El Salvador: Inside the world's deadliest peacetime country

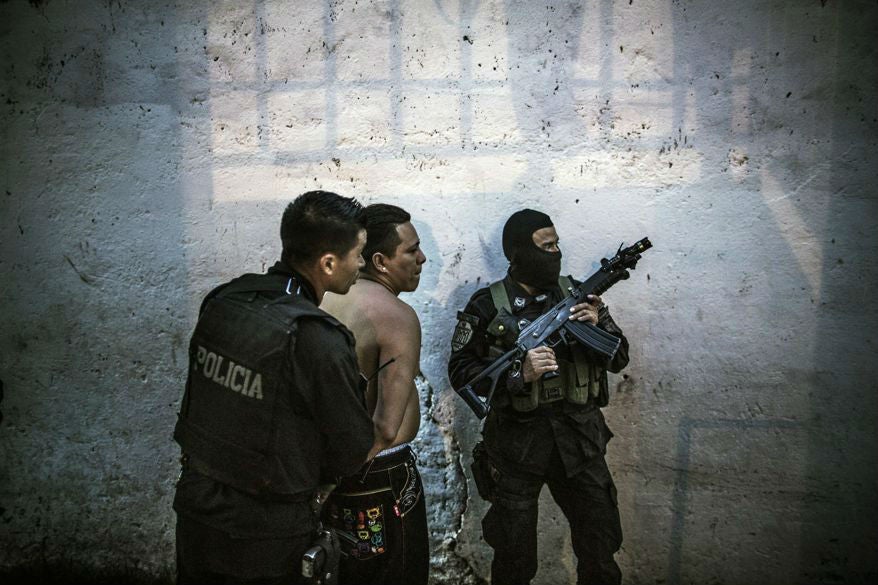

Special report: Extortion, murder and police death squads are pushing people to leave

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

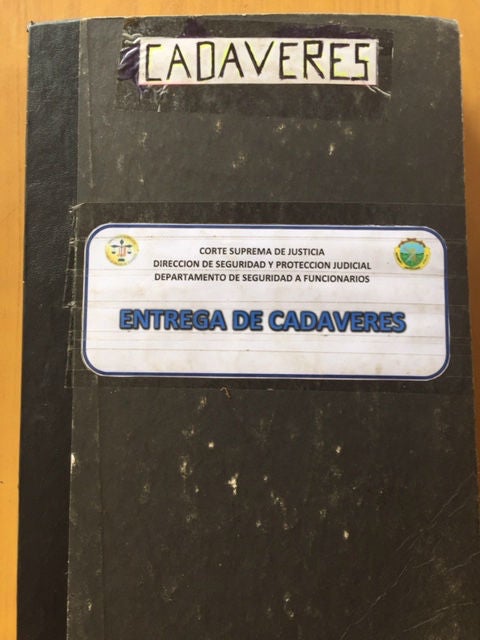

Your support makes all the difference.Throughout the day, and during the night as well, ambulances set off from this building in the centre of San Salvador. They collect bodies, broken and bullet-ridden, from where they have been dumped in the city’s various neighborhoods and bring them to be identified. All the while, families make their way here too, wailing and banging on the gates, desperate for information but not wanting to believe their loved ones are no more.

This is the Institute of Legal Medicine, one of the front lines in a war that few people outside of El Salvador seem to have heard of and which fewer still appear to care about. And yet this conflict, which can trace its roots as well as some of its sustaining causes to the United States, has turned parts of this Central American country of six million people into little less than a war zone.

Violence involving rival gangs that were first established in Los Angeles and are involved in the trafficking of drugs to the US, along with the police and army’s counter-gang operations, has created a devastating situation. Kidnapping and extortion are rife, while the government has been accused of operating death squads. Many, perhaps most, of those being killed are children and teenagers.

In 2015, it recorded 104 murders per 100,000 inhabitants, a rise of 67 per cent on the figures for 2014 and making El Salvador the deadliest nation per capita outside of a war zone. Only nations such as Syria and Iraq are deadlier. By comparison, the UK’s murder rate is 1 per 100,000 inhabitants, while the US, with all its problems of gun violence, has a figure of 4.

“I don’t understand why the outlets in the US, that have lots of resources, have such little interest in the region,” Oscar Martinez, a journalist and the author of A History of Violence: Living and Dying in Central America, said recently. “It’s a region very related to the US because of the subject of migration, because of the subject of violence.”

Ana Ramirez knows all about the violence tearing apart her country. Her 19-year-old son Mario, was shot and killed, apparently in an operation by police and soldiers a few days ago. Now she had come to the “Medicina Legal”, as the mortuary and laboratory is known, to arrange the collection of his body and to rebut the police’s claim that he belonged to a gang.

“His girlfriend called us to say he had been pulled over by the police. By the time I got there they had put his body in the back of a pick-up. They would not let me get any closer,” said the teenager's mother. “I identified him two days ago. He had been shot in the face and his hand. We think he held his hands up to protect himself.”

The dead teenager’s sister-in-law said Mario and other youths had been arrested, and released, a year earlier when the police conducted a raid in the Soyapango township. The police had tipped off the media and a television crew had filmed the whole thing.

“Look,” said Julia Moreno, pulling out her cell phone and showing the video footage. “How can we live like this.”

The footage showed police commandos storming a neighborhood of homes made by metal sheeting and breeze blocks, forcing their way into the buildings and detaining half-a dozen residents. Moreno, who has a child, said she and husband were desperate to leave the country. They simply no longer felt safe.

“We’re living in a war,” she said, tears streaming down her face. “To have a young relative is a crime.”

The figures compiled by the teams of doctors, mortuary officials and government officials, is nothing less than startling. Between 1 January to 18 May, they recorded 2,555 violent deaths, of which a handful were suicides and road traffic deaths. Of these around 90 per cent were men, and in 80 per cent of cases the cause of death was shooting. Around 22 per cent of those killed were aged between 15-19 with another 20 per cent between 20-24.

An official, who asked not to be identified, said the institute had eight white Toyota Hiace vans which served as ambulances. Whenever the institute received a call that a body had been found, a driver would set off with a doctor and medical assistant. Depending on the area in which the body had been found, the team would be accompanied by one or more police units.

The staff use whatever is found on the body to try and identify it. Those bodies that cannot so easily be identified are photographed and the image posted on a noticeboard where family members can come and check.

The institute, partly as a means of protecting itself, makes no assessment as to whether a person has died as a result of gang violence. “Our job is to identify the body and determine the cause of death,” said the official. “We focus on the scientific side of things. The investigation is done by the legal department and the police.”

Estimates suggest there are up to 70,000 active gang members in El Salvador, most of them aligned to two main outfits – Mara Salvatrucha, or MS-13 and Calle 18. The gangs were originally established in Los Angeles, in its extensive prison system.

During the 1990s, many of the gang members were deported to El Salvador, which was then recovering from a civil war that had left as many as 75,000 people dead, and most of them set free. Since then, they have established strongholds throughout the country and are involved in extortion, people trafficking, the drugs trade, robbery and prostitution.

In 2012, the US, which during the civil war had armed and supported the military government, designated MS-13 as a “transnational criminal organisation” and sought to seize its assets.

“This action positions us to target the associates and financial networks supporting MS-13, and gives law enforcement an additional tool in its efforts to disrupt MS-13’s activities,” said the US Treasury Department.

In El Salvador, the gangs had devastated normal life, so much so that their activities are now acting as one of the main factors pushing people to try and leave the country.

A survey of Salvadoran migrants published earlier this year by the Technological University of San Salvador found that 42 per cent left their homes because of violence. In 2013, the percentage citing such a reason was just five per cent.

Each weekday mornings, long lines stretch outside the US Embassy in San Salvador with people seeking a visa. More people try and reach there illegally, and every day buses drop off people without the proper papers who have been caught trying to enter Mexico and head north.

Maria Evelia was waiting outside the compound while her 21-year-old son, Luis, collected a visa to allow him to join his father in Houston. She was sad to see him leave, she said, but happy he was getting away from a place where young people were so vulnerable to the influence of gangs. “This is the perfect age for the gang members to recruit,” she said of her son’s age.

Once the bodies are identified by the families who come to the Medicina Legal, they are collected by funeral businesses who arrange burial. Rafael Neda never wanted to work as an undertaker, but he needed a job and in El Salvador there were plenty of bodies to bury. More of the people he buried, he said, had suffered violent deaths than natural ones.

On a recent morning he was waiting outside the institute with a Nissan truck, in the back of which was a coffin. He said he was there to collect one of three teenagers who had been kidnapped by gang members, held for three days and then killed.

Neda described a situation in which people with no associations with gangs but living in a certain area could imperil their lives, simply by entering a neighborhood controlled by different criminals. Often people were taken as spies, or government informers, said Neda, who claimed he was held at gun-point three weeks ago while collecting a body. “The hardest part for me is when we have to take the bodies of children. There was a three-year-old who had been hit by four bullets. He was with his uncle.”

The government’s efforts to counter the gangs has gone in fits and starts. Earlier this year, rival gang members held a press conference at which they said they were willing to enact a ceasefire that had been negotiated by the previous government and ran from 2012-2014, if the authorities in turn stopped their operations after them.

Since then, in a twist that suggests a political hand, reports suggest that a number of officials involved in ceasefire have themselves been detained. President Sanchez Ceren, a 71-year-old former communist guerrilla, has taken a tough line on crime, deploying a 1,000-strong unit of soldiers and police commandos to take on the gangs. People in some neighbourhoods say the units have been given a “green light” and the government units have frequently been accused of extrajudicial executions and of acting with impunity.

The government’s own human rights prosecutor, David Morales, investigated two incidents last year and conluded “there is serious evidence that government agents acted outside the law”.

Director General of the Civil Police, Howard Cotto, said in an interview that any such incidents were investigated by other officers and cases brought against those found guilty. Formerly part of the left wing rebels who 20 years ago fought against the military-run government, said he had long fought for human rights.

He said the biggest challenge in taking on the gangs was to strengthen public control of areas where they were active, and the nation had to develop a social development plan, alongside any policing actions. “The strategy of the gangs is based on the lack of organising within the community,” he said.

Yet, such solutions do not appear close. Another family that recently made its way to the Medicina Legal was in search of information about a man called Hector Antonio, who had been shot and killed in the town of San Luis Palpa, about 25 miles to the south-east.

His sister, Santos Cruz, again insisted her relative had nothing to do with the gangs, and yet he had been shot and killed two days before. “A group of men came to our house. They were wearing police uniforms,” she said. “They were dressed like police but they had no badges.”

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments