redline” (disinvest in) Black neighbourhoods; and provided the first whistleblower protections and the first bureaucratic watchdogs (inspectors general).

Carter revolutionised not just the vice-presidency but the role of first lady, giving Rosalynn her own staff, diplomatic missions and authority; it was Rosalynn who convinced the vast majority of states to require public school children to be vaccinated against polio, measles, mumps and other diseases.

As in Georgia, Carter was far ahead of his time on energy and the environment. He placed solar panels on the roof of the White House (later taken down by Reagan), a symbol of a stellar record that included the first funding for green energy, the first fuel economy standards for autos, the first incentives for public utilities to use renewable energy, and the first federal requirements for toxic waste clean-up, among other far-reaching statutes.

With the Alaska Lands Bill, Carter protected that state from being despoiled and doubled the size of the national park system. Had he been re-elected, he planned to begin to address global warming, which was then an obscure problem even in the scientific community.

In the second half of his term, Carter was beset by external problems, many of them beyond his control. Gasoline shortages led to a public “malaise” (which Carter addressed in a famous speech, without using the word).

Senator Edward Kennedy, the darling of liberals, launched a damaging campaign against him for the 1980 Democratic nomination. After the seizure of the hostages in Tehran, the American public rallied around Carter for a time, which helped him fend off Kennedy. But when an April 1980 helicopter mission to free the hostages was aborted in the Iranian desert, Carter’s popularity sunk again – and his failure to unite his party after the Kennedy challenge didn’t help. After Reagan turned to the cameras in their only debate and asked, “Are you better off than you were four years ago?” the election was effectively over.

After leaving office, Carter wrote his memoirs and began devoting a week a year to building a house for Habitat for Humanity, helping spread the word about a small non-profit just up the road from Plains that eventually became the largest non-profit builder of housing in the world.

But Carter was depressed and at loose ends. One night in 1982, he woke up with a start and realised that he should build a conference centre to bring peace between warring parties, as he had at Camp David. Carter’s major diplomatic successes both came in 1994, when (over President Clinton’s objections) he negotiated peace with Kim Il Sung, the founder of North Korea, and – along with Colin Powell and Sam Nunn – prevented a war in Haiti.

Over time, the Carter Centre, which now employs more than 3,000 people (mostly abroad), has allowed its founder to redefine what we expect from our former presidents. Embracing some form of public service is now the rule, not the exception, for (most of) them. Carter had only limited contact with Donald Trump, who represents the opposite of everything Carter stands for.

The Carter Centre has monitored more than 100 elections around the world but its greatest success has been in global health, especially the near-eradication of Guinea worm disease, which afflicted 3.4 million people when Carter began working on the problem, and now affects only a couple of hundred. He also fought river blindness, Ebola and other diseases, and Rosalynn, who died in November 2023 aged 96, did important work in lifting the stigma of mental illness.

Even after beating melanoma in 2015, Carter continued his work as a peacemaker and promoter of human rights and democratic accountability. And he taught Sunday school at Maranatha Baptist Church in Plains until he was 95.

In recent years, the shortcomings and contradictions of his long life have given way to an appreciation of his core decency. Now, beyond his heavenly reward, we are left with his earthly example: a life of ceaseless effort, not just for himself but for the world he helped shape.

Jonathan Alter is the author of ‘His Very Best: Jimmy Carter, a Life’

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments