Executed in haste, exonerated at leisure

Dakota Indian among victims of mass execution may be pardoned

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.In its fury, America deemed that the civilian courts were too good for these men, who would go instead before a military tribunal, without defence counsel and with relaxed rules for the admissibility of evidence. That one of those condemned would prove later to be innocent was not so surprising.

But this is not about Taliban-trained terror suspects in 2010, but Dakota Indians in 1862, the year when warriors of the tribe, starved of food and money and diminished by the confiscation of their lands, rose up against settlers on the Minnesota frontier. When it was over, they counted among the dead 358 settlers and 77 soldiers.

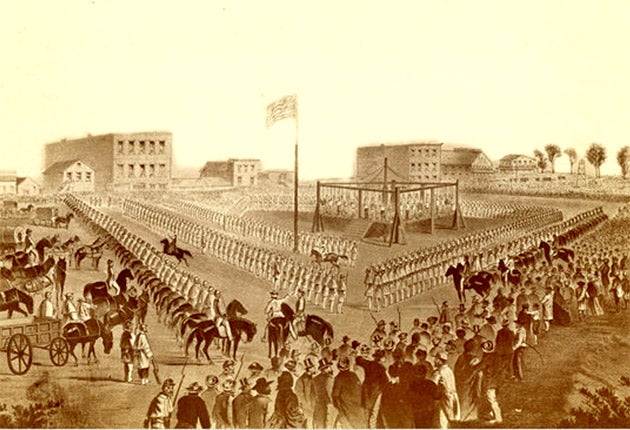

The response was savage, too: on 26 December of that year, 38 Dakota Indians, followers of their leader Little Crow, were led on to a specially built gallows in the town of Mankato and, in front of a surging public hungry for revenge, hanged. It remains the largest mass execution in US history and as its 150th anniversary approaches, some historians and journalists are looking for ways to bring it back to the attention of the American public and of politicians in Washington. They are doing it in part by focusing on the tale of the one innocent man who died on that Boxing Day with all the others.

His name was We-Chank-Wash-ta-don-pee, also known as Chaska, and he was among scores of defendants whose death sentences had been commuted days before by President Abraham Lincoln after the five-man military tribunal had originally designated no fewer than 303 of the Dakota for execution.

In the rush and the melée of "justice" delivered with almost mad haste, he was muddled with another of the detainees and hanged in error. Whether the hanging of Chaska was in fact a simple accident or if more disturbing forces were at play remains a matter of debate. He had been accused of kidnapping a white woman, Sarah Wakefield, and her children and when she later testified that she admired him, rumours spread that the two had become lovers.

Though in its infancy, a campaign is now gathering for a posthumous federal pardon for Chaska. The case was given oxygen by an author and teacher of journalism at Northwestern University, Robert Elder, writing at length about the case and its history in yesterday's New York Times.

"It's time to talk about it and time for people to know about it," said Gwen Westerman, a professor of English at Minnesota State University at Mankato. She is planning to charge her students with doing research to back up the case for a pardon and "put together some more pieces of the puzzle".

Some seedlings of support are already sprouting on Capitol Hill meanwhile. A posthumous pardon for the Dakota Indians would be "a grand gesture and one I think our Congressional delegation should support," said Jim Oberstar, a Minnesota Congressman who lost re-election this year. "A wrong should be righted".

Similar, if somewhat flimsy, encouragement was offered by a spokesman for the junior US senator from Minnesota, the former comedian and author Al Franken. "Senator Franken recognises that this is a tragic period in history. The senator will continue to look into this incident in the next Congress."

Pardons for dead people, even in cases going back more than a century, are not unheard of in America, stirring some to question the validity of such gestures when in the present day, DNA science offers entirely contemporary evidence of the innocent being put on Death Row.

The campaign for a pardon for Chaska will be seen by some as especially important, not just because of the lessons that could be learned from that time, when the Dakota defendants often got hearings lasting less than five minutes.

America, after all, is right now passionately debating the use of tribunals at Guantanamo today. But it is also an opportunity to direct fresh attention to a period of American history – and shame – that remains thinly discussed.

The pardoning of one of the 38 hanged in Mankato would not satisfy many in Dakota who still pause every Boxing Day to commemorate their deaths. But Leonard Wabasha, a local Dakota leader, told the Times that it would at least help to "shine a light". He added: "It would cause people to read and research into it a little deeper. It would be a step in the right direction."

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments