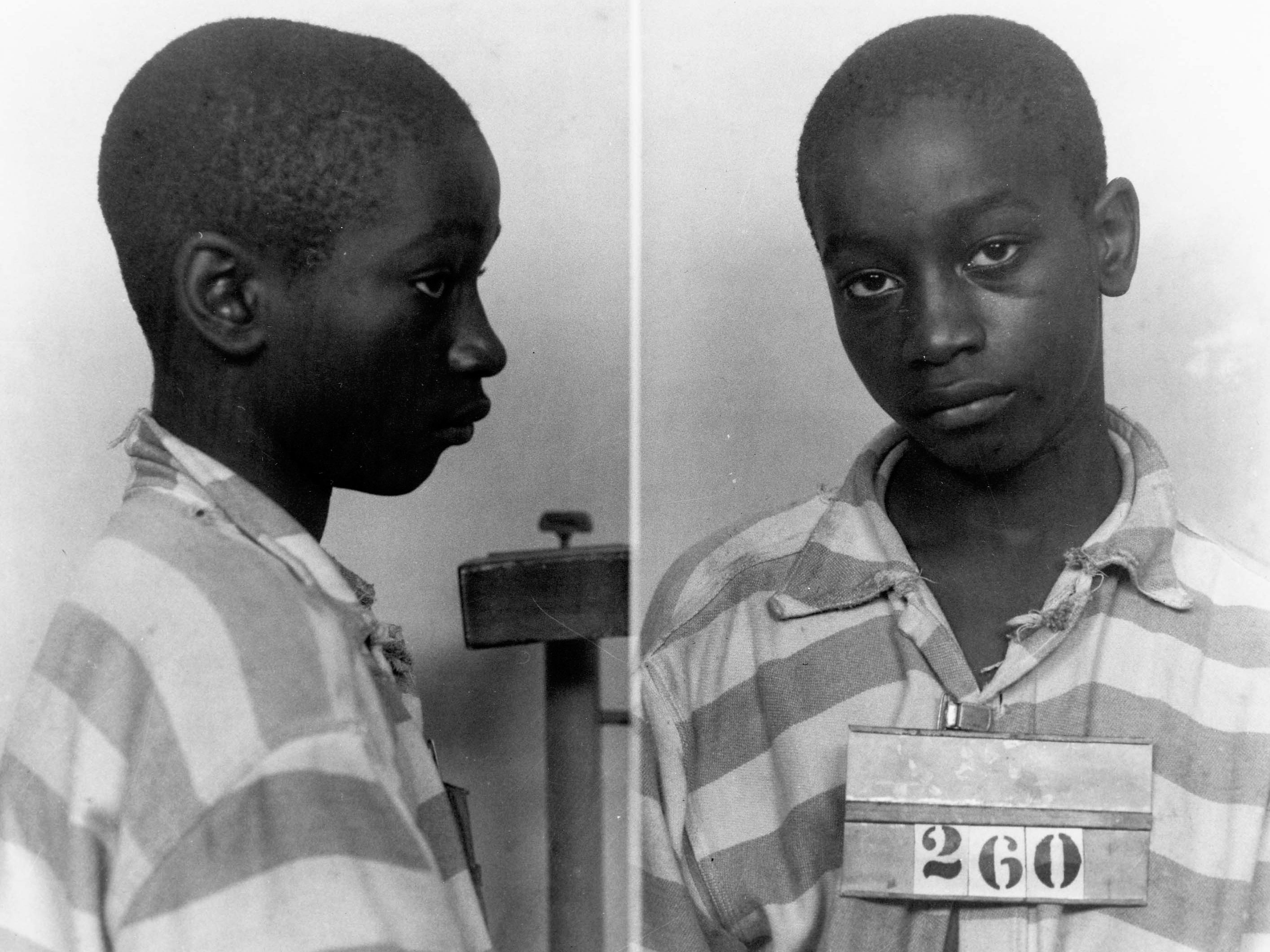

George Stinney Jr: Black 14-year-old boy exonerated 70 years after he was executed

George Stinney Jr’s conviction was overturned because he was not given a fair trial

George Stinney Jr became the youngest person to be executed in the US in the 20th century when he was sent to the electric chair in 1944, but more than 70 years after his death his conviction has been overturned.

Circuit Judge Carmen Mullen said the speed with which the state meted out justice against the boy was shocking and extremely unfair, and that his case was one of "great injustice" in her ruling exonerating Stinney Jr.

The 14-year-old black boy was sentenced to death for the murder of two white girls in a segregated mill town in South Carolina, in a trial that lasted less than three hours and reportedly bore no evidence and barely any witness testimonies.

He was kept from his parents and any legal counsel when he was interrogated by authorities, and his supporters claim that the small, frail boy was so scared that he would have said whatever he thought would make the police happy, despite there having been no physical evidence linking him to the death of the girls.

Stinney Jr and his sister Amie Ruffner were the last people to see the two girls, aged 7 and 11, alive when they were out in a field near the town of Alcolu. Stinney Jr’s father had been part of the search team that found the girls’ bodies hours later in a ditch, badly beaten with crushing blows to their skulls.

Stinney Jr had been arrested and executed within the space of around three months. Executioners noted that he was too small for the electric chair when he died; the straps did not fit him, an electrode was too big for his leg, and the boy had to sit on a bible to fit properly in the chair.

His case has long been spoken of as an example of how a black person could be railroaded by a justice system during the era of Jim Crow segregation laws where the investigators, prosecutors and juries where all white.

The boy’s family have insisted that he was innocent, and in January they asked a local judge to order a re-trial and clear Stinney Jr’s name, claiming there was new evidence about the crime.

This time Stinney Jr’s case was given a two day hearing in which experts questioned his confession and the autopsy findings, while the judge heard accounts from the boy’s surviving brothers and sisters, and someone who had been involved in the search. Most of the evidence from the original trial was gone and almost all the witnesses were dead.

It took Mullen nearly four times as long to return her decision on Stinney Jr’s case than it had originally taken to arrest and have him executed in 1944, and said in her ruling that she could “think of no greater injustice” than the boy’s case.

Judge Mullen found that Stinney Jr’s confession was “highly likely” to have been coerced by authorities, while few or no witnesses were found to have testified in the trial.

The judge said she was overturning the boy’s conviction because the South Carolina court had failed to grant a fair trial in 1944.

Additional reporting by AP

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments