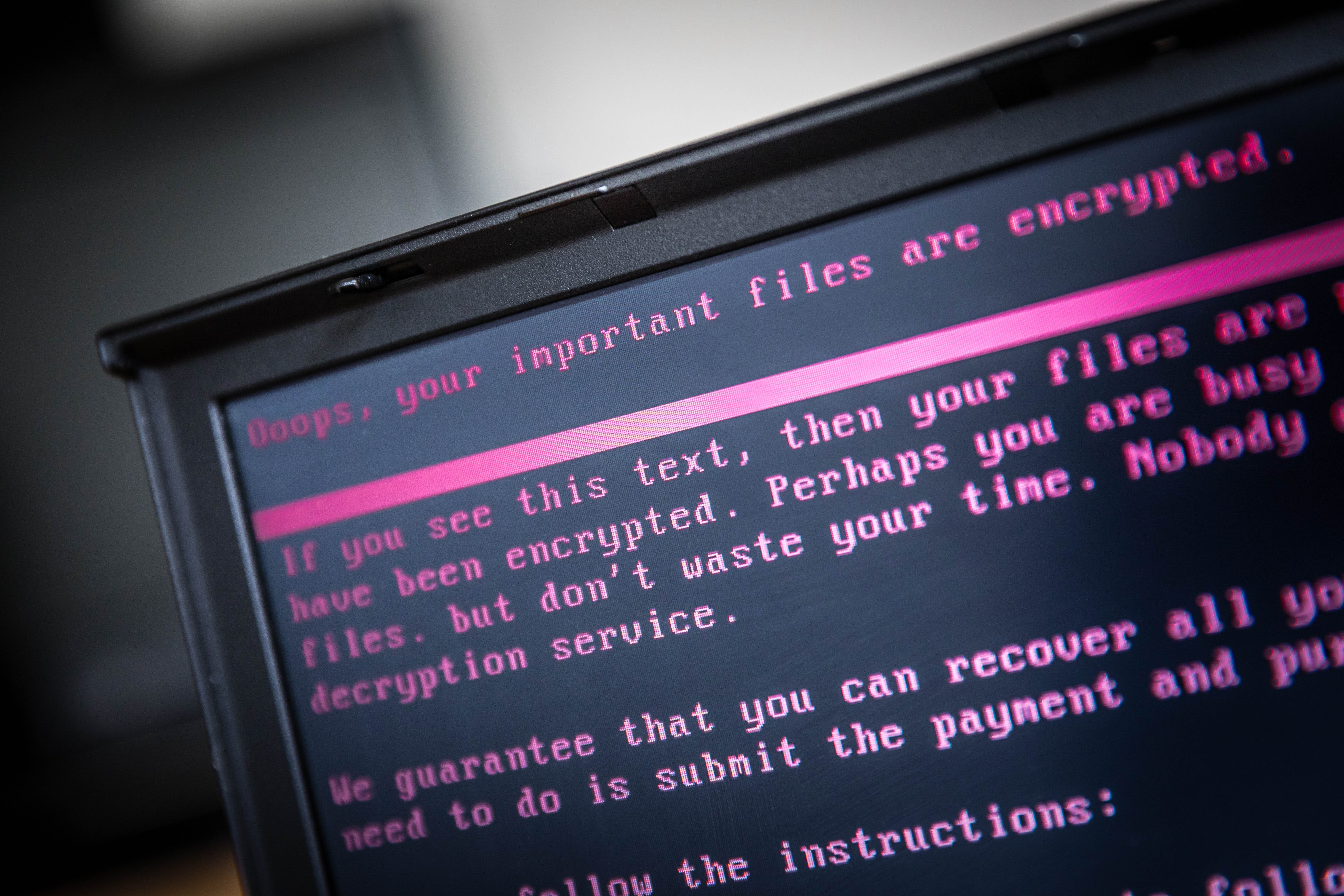

Hospital ransomware attack caused baby’s death by shutting down heart rate display, lawsuit claims

Lawyers for Teiranni Kidd accused Springhill Hospital in Alabama of negligence over the ‘preventable’ death of her daughter Nicko during a cyberattack

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.An Alabama woman whose baby died during a ransomware attack on the hospital where she was giving birth has sued the institution for negligence and wrongful death.

In court papers filed last June, lawyers for Teiranni Kidd of Mobile, Alabama accuse Springhill Memorial Hospital and its parent company of not doing enough to prevent the cyberattack and of conspiring to hide its severity.

Ms Kidd’s daughter, Nicko, was born in July 2019 with her umbilical cord wrapped around her neck, which elevated her heart rate, gave her severe brain damage, and led to her death nine months later.

The problem normally have been visible on a large screen at the central nurses’ station, but that system had been locked down by hackers demanding a ransom payment, leaving only a paper print-out at Ms Kidd’s bedside to register the danger.

“Teiranni Kidd... was not told that the hospital's computer systems had been hacked, that they were not operating as needed, and that patient safety was implicated and could be compromised,” the lawsuit says.

It then describes how the ransomware shut down the hospital’s computer systems for days on end, forcing nurses and doctors to use outdated paper heartbeat charts and hand-delivered documents.

“Nurses and other healthcare personnel were forced to use outdated paper charting methods and paper documentation to record and document Teiranni’s labour and Nicko's delivery,” it says.

“Some of the paper forms used outdated terminology and had not been used in years...

“As a result, the number of healthcare providers who would normally monitor her labour and delivery was substantially reduced, and important safety-critical layers of redundancy were eliminated.”

The suit contends that if Ms Kidd had known the extent of the cyberattack she would have chosen to have her baby elsewhere.

Ms Kidd’s complaint, first reported by The Wall Street Journal on Thursday, was originally filled in January 2020 and amended that June after Nicko’s death.

If her claims are proven, it would be first death conclusively tied to ransomware attacks, which have sown chaos around the world by shutting down computer systems in hospitals, transport networks, gas pipelines and beyond.

Springhill Hospital denies any wrongdoing. Its chief executive Jeffrey St Clair told the Journal that it had stayed open because patients needed its services and its physicians had deemed it safe to do so.

According to the Journal, court documents show how Springhill medics scrambled to keep their hospital running in the wake of the attack, which had reportedly been running for eight days when Ms Kidd arrived.

“We have no computer charting for I don’t know how long,” one manager said. “I want to run away,” said a nurse in a text message.

Jeffrey Planchard, an anaesthesiologist who worked at Springhill during the outage, told the Journal that losing access to medical records “put lives at risk”.

He said that usually, nurses would “instinctively” check the main screen throughout the day, but instead it fell to a single nurse on Ms Kidd’s ward to notice the problem on printouts from a bedside heart rate monitor.

In the aftermath of Nicko’s birth, text messages published by the Journal show Katelyn Parnell, the attending obstetrician, telling the nurse manager: "I need u to help me understand why I was not notified."

To another colleague, she texted: “It just sucks. Totally preventable. I know bad things happen and sometimes you can't control it, but this was preventable.”

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments