Fiscal Cliff: It's Biden, McConnell to the Rescue Again

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.In the end, it came down to two 70-year-old men, talking on the phone.

They are not the most powerful men in Washington: Each, in his own way, is a second fiddle. Joseph R. Biden Jr. is vice president. Mitch McConnell, R-Ky., is the Senate minority leader, in charge only of the senators who are not in charge. But these two men — rivals, colleagues and wary friends for almost 28 years — were the ones who finally struck a deal to end the "fiscal cliff" crisis.

The New Year's Eve agreement between Biden and McConnell provided a glimpse at the ways that personality quirks and one-to-one relationships can still change the course of Washington politics. On the Hill's most dramatic night in 16 months, these things seemed to matter far more than raw power.

House Speaker John Boehner, R-Ohio, didn't have enough political muscle to strike a bargain with the president. The president was so intent on showing his muscle that he alienated the Republicans he was supposed to bargain with. Those two, the most powerful Democrat and the most powerful Republican in Washington, tried to strike a historic, sweeping deal, and failed.

Instead, they got what Biden and McConnell could wrangle on the phone at the last minute: a small deal that solved few of the big problems outside the immediate crisis.

Starting Sunday, Biden and McConnell talked repeatedly, hammering out agreements on a complicated array of topics: income tax rates, inheritance taxes, huge budget cuts set to take effect in January. While they talked, the rest of Congress waited. And waited. And complained.

"There are two people in a room deciding incredibly consequential issues for this country, while 99 other United States senators and 435 members of the House of Representatives — elected by their constituencies to come to Washington — are on the sidelines," Sen. John Thune, R-S.D., said on the Senate floor in the afternoon.

Thune was wrong about one thing: In a day of phone conversations, Biden and McConnell were never actually in the same room. But Thune was right that legislators had, essentially, been cut out of the legislative process. By the time a deal was announced, about 8:45 p.m. Monday, there was little time for anything but a vote."At least we would have had an opportunity to debate this, instead of waiting now until the eleventh hour," Thune said.

By now, however, nobody on Capitol Hill should have been surprised at how this would end.

Monday marked the third time in two years that a congressional cliffhanger had ended with a bargain struck by McConnell and Biden. The first time came in late 2010, during a year-end showdown over the expiring Bush-era tax cuts. The second was in August 2011, during the fight over the debt ceiling. In both cases, Washington's new power players — Obama and the tea-party-infused House GOP — couldn't reach an agreement. They were saved by a bargain struck in Washington's oldest tradition, not much changed from the days of Henry Clay except the size of the dollar figures and the presence of a phone.

Two men, both with 20-plus years in the capital, working out the final touches alone.

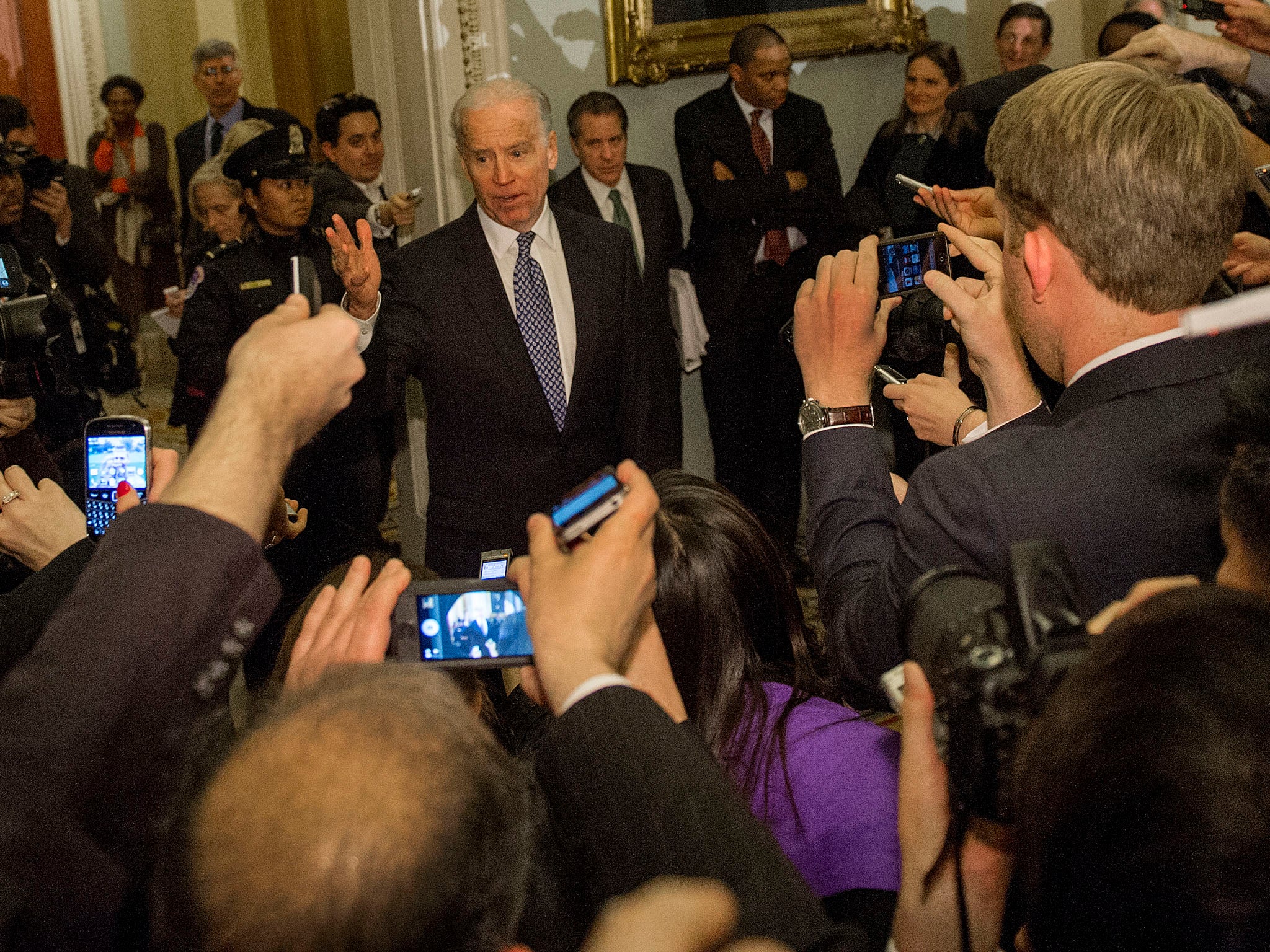

"Happy new year!" Biden said to awaiting reporters, as he swept in to brief Democratic senators on the deal, around 9 p.m. "Don't you enjoy being here New Year's Eve?"

Washington's two unofficial "closers" are remarkably different. The smiling, garrulous Biden has a reputation for empathy: You could spot him as a politician from 40 yards away. McConnell is reserved, deliberate and calculating. He looks like a politician only within the arcane, closed world of the Senate.

But their relationship was built over 24 years spent together in the Senate, where Biden served as a Democrat from Delaware.

"It's not so much a buddy thing," one senior Republican aide said. "The two of them can do business, they can find solutions together."

McConnell, aides say, came to see Biden as somebody who could make decisions fast, and who could cut deals without lecturing his opponents or spiking the ball afterward. Biden, in turn, came to see McConnell as somebody who didn't over-promise. He always knew what his supporters would accept. "Mitch knows how to count better than anyone I have ever known," Biden told an audience in 2011, during a visit to the center named after McConnell at the University of Louisville. The audience laughed. "This is not a joke. When Mitch says, 'Joe, I have 41 votes,' or 'I have 59 votes,' it is the end of the discussion . . . He has never once been wrong in what he's told me."

In this crisis, the two men were called upon when other politicians, far more central to the drama, had faltered.

First, Boehner failed the counting test. Before Christmas, the speaker sought to rally his fractious House behind a "Plan B" to raise taxes only for people making more than $1 million per year. They didn't. Boehner pulled the bill and backed out of negotiations. Then, Washington's top two Democrats — Obama and Senate Majority Leader Harry Reid D-Nev., — proved unwieldy negotiators. Reid seemed to have trouble coming up with a fast counteroffer to a proposal from McConnell. Obama, fresh off reelection, was defiant in public and in private. Even on Monday, as a deal seemed to be drawing closer, Obama gave a televised speech in which he noted that Republicans had already caved on their key demand never to raise tax rates.

To some Republicans, that seemed like a premature and unseemly celebration.

"This is so disappointing. Why wouldn't the president be sitting down with people working out this agreement instead of having a Republican-bashing event?" asked Sen. John McCain, R-Ariz.

For Biden and McConnell, the catch is that — like the two men's previous deals — this agreement doesn't solve Washington's biggest problems related to taxes and spending. The second fiddles had neither the time, nor the power, to do that.

Instead, they scheduled a new crisis in place of the old one, just a few weeks away. It appeared that the fight over budget cuts would be put off for only a few weeks, to coincide with a new showdown over the debt ceiling."This is disgusting, and everybody involved should be embarrassed," said Rep. Steve LaTourette, R-Ohio, as the deal was coming together. The embarrassment, LaTourette said, would stem from the fact "that we're talking about this small-ball — it's not even small ball, it's a Ping-Pong ball — of a proposal. I think it's awful."As he emerged from a Democratic caucus meeting shortly after 11 p.m., Biden spoke briefly with reporters and photographers who awaited him.

"I feel really very, very good about how things are going to go," Biden said. "Having been in the Senate as long as I have, there's two things you shouldn't do: You shouldn't predict how the Senate's going to vote before they vote. You're not going to make a lot of money. And number two, you surely shouldn't predict how the House is going to vote. So I feel very, very good. I think we'll get a very good vote tonight. But happy new year, and I'll see you all maybe tomorrow."

Asked what he said to wavering members of the Democratic caucus, Biden smiled and said: "I said this is Joe Biden and I'm your buddy."

---

Paul Kane contributed to this report.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments