Guerrilla girl power: Have America's feminist artists sold out?

Have America's most famous feminist artists finally sold out to the establishment? Guy Adams reports from Los Angeles

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

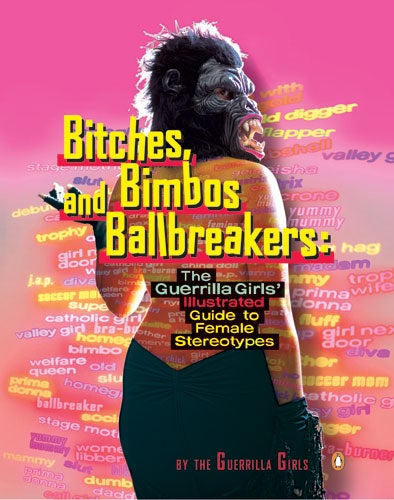

Your support makes all the difference.After a quarter of a century railing against the dusty establishment, the art world's most prominent group of radical feminists has decided to join it. The Guerrilla Girls, a collection of radical, left-leaning pop artists famed for wearing gorilla masks and fishnets to highlight sexism, racism, and other pillars of injustice, announced this week that its historic archive will be kept, for posterity, by the bluest of America's blue-chip cultural institutions.

Forty boxes of material from the group's headline-grabbing career, which began in earnest in the 1980s, when it covered New York with posters asking "Does a woman have to get naked to get into the Met?", have been acquired by the Getty Research Institute in Los Angeles.

"We've been keeping this stuff in boxes in a storage room in New York for years, and have been thinking about doing something with it for a long time," explained Kathe Kollwitz, a founding member of the group, whose members assume the identities of dead female artists to maintain anonymity. "It's mostly correspondence, photos, fan mail, hate mail, sketches, notes on projects, and drafts of some of our books. We are now taught in many universities as part of art history and sociology courses and the Getty will be able to properly catalogue it and put it online to make it accessible."

For the Research Institute – founded by the extraordinarily wealthy (and distinctly male) oil tycoon Jean Paul Getty – to be entrusted with the subversive group's archive may seem at best counter-intuitive, and at worst downright hypocritical. But the Guerrilla Girls have always trod a fine line between radicalism and the mainstream. Since 1985, when they began producing their trademark brand of provocative protest posters, badges and leaflets, they have been lauded by the very establishment they seek to undermine. In recent years, the Guerrilla Girls have exhibited at the Tate Modern in London, and the Venice Biennale. Later this year, their work will be exhibited at the Pompidou Centre in Paris.

The group was formed in 1985, when a dozen like-minded female activists picketed the Museum of Modern Art in New York, where an exhibition claiming to be a "definitive" survey of contemporary painting and sculpture included just 13 women in its 169 featured artists. Few people paid any attention to that protest. So the group's members decided on a new tack: they began wearing gorilla masks, and flyposting Manhattan with hundreds of smartly designed black and white posters outlining their various beefs.

The typical Guerrilla Girls poster, which they've been producing variations of ever since, contains a selection of statistics and bold headlines that level charges of racism or sexism at various quarters of the arts world, from white, male critics and artists to galleries and museums.

Their first poster, produced in 1985, listed 42 contemporary artists. "What do these artists have in common?" it asked. Answer: "They all allow their work to be shown in galleries that show no more than 10 percent women, or none at all". Other early works railed at the tendency of collectors to pay more for work by male artists than that of their female contemporaries. "When racism and sexism are no longer fashionable, what will your art collection be worth?" asked one.

The group attracted a wealth of criticism in the early years. New York Times critic Hilton Kramer dubbed the Guerrilla Girls "quota queens". Art dealer Mary Boone described their campaigns as "an excuse for the failure of talent". But the public loved them. Initially, the posters were printed in batches of 500, and plastered up by gorilla-mask-clad activists in the dead of night. But soon they began to attract acclaim, and collectors gobbled them up, providing the group with the funds to get their works on giant billboards.

"We're trying to change people's minds by using facts that they maybe won't have seen and presenting them in an interesting way," Kollwitz said in an interview yesterday. "What we do is humorous. It's satire. A lot of political art points at something and says 'This is bad'. We are trying to find a funny way of doing the same thing. Humour has always been part of the ticket. One of our goals has always been to confound the notion of what feminism is. Everyone hates to see women complain. But I think we have found a way to do it so that no one complains."

In the 1990s, they branched out into the world of politics, with posters railing against rape laws, and the religious right. Recent targets include George W Bush and Arnold Schwarzenegger. "Don't let your Governor grope you" proclaimed a cut-out "Schwarzenegger shield" they produced. In 2002, they took out a large advert during Oscar season, featuring an "anatomically correct Oscar statue" – a podgy, white man clutching his genitals. Next to the picture was the observation that no woman had ever won the "Best Director" award.

Today, the number of Guerrilla Girls members remains a secret. Kollwitz says that over the years, between 50 and 70 people have been involved, but only about a dozen are active at any one time. As to accusations of selling out, Kollwitz is anxious to stress that none of the organisation's members will directly profit from the sale of the group's archives. "We don't need money. We just need bananas," she says. "Seriously, though, we all have other careers."

Getty trumpeted its acquisition yesterday, saying in a press release that the archive would "be useful in understanding the second phase of feminist art history". The acquisition may suggest that at least part of the Guerrilla Girls' work is done, but Kollwitz isn't about to hang up her gorilla mask. "The art world still has a lot of issues, so there's plenty for us to carry on protesting about," she said. "Culture likes to think of itself as avant garde, when really, it is still very derrière."

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments