Nebraska cleared to carry out America’s first fentanyl execution, judge says

States, increasingly unable to obtain the drugs needed to carry out lethal injections, are encountering a new wave of opposition

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.A federal judge rejected a drug company's request on Friday to block Nebraska from using its products in an execution next week, clearing the way for the state to carry out its first lethal injection and the country's first execution using the powerful opioid fentanyl.

The drug company quickly moved to appeal the judge's order, leaving uncertain whether the execution will still take place as planned.

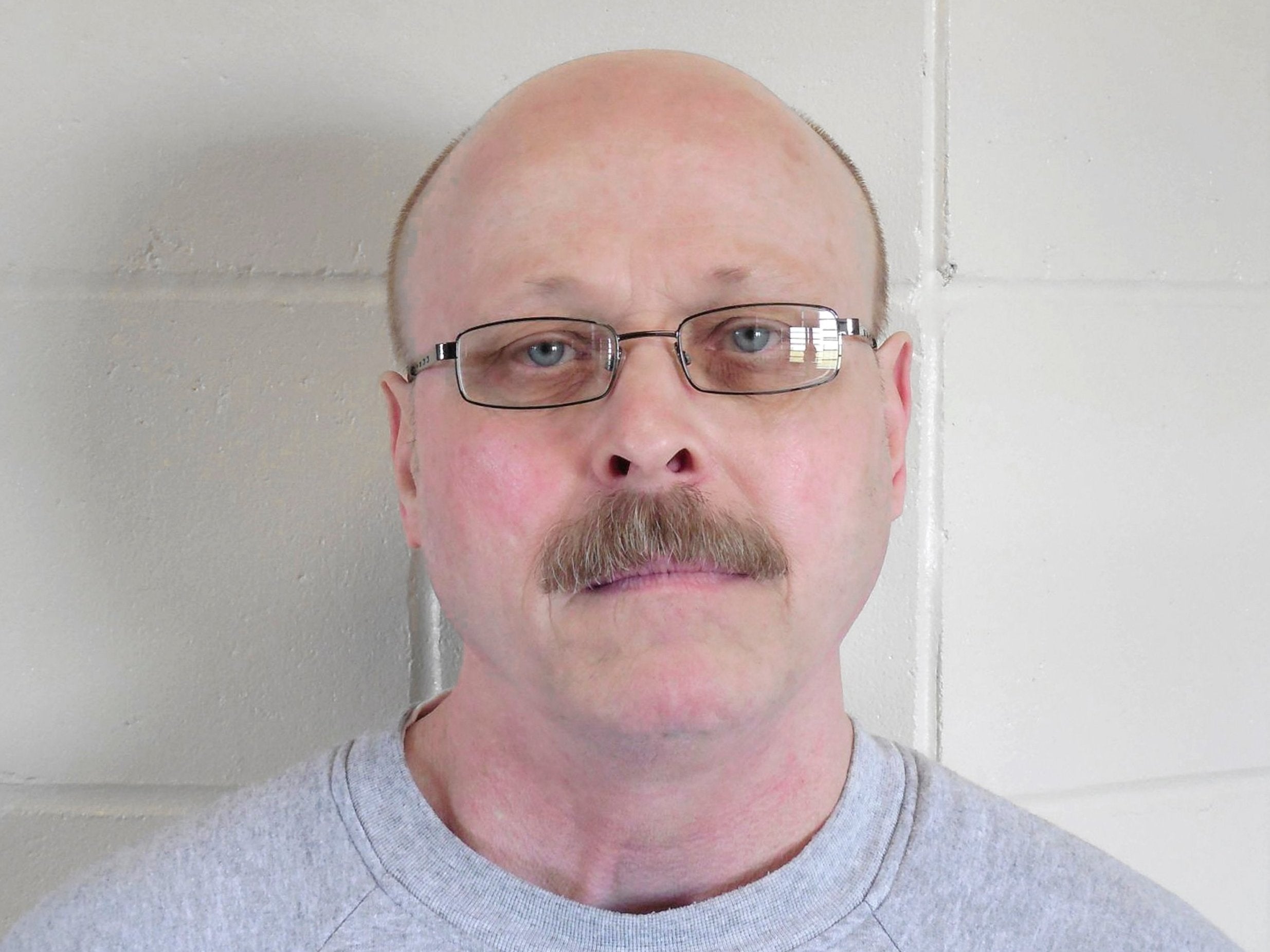

The ruling came in a case centring on Nebraska's plans to execute Carey Dean Moore, a 60-year-old inmate sentenced to death in 1980 for killing two Omaha cabdrivers.

But the case may also reverberate beyond Nebraska, coming at a time when states, increasingly unable to obtain the drugs needed to carry out lethal injections, are encountering a new wave of opposition from the companies that make and distribute those products.

The legal battle over Moore's execution took shape amid Nebraska's efforts to carry out an execution that would be its first in 21 years. During that time, executions and death sentences have both declined nationwide.

Nebraska lawmakers abolished the practice entirely in 2015, overriding a veto from Gov Pete Ricketts – only for voters to reverse that action a year later when it was put on the statewide ballot, an effort pushed by a group given considerable financial backing from Ricketts and his family.

State officials are planning to execute Moore – who has lived more than half his life under sentence of death – on Tuesday in Lincoln, the state capital.

Relatives of the victims in his case – Reuel Van Ness and Maynard Helgeland, both killed in 1979 – have said they are ready to be done with decades of waiting.

Moore has said he does not want to stop his execution or have anyone else stop it for him, though he also belittled state officials who have been unable to execute him for decades as "either lazy or incompetent to do their jobs or both”.

Whether Moore will be executed as planned was thrown into question this week when the drug company Fresenius Kabi filed a federal lawsuit accusing Nebraska of improperly – and possibly illegally – obtaining its products to use in the execution.

In its lawsuit, the company said it restricts the use of certain drugs to try to keep them from being used in lethal injections, a practice that other firms also have in place.

"While Fresenius Kabi takes no position on capital punishment, Fresenius Kabi opposes the use of its products for this purpose and therefore does not sell certain drugs to correctional facilities," the company said in the lawsuit, which was filed in the US District Court for the District of Nebraska.

The company said it sells these restricted drugs to wholesalers and distributors under conditions that are meant to keep the products from being sold to prisons, penitentiaries or jails. According to the lawsuit, though, Fresenius Kabi thinks that it manufactured two of the four drugs Nebraska intends to use next week.

One of the drugs, potassium chloride, is intended to stop Moore's heart. Another drug, cisatracurium besylate, would paralyze his muscles.

The other two drugs Nebraska intends to use are diazepam, a sedative better known as Valium; and fentanyl, the powerful, synthetic painkiller that has helped fuel the country's opioid epidemic and would be used to render Moore unconscious.

The company says its drugs could only have been attained "through improper or illegal means" because of the restrictions they put into place regarding their products, and it asked for the courts to bar Nebraska from using its drugs and to order the state to return them.

The office of Nebraska Attorney General Doug Peterson responded to the lawsuit with a one-sentence statement: "Nebraska's lethal injection drugs were purchased lawfully and pursuant to the State of Nebraska's duty to carry out lawful capital sentences."

In court filings, Mr Peterson's office pushed back against the company's arguments, saying it obtained the drugs from a licensed pharmacy and not through "any fraud, deceit or misrepresentation."

Nebraska officials also pushed back against the company's arguments that it would "suffer great reputational injury" if its drugs are used, saying that only the company's own lawsuit drew attention to its potential involvement.

Mr Peterson's office also argued that they were facing a ticking clock to carry out Moore's execution, saying that the ongoing shortage of available drugs leaves them unable to know when or if they could get more.

"Lethal substances used in a lethal injection execution are difficult, if nearly impossible, to obtain," Scott Frakes, director of Nebraska's Department of Correctional Services, said in an affidavit filed in federal court.

"This problem is not limited solely to Nebraska, but exists in other death penalty states."

States that seek to execute inmates have struggled to find the drugs for lethal injections, a situation fuelled by objections drug companies have to their products being used for capital punishment.

In response, states have turned to a series of new, untested drug combinations. Both Nebraska and Nevada planned to use fentanyl in executions this year in an unprecedented move, while other states have explored different methods entirely.

Oklahoma this year said it would use nitrogen gas for executions, while Utah made the firing squad its backup method of execution in 2015.

Supporters of capital punishment argue that opponents have forced states to pursue inferior options because of what Supreme Court Justice Samuel Alito once called "a guerrilla war against the death penalty”.

Mr Frakes said he contacted at least 40 potential suppliers and half a dozen other states while searching for lethal injection drugs, but only one supplier – which he did not identify beyond calling it "a licensed pharmacy" – was willing to provide them.

That same supplier will not provide more substances, Mr Frakes said, adding that he does not have any backup options for purchasing any additional drugs.

With one of the drugs in question – potassium chloride – expiring at the end of August, Mr Frakes said, any court order blocking Nebraska from using any of the drugs would keep them from being able to execute Moore and essentially change his "final death sentence into a de facto sentence of life in prison”.

On Friday, Richard Kopf, senior US district judge, rebuffed the drug company's request to block Nebraska officials from using the drugs in question.

Mr Kopf said in an order that there was no evidence that the cisatracurium Nebraska will use was manufactured or distributed by the company, nor did he think the company would face any blame or that its reputation would be harmed if it was associated with the execution.

Mr Kopf, who called it "a very strange suit", noted that lawmakers in Nebraska "decided to kill the death penalty, and after that, and very recently, the people decided to resurrect it”.

As such, he explained, the public interest sided with the state officials seeking to carry out Moore's death sentence.

The drug company is "disappointed" in the judge's order, emphasising that its "main purpose is to provide lifesaving medicines to people who care for patients", Matthew Kuhn, a spokesperson, said.

Spokespeople for Nebraska's governor and attorney general did not respond to requests for comment on the ruling and the company's move to appeal. An attorney for Moore declined to comment.

Danielle Conrad, executive director of the American Civil Liberties Union of Nebraska, said in a statement after Mr Kopf's order that the group "commends Fresenius Kabi for taking action to ensure their products were not obtained illegally or used for illicit purposes”.

The case echoed a similar legal action a drug company filed last month in Nevada, which wound up stopping what would have been the country's first execution relying on fentanyl just hours before it was set to take place.

Alvogen, the pharmaceutical firm, accused Nevada officials of "illegitimately" acquiring its drug midazolam, a sedative that has become controversial for its use in executions.

(That drug was used in an execution on Thursday in Tennessee, not long after Supreme Court Justice Sonia Sotomayor said it could inflict "torturous pain”.)

These legal fights have drawn the attention of attorneys general in more than a dozen other states, including active death-penalty states Florida, Texas, Georgia and Alabama.

In a brief filed by Arkansas Attorney General Leslie Rutledge and signed by 13 other attorneys general, they argued that the lawsuit in Nebraska is part of "the latest nationwide campaign being waged by anti-death-penalty activists to deny states access to drugs necessary to carry out lawful executions”. Most of these officials made a similar argument in the Nevada case, which is still pending.

Ms Rutledge highlighted her own experience with a drug firm seeking to block a product from being used in executions.

McKesson, the drug distributor, sought to stop Arkansas last year from using vecuronium bromide it had sold, accusing the state of acquiring it under false pretences.

An Arkansas judge sided with the drug company, but Ms Rutledge appealed to the state Supreme Court, which stayed the judge's order and let authorities use the drug. The state ultimately carried out four executions in eight days.

In a statement, Ms Rutledge accused the pharmaceutical firms of "trying to circumvent the rule of law by using eleventh-hour litigation tactics to stall these lawful executions" and pledged to "continue to fight for justice”.

Washington Post

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments