‘There’s a charge in the air’: Houston says goodbye to George Floyd, but vows to fight on

‘The atmosphere has changed. I think people have realised it can’t go on like this,' Richard Hall hears in Texas

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.When George Floyd was a young man growing up in Houston, he told his friends that he wanted to change the world. As he returned home today, there was no doubt that he had.

His name rings out in the streets of London and Paris. His face appears on murals on the walls of Syria’s ruined cities. Hundreds of thousands of people have marched in his memory in cities and small towns across America.

The world has mourned for George Floyd, but today it was the turn of the city that raised him.

“Looking at George in that casket was like a stab in the chest, because he didn’t have to die,” said Raheem Smith, 37, a friend of Floyd’s. “They could have let him up. ‘I can’t breathe. I can’t breathe. Let me up, please. Mama.’ He called for his mama twice and his mama’s been dead for two years.”

“His death was the straw that broke the camel’s back,” he added. “They didn’t listen to us protest when they killed Eric [Garner]. They didn’t listen to us protest when they killed Philando [Castile], Tamir [Rice] and Trayvon Martin.”

Mr Smith was among thousands who lined up in the hot Houston sun to say goodbye to Floyd at a solemn public memorial on Monday. Young and old, black and white, rich and poor came to pay their respects to a man who, in death, sparked the largest demonstrations for racial justice the country has ever seen. Many felt the hand of history on their shoulder as they did so.

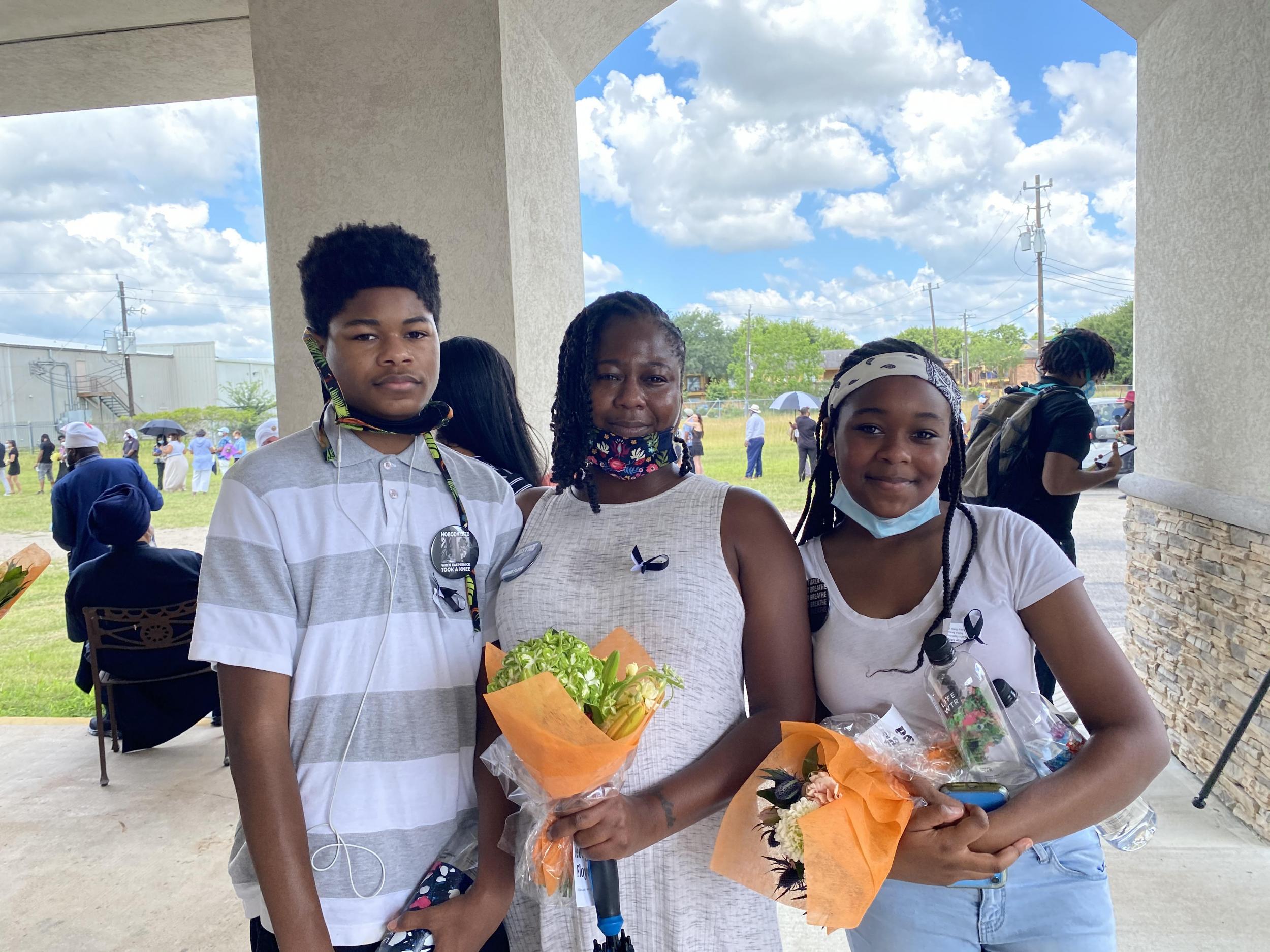

“There’s a charge in the air,” said Ebony Randle, 41, who came with her two teenage children. “The atmosphere has changed. I think people have realised it can’t go on like this.”

“I’m black. What happened to George Floyd could have happened to me or one of my children,” she said. “It’s important for them to be here. I want to teach my children how to protest respectfully, how to stand up for their rights. They couldn’t get a better history lesson.”

Kenneth Beatty, 56, also brought his youngest son and nephew to the memorial. “I wanted to come here today to etch his casket into my memory. I needed to see it.”

Floyd, 46, was killed by a Minneapolis police officer two weeks ago. That officer, Derek Chauvin, put his knee on Floyd’s neck for more than eight minutes as his colleagues stood by. Floyd’s persistent plea to the officer as he lay dying – “I can’t breathe” – has become a rallying cry in massive demonstrations around the world.

Few places have been as charged as Houston by his death. The city has been transformed. Some 60,000 marched peacefully last week to demand justice for Floyd and for all black Americans after hundreds of years of racial inequality.

Memorial services have already been held in North Carolina, where he was born, and Minneapolis, where he died. But it was Houston that knew “Big Floyd” best.

Floyd was raised in Houston’s Third Ward, a sprawling, historically black neighbourhood in the south of the city. The area was once home to ballrooms and blues clubs and a thriving middle class. Just a few blocks from where Floyd lived, there is a marker on the spot where legendary bluesman Lightnin’ Hopkins used to play his guitar. In the 1950s, its wealthier residents began to leave for the suburbs, taking businesses with them. The ward fell behind and pockets of severe poverty took hold.

“It’s a very proud community,” said Mr Beatty. You have the professors from the university there and you had people who were very poor as well.”

Today, the ward is undergoing gentrification, but some 42 per cent of residents still live below the poverty line. The Cuney Homes projects, where Floyd grew up, remains one of the poorest parts of the city. Almost 70 per cent of people in the low-rise neighbourhood live in poverty.

“They called it ‘the bottom’”, said Claudia Blakemore, a 76-year-old retired nurse, as she waited in line to see Floyd’s casket. “It’s a very difficult neighbourhood.”

Floyd’s mother moved there with her three children from North Carolina after separating with Floyd’s father. The family was poor, but Floyd had dreams of escaping his lot. He was a talented athlete — a high school varsity in both American football and basketball.

He was the first in his family to go to college, after winning a basketball scholarship to South Florida Community College. His friends say he wanted to play in the NBA one day, but despite his best efforts he was unable to make it work. When he returned home to the Third Ward without a diploma in 1995, things went downhill.

He was in and out of jail for years, mostly for drug offences. Then in 2007 he pled guilty to a charge of aggravated robbery involving a deadly weapon.

Floyd tried to turn his life around. He turned to religion and community, helping out at local church events and mentoring younger kids from his neighbourhood. Church leaders in the Third Ward described him as gentle and caring.

Still, he struggled with addiction and decided that he would leave Houston to get himself clean and make a fresh start.

His move to Minneapolis was an attempt to turn his life around. A church in the Third Ward that Floyd was familiar with recommended a drug abuse centre in the city that would help him find work.

He was working odd jobs in Minneapolis when he was stopped by officer Chauvin on suspicion of using a counterfeit $20 note.

His death was not unlike the many others that came before him – another unarmed black American killed by police while posing no threat. But it was one too many.

“I woke at 5am the day after he passed to hear his final words,” said Mr Beatty. “I felt like something shifted. This was gonna be different. I didn’t know how I would participate but I wanted to be part of change.”

“I’m a grandfather to three children. It’s my prayer they will never have to protest like this,” said Mr Beatty. “My grandmother and grandfather marched on Washington in 1963 – she passed away at 103 a couple of years ago and I’m sure she didn’t want her grandchildren having to do this,” he adds.

“But seeing this crowd I have hope. I believe we’re all tired of it. A man had to lose his life in such a brutal way but I believe there will be change.”

Ms Blakemore, the retired nurse, said she too was hopeful.

“I was at the march the other day and it was very diverse. Everyone was passionate,” she said.

“There is a lot of anger and sadness. We’ve been through this so many times before. But I do feel like this time is different.”

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments