The long, bitter fight to restore voting rights for 1.5 million former prisoners in Florida

Ahead of the American Workforce and Justice Summit 2022, backed by The Independent, Josh Marcus talks to activists trying to overcome the obstacles to voting faced by thousands of Floridians

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

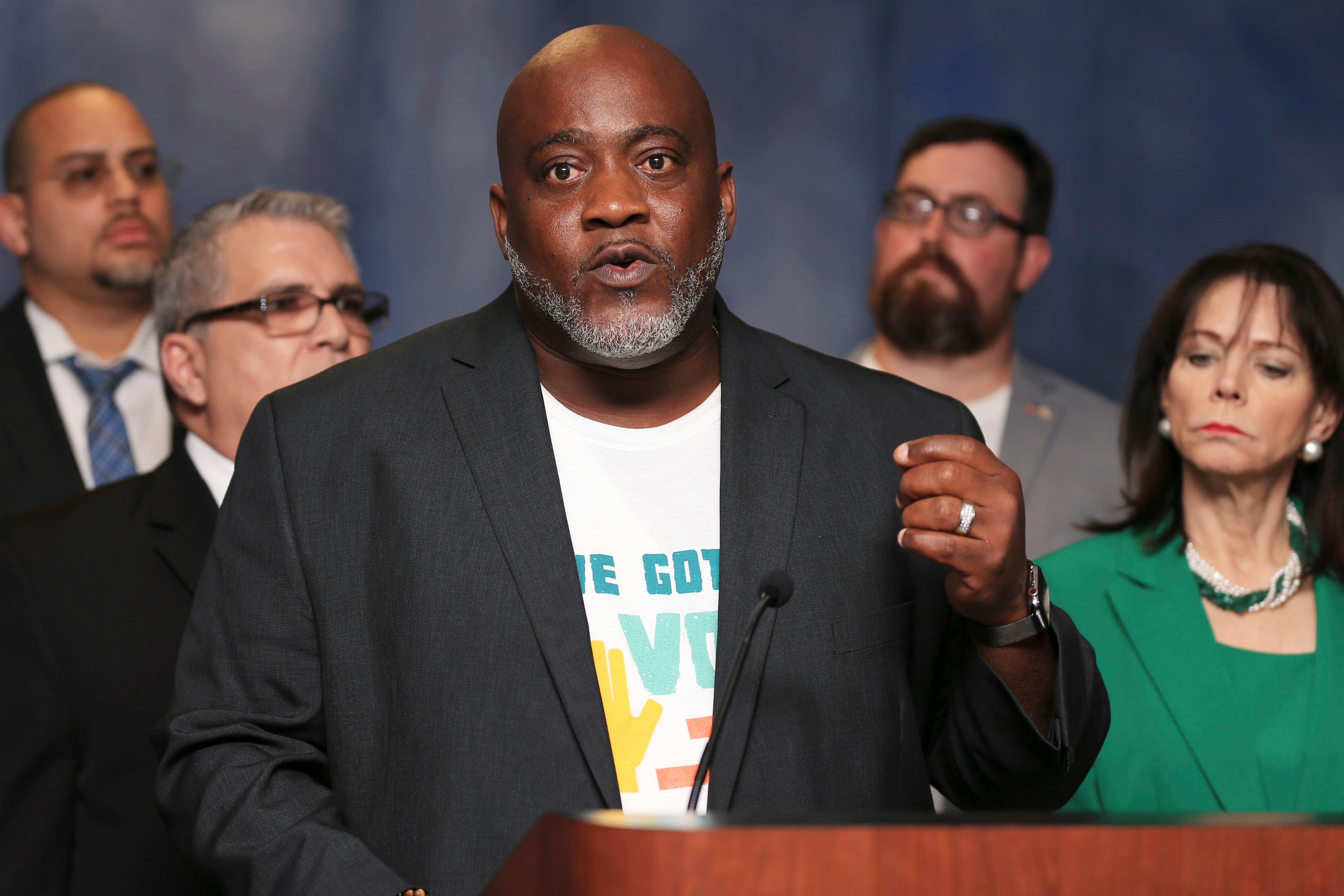

Your support makes all the difference.Desmond Meade, a nationally acclaimed voting rights activist based in Florida, can only remember two people who have disagreed with his push to restore voting rights for people with felony convictions.

One was a preacher Mr Meade met at a biker bar in a conservative county. Another was a Trump supporter he spoke with at a tailgate party for the NFL’s Jacksonville Jaguars. The man claimed his son, who had a felony conviction on his record, was “too damn stupid” to vote.

“Every other time, no matter if the person was white, Black, Spanish, no matter where I was in the state of Florida — whether it was biker bar or a coffee shop or a community center, a library — it didn’t matter where I was or who talked to,” he told The Independent. “I would go and ask them if they knew anyone they loved who ever made a mistake. Once they said yes, I had ‘em. I had ‘em. Now, our conversation is on a personal level and not on a political level. Do you think they should get a second chance?”

In 2018, over five million Floridians agreed, passing Florida’s Amendment 4 ballot initiative with 64 per cent of the vote, including about one million people who voted for Republican governor Ron DeSantis. The campaign, with support ranging from the ACLU to the Koch brothers, was the largest extension of voting rights in the US in half a century, and would allow as many as 1.6 million formerly incarcerated people access to the franchise. Or at least, that was the plan.

Mr Meade’s own life — returning from prison, battling homelessness and addiction, then eventually earning a law degree — showed in astounding form what impact people could make when redemption was possible.

His organisation, the Florida Rights Restoration Coalition (FRRC) showed that there was a massive non-partisan appetite to make voting easier. But the years that followed their stunning successes would see the state, led by Republicans, block many of Amendment 4’s most substantial impacts, and would prove that in America, the battle for voting access is far from over.

Before Amendment 4 passed, Florida’s constitution barred people with felony records from voting unless they successfully petitioned state officers to win their rights back in a lengthy review process. The provision had explicitly racist roots: in 1868, after the Civil War ended, and US constitutional amendments passed ending slavery and granting US citizens equal protection, regardless of race, Florida passed a state constitution that barred people with felony convictions from voting.

A hundred and fifty years later, in 2018, Florida had the highest number of people, over 1.5 million, who had lost their right to vote because of a felony conviction, with more than one in five Black voters unable to access the franchise in Florida because of past convictions, well above their share of the state population and the national average. The state had nearly a quarter of all people in the US kept out of the ballot box because of a felony charge.

The only way for this population to get their rights back was to petition the governor directly, one of just four states still using this practice at the time. Some, like governor Charlie Crist, granted more than 150,000 applications, while others, like Rick Scott, only restored about 3,000 people’s voting rights and imposed a five-to-seven year waiting period before people could apply.

Amendment 4 swept away this history, automatically restoring the rights of those who had carried out their sentences, including parole and probation, with the exception of people convicted of murders and felony sexual offences. And it changed people’s lives.

Evelyn Lugo, 61, of Kissimmee, said she was trapped on the “revolving door” of the criminal justice system for years, after turning to crime to maintain a drug addiction. She just got off probation.

With her previous convictions, finding housing, let alone work, had been a major challenge, given the numerous legal, economic, and cultural barriers facing people with past offences looking to transition into post-incarceration life. Not being able to register to vote added insult to injury.

“It brings you down. You say, well, look at my age, I’m trying to do the right thing, and I can’t even do the right thing and they don’t allow it,” she said. “If you’re a convicted felon, the doors for you are locked. They’re closed.”

Thanks to Amendment 4 and FRRC, she voted for the first time since entering the criminal legal system. Not only did the group help lead the campaign for the amendment, it also paid off the legal fines keeping her from participating in elections, a $1,300 bill she said would have taken her “forever” to clear.

“It felt great,” she said.

Now she helps advocate for rehabilitation services and informs other formerly incarcerated people about restoring their voting rights. These discussions sometimes involve members of the police.

“You’ve probably arrested me before,” she joked, of seeing these officers. “Today I’m out there trying to help others that were like me.”

Neel Sukhatme, a Georgetown University law professor whose organization, Free Our Vote, helped pay off fines and reach out to those in Florida who were eligible to vote again, argues that erecting barriers to voting, housing and jobs for people who have finished their time in the justice system is both morally wrong, and bad public policy.

“Economically, it makes very little sense. You’re not integrating people back into the economy, back into workforce. That should be something that everybody is in favour of, getting people back to being productive and contributing members of society,” he said. “It’s important from a dignitary sense to give people the right to vote after they’ve done their time.”

At its heart, the measure strengthened the US system as a whole, giving more people a chance to participate and have a sense of political agency over the decisions that affect their lives, Mr Meade of FRRC said. It’s the rare thing that transcends politics and should be beloved by everyone.

“It’s a much deeper conversation about democracy and what democracy is really about,” he said.

The conversation would begin taking a sharp turn as soon as Amendment 4 passed.

Under the language of the Amendment, people wouldn’t have their rights restored until they completed all the “terms of their sentence.”

Opponents of the measure seized on this detail, arguing that that should mean the payment of all fines, fees, and restitution attached to a sentence, not just serving jail time. In 2019, Florida Republicans passed a bill called SB 7066, making this interpretation the law.

What to an outsider might seem like a dry change to administrative law was in fact massive blow to the ideals of Amendment 4: because of Florida’s archaic, at times predatory, systems for levying fines against those in the criminal process, the legislation disqualified from voting about 1 million people who still had outstanding balances with the state.

Florida was now locked in an absurd conundrum, what one judge called “an administrative nightmare.” The state, despite keeping people from voting based on their fines, has no central database keeping track of them. The 67 different county clerks offices responsible for such records varied widely, with some keeping detailed electronic records, and others lacking files, paper or otherwise, at all, especially for older convictions.

In some cases, debt collection agencies bought these debts and began pursuing people with odd collections, charging predatory interest rates that meant balances far exceeded the original financial penalty. In other cases, people were accruing fines with interest without them or the state being able to say for sure how much was owed.

And the accumulation of such fines, often $50 to $100 payments which the state uses to fund its courts, have knock-on effects: they can keep people from obtaining a driver’s licence, making paying off the state, let alone finding gainful employment, nearly impossible.

Not surprisingly, this fractured system only led to about 10 per cent of fees ever being paid off.

Taken together, this system was “a huge hurdle for a lot of people” who wanted their rights restored, according to Debbie Cooper, an attorney who volunteered to guide Floridians through a legal services nonprofit called We The Action.

“It’s difficult for people who are trying to restore their voting rights to even figure out what debts they owe. It’s just a long, complicated process and challenging for them to take on on their own, when it’s hard for anybody,” she said. “It seems like they just get stuck and can’t get out from under it. It’s just really sad.”

As a result of these barriers, despite arguments that Amendment 4 might bring the vote back for more than a million people, research suggests only 30,000 or 40,000 people with past felonies registered to vote in the 2020 election.

“What’s the result of this? If you’re a person with a past felony conviction, you are just going to say, ‘It’s better if I don’t vote,’” said Professor Sukhatme. “‘I don’t want to get back in trouble with the law, even though I think I’m ok.’”

Lurking not far beneath all of this are questions of race and power in Florida. No one has forgotten the 2000 presidential election. George W Bush won the contest by 537 votes. And 12,000 people who had been misidentified as being unfit to vote for former felony convictions were struck from the voter rolls ahead of the election, nearly half of them Black voters who would’ve likely gone Democratic.

In 2019, the ACLU, NAACP Legal Defense Fund, and New York University’s Brennan Center sued the state, arguing these fine and fee restrictions violated the US Constitution’s guarantees of equal rights and voting access by creating a de-facto poll tax, which is illegal under the 24th Amendment.

A year later, after an eight-day trial, a district court agreed, finding that the state was barring people from voting based on “amounts that are unknown and cannot be determined.” Florida appealed the ruling, which was upheld at the 11th Circuit, just before the 2020 election.

Supporters of such policies argued they were neutral, or at least didn’t matter much to poor people.

“Florida law applies equally to all eligible former felons, regardless of race, sex, or any other immutable characteristic,” Ron DesSantis’s press secretary Christina Pushaw said in 2020 after the ruling. “SB 7066 was not drafted or implemented with any intent to discriminate. Today’s ruling affirms that.”

“Whitecollar felons, they are going to vote,” argued one former Florida county commissioner at the time, who was disenfranchised after a felony conviction before paying $100,000 in fines. “But people who have lived the drug and gangster lifestyle, they are not rushing out to be able to be part of any system.”

The facts don’t support either argument, according to experts.

According to Professor Sukhatme’s research, recently published in the Vanderbilt Law review with colleagues Alexander Billy and Gaurav Bagwe, Black people represented just under half of registered voters in a sample of 24 counties containing 80 per cent of Florida’s population, but more than two-thirds of those who owe criminal court debt.

These fines and fees “operate exactly as a poll tax would; they augment the monetary cost associated with the act of voting, and, on the margin, reduce an individual’s propensity to vote,” they argue in the paper. “This results in reduced aggregate turnout.”

But they also found something encouraging. Through Free Our Vote, they compiled detailed data on the financial obligations of nearly 500,000 justice-impacted citizens, clearing the debts of thousands and informing tens of thousands with no remaining balance who were free to vote but might not’ve known it.

These interventions boost turnout, by 16 per cent for those with no debt and 26 per cent for those who had their debt cleared.

Thus, it seemed many people, not just those with white collar convictions, wanted to vote if given the chance.

Now, both FRRC and Free Our Vote continued to fundraise to pay off more fines and fees for people looking to restore their rights.

In 2021, Governor DeSantis approved a new clemency process, eliminating Rick Scott’s yearslong waiting periods, though he also signed into law a broad elections bill observers argued will restrict participation from people of colour.

For his part, FRRC’s Desmond Meade says the promise of rights restoration is just as important now as it was in 2018.

“When you talk about true democracy, when you talk about voting rights, it’s a fight to make sure everyone, even if people don’t look like us, if they don’t agree with us, everyone should have a say in how our society is being run,” he said. “I believe that we can create a more vibrant democracy. If ever we find ourselves only advocating for just one group of people, and not advocating for the other half, we’re not talking about democracy.”

So does Free Our Vote’s Neel Sukhatme.

“Progress is never a straight line, he said. “A couple of steps forward, one step back. The recent history in Florida shows that too. People do care about this … People cross the political spectrum. You’ve paid your dues to society. You’ve gone to prison. You’ve spent your money. You’re doing right by the law now, you should have your right to vote back.”

Desmond Meade of FRRC will speak at the upcoming American Workforce and Justice Summit 2022 , a two-day gathering of more than 150 business leaders, policy experts and campaign organizations focused on how corporations can meaningfully engage in justice issues and create change in the workplace and beyond. AWJ 2022, a project of the Responsible Business Initiative for Justice, will take place in Atlanta, Georgia, on 4 and 5 May. The Independent will be reporting from AWJ 2022 as media partner.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments