Race-based questioning of Ketanji Brown Jackson ‘mirrors’ experience of Thurgood Marshall

America’s first Black justice was confirmed to the Supreme Court in 1967 but some question how much has changed, writes Andrew Buncombe

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.The aggressive, race-based questioning of Supreme Court nominee Ketanji Brown Jackson mirrored the treatment doled out to the first Black justice Thurgood Marshall more than 50 year ago, a top legal scholar has said.

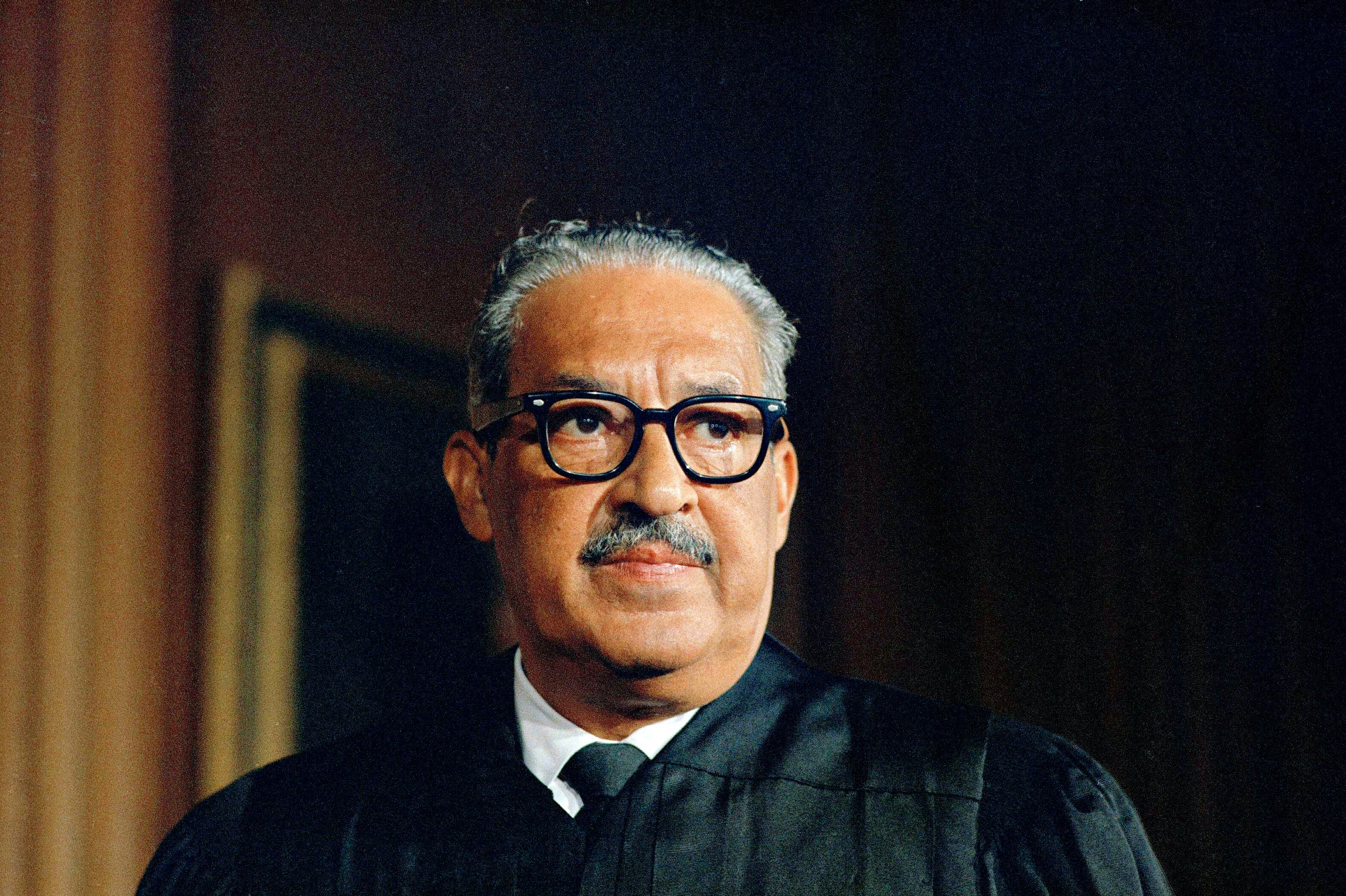

Ahead of this week’s questioning of Jackson by members of the Senate judiciary committee, an event marked by performances by some Republican senators widely condemned for their dishonesty, grand-standing and even rudeness, legal scholar Margaret Russell took a look at the experience of Marshall, who made history in 1967 when Lyndon Johnson nominated him to be the first Black justice on the Supreme Court.

Russell, an associate professor of law at Santa Clara University in California, found the questioning of Marshall, who died in 1993, often focused on questions of crime, a topic that has long been used to try and demonise Black candidates and communities.

One of the senators, John McClellan, a Democrat from Arkansas and an avowed segregationist, said to the nominee: “I know there is a crisis in this country, a crime crisis. And I know the philosophy of the Supreme Court one way or the other on these vital issues is going to be of untold consequences, and has already been in my judgment of serious consequences to the crime situation.”

Another Democratic senator, Sam Ervin, who also opposed desegregation, claimed that Marshall’s experience as a lawyer for the NAACP rendered him unsuitable.

Indeed, as an attorney Marshall had won the landmark 1954 Brown V Board of Education judgment that found racial segregation in public schools was unconstitutional, a decision that Ervin and other many other senators, including Strom Thurmond, denounced.

“It is clearly a disservice to the constitution and the country to appoint a judicial activist to the Supreme Court at any time,” said Ervin.

Senator James Eastland of Mississippi, a white supremacist who chaired the committee, asked of Marshall: “Are you prejudiced against white people in the South?”

The committee eventually voted 11–5 to send the nomination to the full Senate with a favourable recommendation, and Marshall made history when he was confirmedly by the full chamber on August 30, 1967, by a vote of 69–11. A total of 20 senators abstained.

Most experts who watched Ms Jackson being questioned this week assume she too will get a favourable vote out of the committee and will be passed by the narrowest of margins by the senate.

That prospect appeared more likely after West Virginia senator Joe Manchin, about whose support questions had been raised, announced he planned to vote to confirm her.

Yet, many were struck by the nature of the questioning handed out to Jackson, by the likes of Republicans Ted Cruz, Lindsey Graham and Marsha Blackburn.

Cruz, of Texas, alleged that the school in Washington DC, where Jackson is on the board of trustees, supports critical race theory and demanded that she respond to him.

In particular, he raised the issue of a book, Antiracist Baby, which argues that babies are taught to be racist or anti-racist and there is no neutrality. He claimed the book was taught to children aged four to seven at the school in DC.

Jackson said she was not aware of what was taught to students but said CRT was generally not part of the curriculum for children that age.

“I’ve never studied critical race theory, and I’ve never used it. It doesn’t come up in the work that I do as a judge,” she said.

Blackburn of Tennessee also focused on issues of race. She claimed Jackson may have a “hidden agenda’ and claimed she had “made clear that she believed judges must consider critical race theory when deciding criminal defendants”.

She also claimed without evidence that Ms Jackson had “consistently called for greater freedom for hardened criminals”.

She also pointed to a single comment by Ms Jackson in which she praised the 1619 Project, a 2019 collection of essays in the New York Times Magazine that described itself as seeking to reframe the nation’s history by placing the experience of those who were enslaved at the centre of the national conversation.

“You have praised the 1619 Project, which argues the US is a fundamentally racist country, and you have made clear that you believe judges must consider critical race theory when deciding how to sentence criminal defendants,” Blackburn said.

“Is it your personal hidden agenda to incorporate critical race theory into the legal system?”

In her comments to the committee Jackson, said her life had been blessed beyond measure.

“The first of my many blessings is the fact that I was born in this great nation, a little over 50 years ago, in September of 1970,” she said.

“Congress had enacted two Civil Rights Acts in the decade before, and like so many who had experienced lawful racial segregation first-hand, my parents, Johnny and Ellery Brown, left their hometown of Miami, Florida, and moved to Washington DC, to experience new freedom.”

Her loyalty to the nation appeared to be questioned by Graham of South Carolina, who pressed her as to why she had as a public defender represented two of the inmates of Guantanamo Bay.

“After 9/11, there were lawyers who recognised that our nation’s values were under attack, that we couldn’t let the terrorists win by changing who we were, fundamentally,” she said, pointing out that as a federal public defender she does not choose her cases.

“And what that meant was that the people who were being accused by our government of having engaged in actions related to this, under our constitutional scheme were entitled to representation, were entitled to be represented fairly.”

Russell described the questioning of Ms Jackson as “appalling”.

“And I’m actually surprised when people say those politicians are playing to their base,” she says. “I’m surprised that there are people who want them to talk like that.”

She says Marshall had been questioned “very blatantly – can you be fair to white people in the south, and people were much more open and overt about their bigotry”.

She adds: “This week, it’s actually 55 years later, I noticed that I thought it was pretty overt myself in tone.”

She says that Clarence Thomas, the second Black justice to be confirmed in 1991, and whose wife, Virginia is at the centre of controversy over the emergence of text messages she sent to Donald Trump’s chief of staff vowing to support his efforts to overturn the election, did not face such stiff questioning.

She believes this was because Thomas was a conservative who has been nominated by a Republican president and was not seen as a threat to the established order.

Yet, race also played a role in those hearings as they took place amid allegations from a former employee, Anita Hill, who testified he had sexually harassed her while he was her supervisor at the Department of Education. Thomas denied the claims and alleged the way they were being levelled at him amounted to “a high-tech lynching for uppity Blacks”.

Russell says she believes things in the United States have shifted since 1967, with the election of a Black president, a Black vice president and – most likely – its first Black woman Supreme Court justice

“What hasn’t changed, is a very unenlightened approach to the history of racism and slavery at this country’s founding,” she says.

“I mean that, all of us who swear to uphold the constitution – lawyers, lawyers, soldiers, judges, etc – need to remember that the constitution was founded when women and people of colour, and poor people, were not considered in the original meaning.”

She adds: “So, any reference to what the founders meant really has to acknowledge that they were themselves exclusionary and some were slave owners.”

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments