Exclusive: Anthony Fauci on the Aids crisis, monkeypox, trans rights and his retirement

In an exclusive interview with Io Dodds, Dr Anthony Fauci looks back on his decades-long career in public health

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.“When you suppress something, ultimately it comes out,” says Dr Anthony Fauci. “And it comes out in me, every once in a while, and when I think about it I can barely speak.”

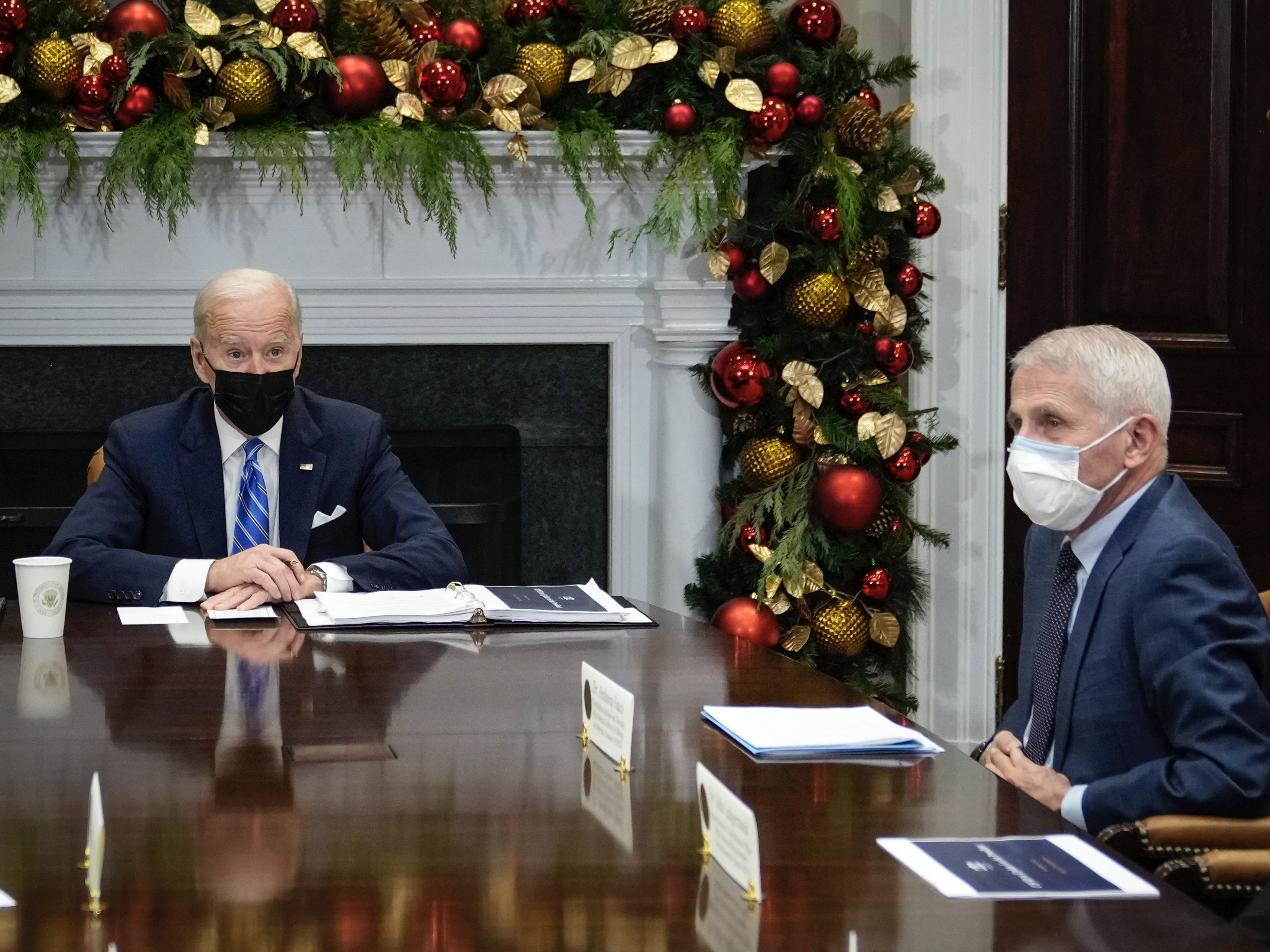

The White House chief medical adviser, who has counselled every US president since Ronald Reagan and led the country’s national infection research institute since 1984, is speaking to The Independent about his experiences during the HIV/Aids pandemic in the Eighties – and the post-traumatic stress disorder that he still lives with today.

“In my career prior to HIV, I had been fortunate enough to develop essentially curative therapies for formerly fatal immune-mediated diseases,” he remembers. “So for about nine years from, 1972 to 1981, I had the feeling of gratification [with] everybody that I took care of. The therapies that I created and developed were saving a lot of lives.

“Then from 1981, for those early years – ’81, ’82, ’83, ’84, ’85 – my entire existence with my colleagues was 12 hours a day taking care of desperately ill young men, and seeing them die no matter what you did for them. Not all of them, but the overwhelming majority of my patients would die. And in order to be able to accept that and continue going, you had to suppress it.”

Today Fauci is best known as the US government’s chief spokesperson on Covid-19, famous for his calm delivery of scientific facts about the virus even while his former boss Donald Trump declared it would “sort of just disappear” and suggested it might be treated by injecting disinfectant.

The 81-year-old New Yorker has been praised as “the Michael Jordan of infectious disease research”, vilified with chants of “lock him up!”, named by a viral online petition as 2020’s sexiest man, and had his face featured on thousands of doughnuts.

Before that, though, he was one of the top US officials responding to the rise of Aids, a lethal and previously incurable autoimmune disease that devastated LGBT+ communities in the developed world before spreading throughout the global population.

Initially attacked by gay activists as an “idiot” and a “murderer”, he chose to heed their concerns and work with them to expand access to experimental drugs and clinical trials, leading firebrand playwright Larry Kramer to declare him “the only true and great hero” of the crisis.

Now, in an exclusive Pride Month interview, he talks to The Independent about homophobia, Ronald Reagan, monkeypox, transgender rights, his own regrets, and his plans for retirement.

How homophobia hobbled America’s Aids policy

“It was looked upon as somebody else’s disease,” Fauci recalls about Aids. “It was predominantly a disease of disenfranchised people – people who were stigmatised already, even before HIV affected the community.”

Today nearly 40 million people live with HIV, the virus that causes Aids. Around 28 million of them are receiving anti-viral medications, which if administered fully and early enough can allow patients to live a long life unimpeded by Aids.

According to the United Nations, about 35 per cent of new infections across the world happen outside the groups that Aids has traditionally afflicted – namely gay and queer men, transgender people, sex workers and their clients, and people who inject drugs. In sub-Saharan Africa, where HIV is now most prevalent, 61 per cent of new infections happen outside those groups.

In 1982, though, one year after Aids was first classified, scientists were still calling it the “gay plague” or “gay cancer”, while a spate of potentially connected deaths among drug users in New York City in the late Seventies had been labelled “junkie pneumonia” or “the dwindles”.

“There was this feeling of intense stigma,” says Fauci. “There was a lot of blame game going on. Things that were egregiously homophobic and egregiously immoral – saying that young men getting infected is the wrath of God punishing you for your lifestyle. There was a lot of that feeling among people, particularly among arch-conservative people, and it took years to break down that barrier.”

That attitude, Fauci says, is “really antithetical to the way we should be approaching public health. When you’re dealing with a disease, it is the virus that is the enemy, not the person who’s afflicted.”

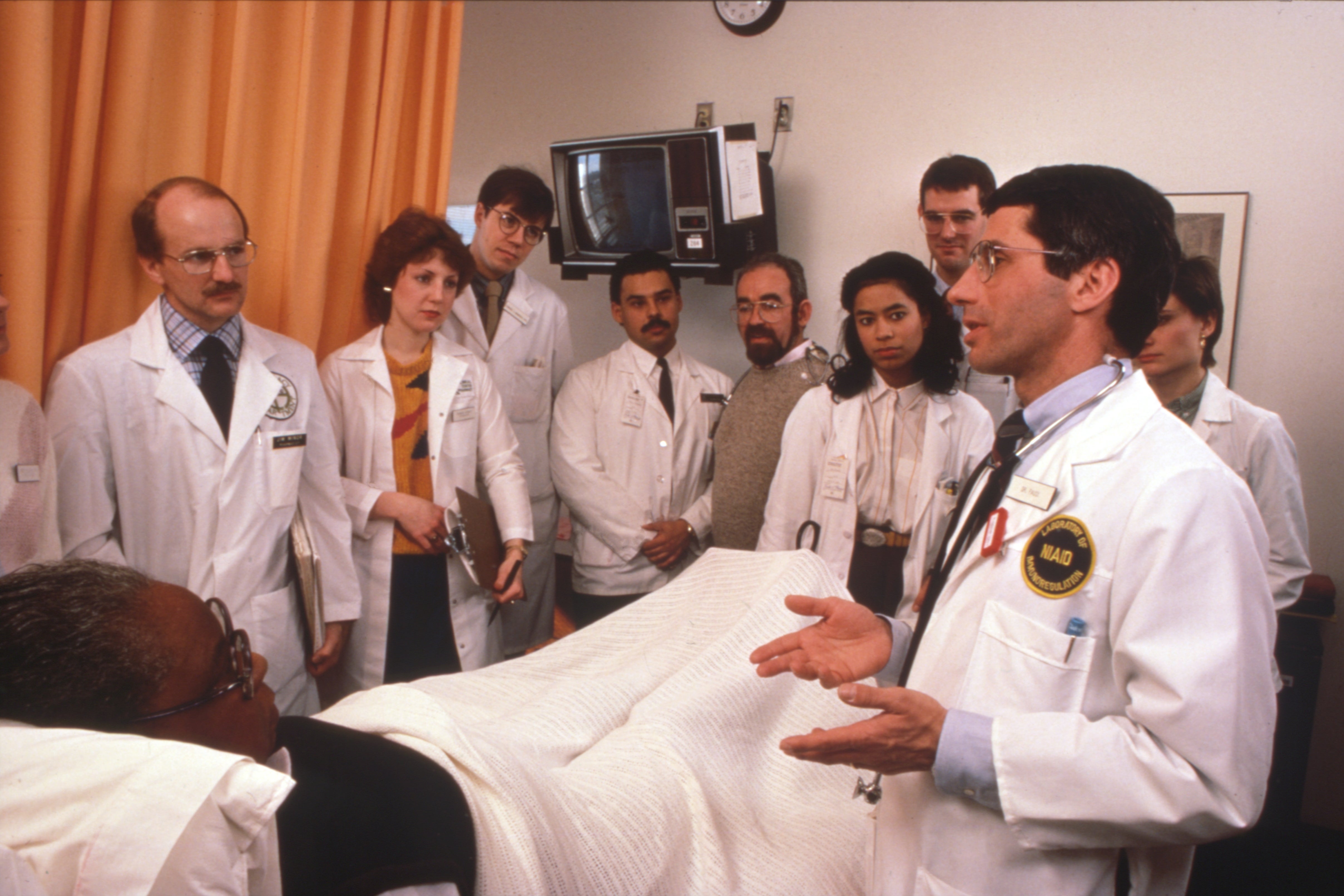

When the pandemic began, Fauci – an Italian-American from Brooklyn who went to a Jesuit high school in Manhattan – had risen to be head of the immuno-regulation lab at the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (NIAID), part of the taxpayer-funded National Institutes of Health (NIH).

In interviews for last year’s National Geographic documentary Fauci, he described how the disease seemed “made for [him]”, given his expertise in immune system disorders, and he made it his top priority despite mentors who told him he was “throwing away a promising career”.

He remembered a day he went walking in Greenwich Village, a New York neighbourhood central to the city’s gay scene, whose residents had kicked off the modern gay rights movement in 1969 by rioting near the Stonewall Inn. It was, Fauci said, an “out-of-body experience”. Everywhere he could see the telltale signs of the little-understood new syndrome, in the faces and behaviour of people all around him.

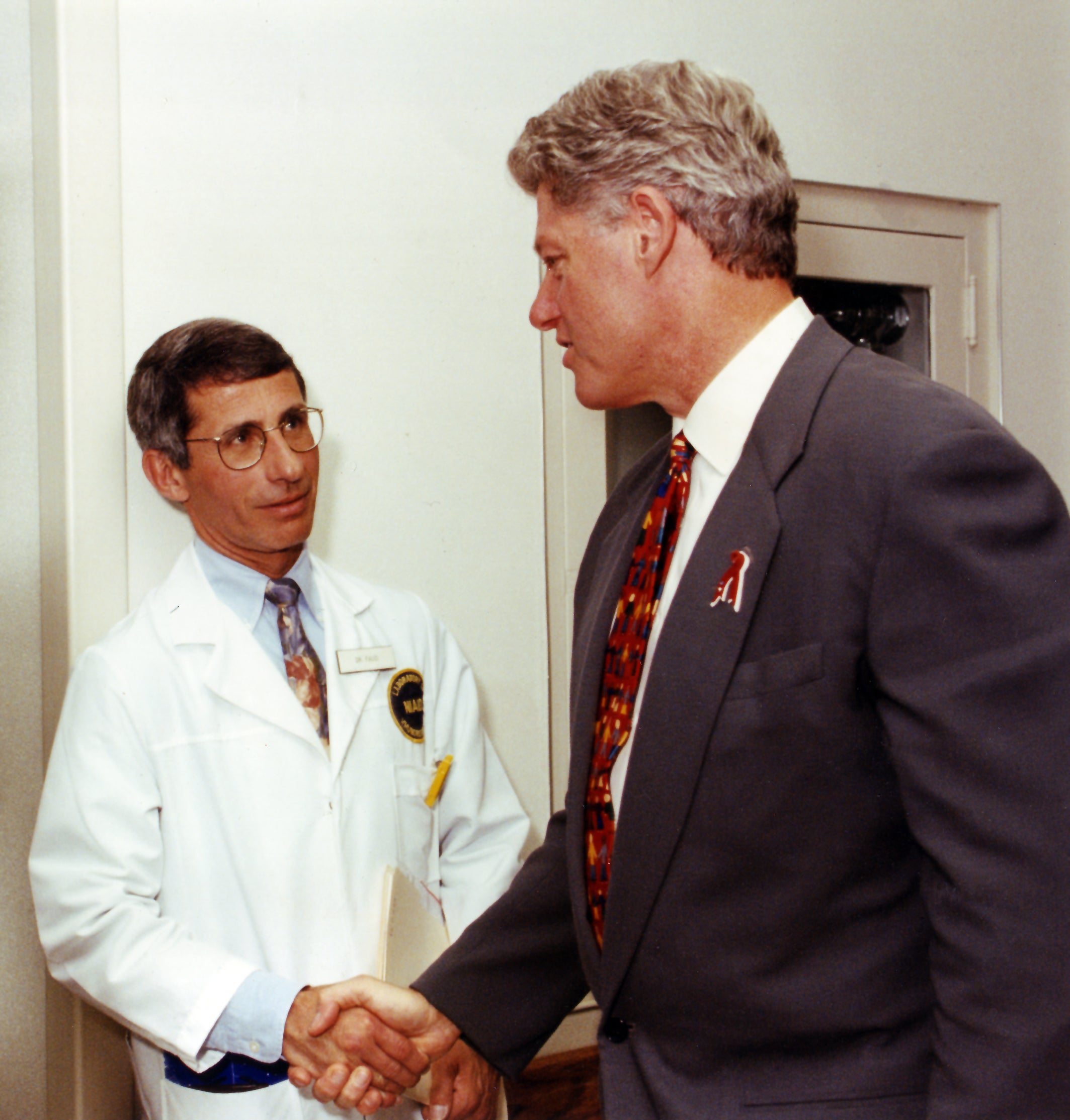

In 1984, at age 43, Fauci was appointed director of NIAID, a position he still holds today. But President Reagan did not consider Aids a priority and his officials were reluctant to talk about it publicly – a reticence, Fauci now admits, in which homophobia played an “important role”.

“Since [Reagan] was a Hollywood megastar, of course he had friends that he knew and probably was very fond of who were gay men,” Fauci tells The Independent. “Yet he represented a very, very conservative administration, and he himself was very conservative.

“The lost opportunity was to use the bully pulpit of the presidency to bring into the open the awareness of this terrible plague that was afflicting a certain subset of our population – shout out the warning about being careful and about putting resources into this.”

Clashing with HIV activists – and seeing the light

As the death toll rose, many HIV activists felt Fauci was missing the boat too.

Throughout the Eighties, the Federal Drug Administration (FDA) still clung to rules that disqualified most Aids patients from participating in clinical trials or accessing experimental treatments. While Fauci’s agency was not responsible for that, he played a leading role in government communications about the crisis and wielded influence within the federal bureaucracy.

“God, I hated him,” Larry Kramer told The New Yorker in 2020. “As far as I was concerned, he was the central focus of evil in the world.” In 1988, Kramer – who had helped found the direct action group Act Up the previous year – wrote an open letter that declared: “Anthony Fauci, you are a murderer. Your refusal to hear the screams of Aids activists early in the crisis resulted in the deaths of thousands of Queers.”

That October, more than a thousand protesters stormed the NIH campus demanding faster research, the inclusion of Aids activists in research committees, and more focus on women and people of colour afflicted by the disease. While Fauci had previously stuck to the traditional attitude that doctors and scientists know best, and should not compromise their rules in response to activism, by then his stance had begun to shift.

He’s still not entirely sure why. “It’s hard to fine-tunedly psychoanalyse yourself,” he says. “But as a person who’s devoted their lives to taking care of people, no matter who they are, what they’re doing, what their status in life is, I felt a great deal of empathy for the situation that these mostly gay young men were going through ... they were suffering and dying at an extraordinarily frightening rate.

“There was a certain degree to which most of the scientific establishment reflexively pulled back from them and shut them out ... so rather than being intimidated by the theatrics and the confrontation, what I did was say, ‘let me put myself in their shoes. What would I do if I were in their shoes, experiencing what they were experiencing?’”

When he actually listened to what they were saying, it made perfect sense to him. “The existing and well-proven scientific approach towards clinical trials and disease, and the regulatory approach, though it had worked well for most of the diseases we were dealing with, it was not appropriately matched to the crisis that these young men, mostly, were going through. You’re talking about a process that’s taking years to do, and they’re looking at their friends and they’re dying in months. So something has gotta change.”

Fauci began a campaign of engagement with Aids activists. While the skirmishes continued, he backed a new “parallel track” scheme that let patients access experimental drugs before they had been approved by the FDA, and while clinical trials were still ongoing. The percentage of the NIH budget devoted to Aids rose to 10 per cent by the early Nineties.

“It didn’t come easily. It wasn’t all over a sudden early night. But over a period of months and then years, gradually, we gained greater respect and confidence in each other,” says Fauci. “Because they were dead on right in most of what they were saying. They weren’t always right... just the way the scientists and the regulatory establishment got things wrong. When we worked together, then we all got it right.”

Fauci still has critics in the LGBT+ community. Sean Strub, an Aids survivor and veteran activist, has accused him of “rewriting history”, arguing that campaigners first asked him in 1987 to back clinical trials for the antibiotic Bactrim – an antibiotic that some Aids doctors were already using off-label as prophylaxis (that is, a preventative medication) and which had already proved itself in trials for other immune-related conditions.

Had Fauci thrown his influence behind Bactrim trials then, Strub wrote, thousands of lives could have been saved.

Asked today if he has any regrets, Fauci says: “Certainly nobody’s perfect, least of all me. Early on, I could have acted a little bit more quickly in some of their suggestions... even though I acted more quickly than anybody else [in government], maybe I could have acted even more quickly and embraced some of their more daring approaches, such as the approach towards prophylaxis.”

Gender transition ‘is real and needs to be accepted’

The Aids pandemic steeled Fauci’s conviction that scientists and doctors must listen to and work with marginalised communities in order to care for them properly.

“Absolutely, that’s the answer,” he says. “Had the world understood that in the very early years of HIV, I think there would have been a lot more information exchanged in a way that is productive, and that could have saved lives ... the lessons we learned from HIV helped us with Covid, and the lessons we learned from HIV are helping us with monkeypox.”

Monkeypox, a viral disease first found among lab monkeys in 1958, and in humans in the Democratic Republic of the Congo in 1970, has recently begun spreading among gay and bisexual men in Britain, the US and beyond, reviving debates about how closely public health officials should tie it to LGBT+ communities.

Unlike Aids, which is deadly without treatment and spreads almost entirely via sexual contact, blood transfusions, and pregnancy, monkeypox is usually mild and can be spread via respiratory droplets and contact with broken skin. Both diseases can affect anyone, gay or straight.

Still, the initial concentration of monkeypox among queer men has led to homophobic commentary that eerily echos the early Aids pandemic.

In response to the outbreak, Fauci says he’s called on his old Aids activist contacts – such as Peter Staley, Mark Harrington, and Gregg Gonsalves – to ask how government agencies should communicate the danger. “How do we alert the LGBTQ community at the same time as not generating or reigniting stigma, which we worked so hard to put aside?” he says.

“That we make sure they know there’s a threat out there – not only the people at risk, but also the physicians that care for them, so that they don’t miss diagnoses and think it’s secondary syphilis or herpes...

“That’s when you embrace the community and ask ’what is the best way to do that?’ Rather than what would happen decades ago, when you had a bunch of people in high places in science and public health and regulation, making decisions about how to engage the community. You engage the community from day one, which is what we’re doing right now.”

It is also an approach he advocates in the treatment of transgender people, who have often historically been dismissed and abused by the medical establishment. Being trans, he says, “is a reality of life. It is real. It’s not something that needs to [be] run away from, it’s not going to go away. And there’s nothing wrong with it. So it needs to be accepted and integrated into the ongoing social order.”

He believes that doctors and scientists today have largely learned the lessons of Aids, and says the last few years have seen “a major step in the right direction – in people understanding the entire concept of a trans person and how we need to integrate that into society and accept it for what it is.”

He adds: “Sometimes when people don’t understand things, they pull away from it. And the more you try and understand, the more you accept. It was sort of the same thing back in the early Eighties ... when you listen, you realise it makes perfect sense. And I think it’s the same thing with acceptance for the totality of the LGBTQ community.”

‘I might retire sooner than most people think’

As for Fauci himself, after being in his post for 37 years (it’ll be 38 this November), does he have any plans to retire?

“You know, to be honest with you, I certainly will some time, and I don’t think it’s going to be a very long time from now,” he says. “But I haven’t really focused on exactly what that would be because we’re sort of in the middle of a public health crisis.”

It will be, he says, when the Covid-19 pandemic is under “better control”, and he’s not sure how long that will take.

“I’m not trying to be evasive,” he concludes. “It might be sooner than most people think, or it might be later than most people think.” But, he says with a laugh, he hasn’t really had a chance to sit down and think about it lately.

The Independent is the official publishing partner of Pride in London 2022 and a proud sponsor of NYC Pride

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments