Haiti prime minister resigns as new government takes shape to lead country gripped by deadly gang violence

More than 2,500 people have been killed or injured in the last few months, UN data says

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Haiti's prime minister has resigned, clearing the way for a new government to be formed in a country that has been wracked by widespread gang violence.

More than 2,500 people were killed or injured from January through March, data from the UN shows.

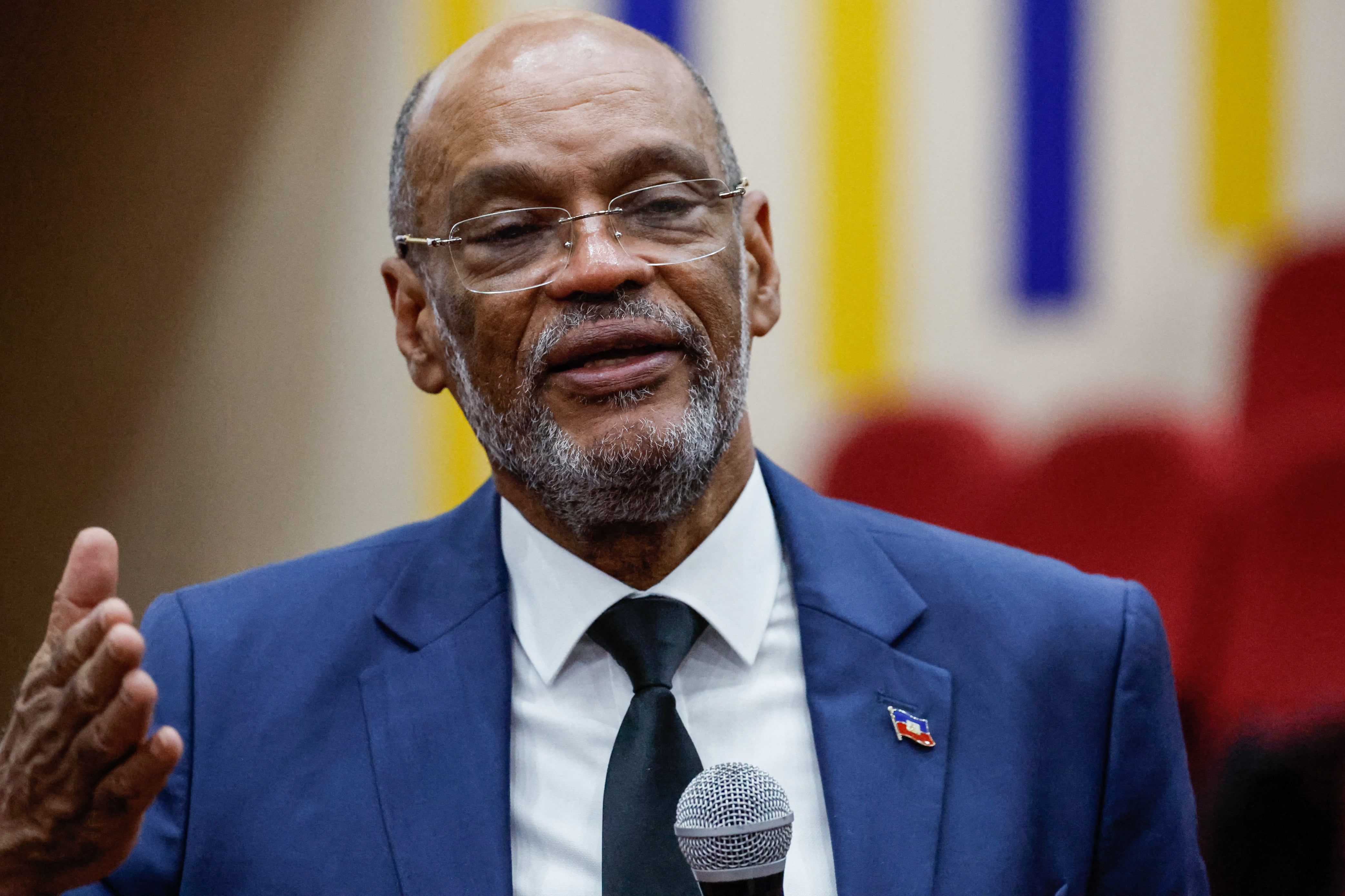

Ariel Henry presented his resignation in a letter signed in Los Angeles, dated 24 April, and released on Thursday by his office on the same day that a council tasked with choosing a new prime minister and cabinet for Haiti was sworn in.

Henry’s remaining cabinet meanwhile chose economy and finance minister Michel Patrick Boisvert as the interim prime minister. It was not immediately clear when the transitional council would select its own interim prime minister.

The council was installed more than a month after Caribbean leaders announced its creation following an emergency meeting to tackle Haiti’s spiraling crisis. Mr Henry had pledged to resign once the council was installed.

The nine-member council, of which seven have voting powers, is also expected to help set the agenda of a new cabinet. It will also appoint a provisional electoral commission, a requirement before elections can take place, and establish a national security council.

The council’s non-renewable mandate expires on 7 February 2026, at which date a new president is scheduled to be sworn in.

Gangs launched coordinated attacks that began on 29 February in the capital, Port-au-Prince, and surrounding areas. They burned police stations and hospitals, opened fire on the main international airport that has remained closed since early March and stormed Haiti’s two biggest prisons, releasing more than 4,000 inmates. Gangs also have severed access to Haiti’s biggest port.

The onslaught began while Mr Henry was on an official visit to Kenya to push for a UN-backed deployment of a police force from the East African country. He remains locked out of Haiti.

“Port-au-Prince is now almost completely sealed off because of air, sea and land blockades,” Catherine Russell, Unicef’s executive director, said earlier this week.

The international community has urged the council to prioritize Haiti’s widespread insecurity. Even before the attacks began, gangs already controlled 80 per cent of Port-au-Prince. The number of people killed in early 2024 was up by more than 50 per cent compared with the same period last year, according to a recent UN report.

“It is impossible to overstate the increase in gang activity across Port-au-Prince and beyond, the deterioration of the human rights situation and the deepening of the humanitarian crisis,” Maria Isabel Salvador, the UN special envoy for Haiti, said at a UN Security Council meeting on Monday.

Nearly 100,000 people have fled the capital in search of safer cities and towns since the attacks began. Tens of thousands of others left homeless after gangs torched their homes are now living in crowded, makeshift shelters across Port-au-Prince that only have one or two toilets for hundreds of residents.

“Although I’m physically here, it feels like I’m dead,” said Rachel Pierre, a 39-year-old mother of four children.

“There is no food or water. Sometimes I have nothing to give the kids,” she said with her 14-month-old in her arms.

Many Haitians are angry and exhausted at what their lives have become and blame gangs for their situation.

“They’re the ones who sent us here,” said Chesnel Joseph, a 46-year-old math teacher whose school closed because of the violence and who has become one of the shelter’s informal directors. “They mistreat us. They kill us. They burn our homes.”

Associated Press

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments