Abraham Lincoln's Gettysburg Address: The 'greatest speech in the world' – that was only 273 words long

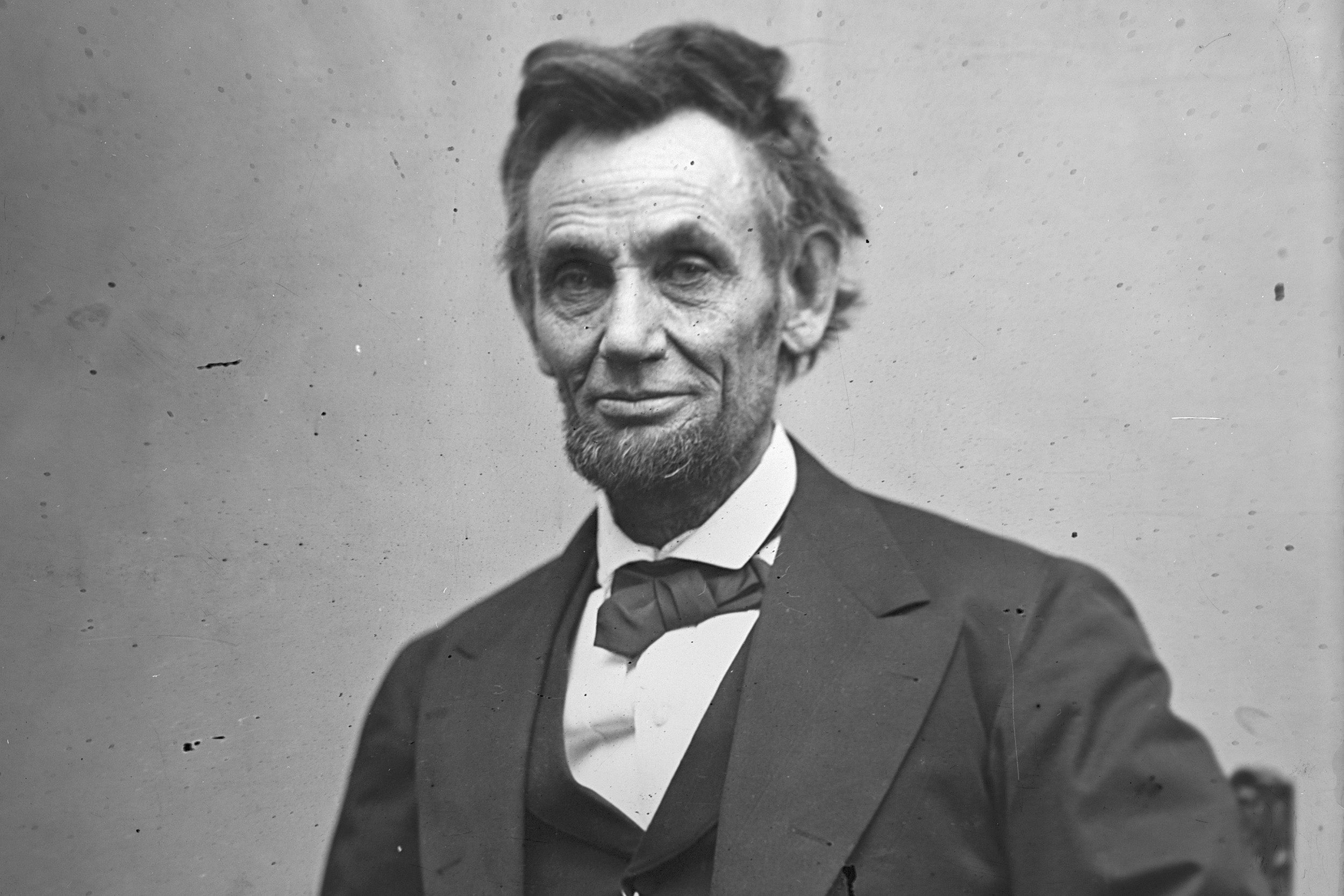

President Abraham Lincoln delivered the Gettysburg Address on November 19, 1863

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Delivered on the site of one of the bloodiest battles of the Civil War, the Gettysburg Address is known by some as the greatest speech in the world – and one of Abraham Lincoln's defining moments.

Four months earlier, 46,000 soldiers from both sides of the Civil War had been killed or wounded in the Battle of Gettysburg, in Pennsylvania.

The 273 words delivered by Lincoln at the official dedication ceremony for the National Cemetery at the site on November 19, 1863, called upon the fundamental principles of the Declaration of Independence and the Union's ideals – "a government of the people, by the people, for the people".

The speech's legacy and lasting impact has seen American schoolchildren throughout the years taught to recite the historical phrasings, while subsequent presidents are also said to have used the speech as a map for governance in the US.

The exact words Lincoln spoke at the dedication ceremony cannot be verified for certain, although there are five known copies in the former president's handwriting, according to Abraham Lincoln Online.

Of those, the most often reproduced, including on the walls of the Lincoln Memorial in Washington, is the Bliss Copy - named after Colonel Alexander Bliss, as seen below...

Four score and seven years ago our fathers brought forth on this continent, a new nation, conceived in Liberty, and dedicated to the proposition that all men are created equal.

Now we are engaged in a great civil war, testing whether that nation, or any nation so conceived and so dedicated, can long endure. We are met on a great battle-field of that war. We have come to dedicate a portion of that field, as a final resting place for those who here gave their lives that that nation might live. It is altogether fitting and proper that we should do this.

But, in a larger sense, we can not dedicate — we can not consecrate — we can not hallow — this ground. The brave men, living and dead, who struggled here, have consecrated it, far above our poor power to add or detract. The world will little note, nor long remember what we say here, but it can never forget what they did here. It is for us the living, rather, to be dedicated here to the unfinished work which they who fought here have thus far so nobly advanced. It is rather for us to be here dedicated to the great task remaining before us — that from these honored dead we take increased devotion to that cause for which they gave the last full measure of devotion — that we here highly resolve that these dead shall not have died in vain — that this nation, under God, shall have a new birth of freedom — and that government of the people, by the people, for the people, shall not perish from the earth.

Abraham Lincoln

November 19, 1863

Subscribe to Independent Premium to bookmark this article

Want to bookmark your favourite articles and stories to read or reference later? Start your Independent Premium subscription today.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments