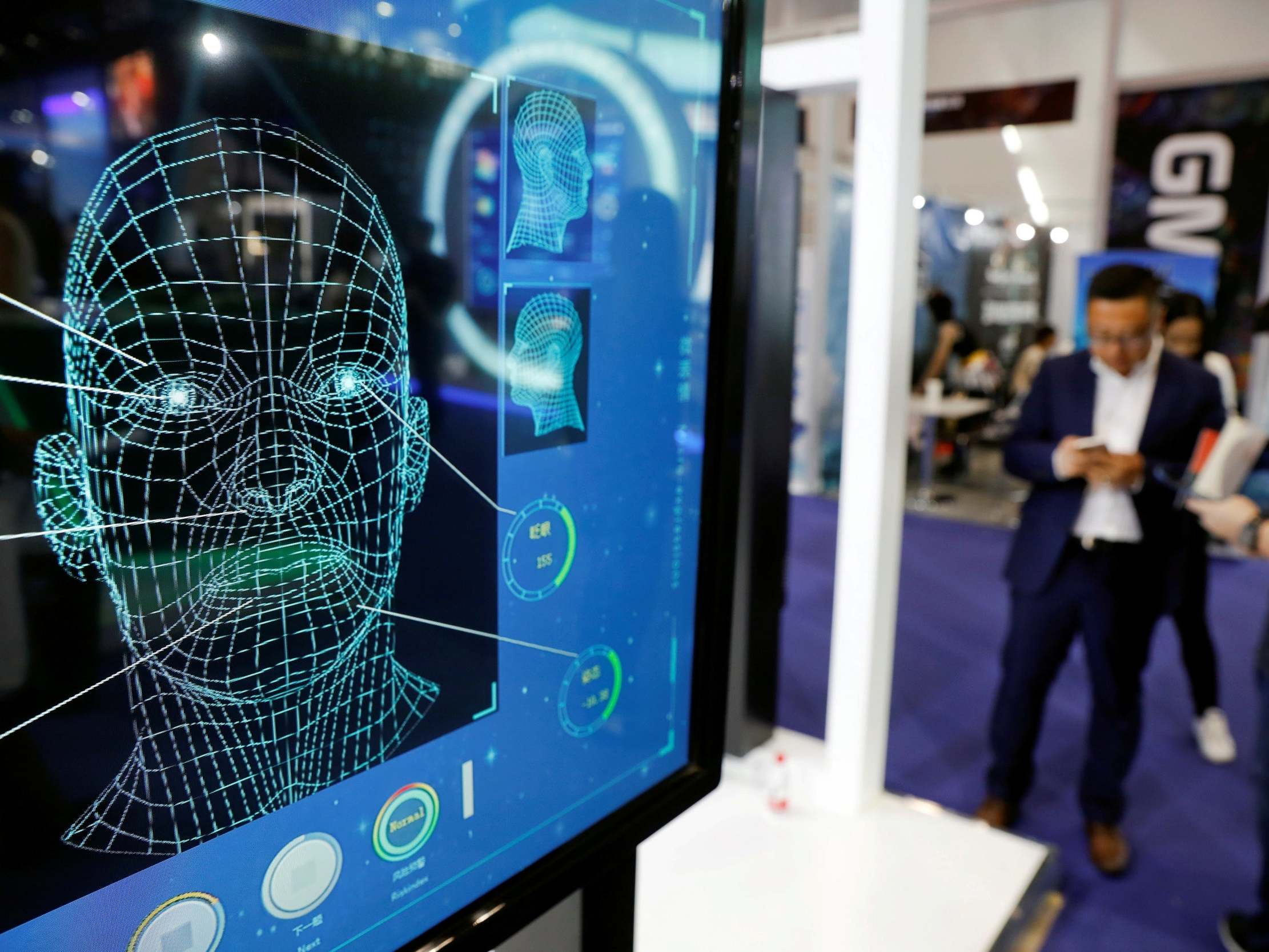

Face masks frustrating facial recognition technology, US agency says

Systems have an error rate of up to 50 per cent when trying to identify masked individuals

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.A new study has found that the masks which protect people from spreading the coronavirus also have a second use, breaking facial recognition algorithms.

Researchers from the National Institute of Standards and Technology have found that the best facial recognition algorithms had significantly higher error rates when trying to identify someone wearing a cloth covering.

The researchers tested one-to-one matching algorithms, where a photo is compared to a different photo of the same person.

This verification method is commonly used to unlock smartphones, or check passports.

It drew digital masks onto the faces in a trove of border crossing photographs, and then compared those photos against another database of unmasked people seeking visas and other immigration benefits.

The agency says it scanned 6.2 million images of about one million people using 89 algorithms supplied by tech firms and academic labs.

While facial recognition methods usually fail to recognise a person less than one percent of the time - three times in every 1000 cases – by wearing a mask that failure rate increases to five times in every 100 cases.

The failure rate can sometimes be raised as high as 20 to 50 percent – as accurate as flipping a coin.

The researchers also found that the more of the nose the mask covers, the lower the algorithm’s accuracy, and that the shape and colour of a mask can have drastic effects.

Rounder masks reduce the rate lower, and masks that are completely black lower the algorithm’s performance more than the surgical blue ones.

“With the arrival of the pandemic, we need to understand how face recognition technology deals with masked faces,” said Mei Ngan, a NIST computer scientist and an author of the report.

“We have begun by focusing on how an algorithm developed before the pandemic might be affected by subjects wearing face masks. Later this summer, we plan to test the accuracy of algorithms that were intentionally developed with masked faces in mind.”

The mask problem is why Apple earlier this year made it easier for iPhone owners to unlock their phones without Face ID. It could also be thwarting attempts by authorities to identify individual people at Black Lives Matter protests and other gatherings.

NIST, which is a part of the Commerce Department, is working with the US Customs and Border Protection and the Department of Homeland Security's science office to study the problem.

It is launching an investigation to better understand how facial recognition performs on covered faces. Its preliminary study examined only those algorithms created before the pandemic, but its next step is to look at how accuracy could improve as commercial providers adapt their technology to an era when so many people are wearing masks.

Some companies, including those that work with law enforcement, have tried to tailor their face-scanning algorithms to focus on people's eyes and eyebrows.

While the researchers tested against one-to-one matching algorithms, they did not test against one-to-many algorithms. These are the variety which are used in public, such as CCTV finding the faces of criminals in a crowd by matching them against a database.

The researchers say that further study will examine the effectiveness of masks against these methods, but it is expected that it will be effective. One-to-many systems have already been shown to have been inaccurate.

Amazon's Rekognition service incorrectly matched criminals to politicians when tested, while in London researchers found a false positive rate of 96 percent when the technology was tested by the Metropolitan Police.

Even before the coronavirus pandemic, some governments had sought technology to recognise people when they tried to conceal their faces.

Face masks had become a hallmark of protesters in Hong Kong, even at peaceful marches, to protect against tear gas and amid fears of retribution if they were publicly identified. The government banned face coverings at all public gatherings last year and warned of a potential six-month jail term for refusing a police officer's order to remove a mask.

Privacy activists, in turn, have looked for creative ways to camouflage themselves. In London, artists opposed to high-tech surveillance have painted their faces with geometric shapes in a way that's designed to scramble face detection systems.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments