Dr Seuss and the tale of ‘cancel culture’: How a liberal Twitter term became weaponised by the right

Right-wing pundits claimed ‘childhood is cancelled’ after publisher withdrew several Dr Seuss books for racist imagery this week. But is the backlash just the latest distraction technique?

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.It’s been a busy week for ‘cancel culture’.

Republican representative Jim Jordan called on the GOP to hold a committee hearing into the “dangerous phenomenon” that was “a serious threat to fundamental free speech rights”; Nobel Prize winning author Kazuo Ishiguro warned that it created a “climate of fear” amongst writers; and some children’s books got removed for depictions of racist imagery.

Unsurprisingly, the last one caused the biggest backlash, with right-wing pundits claiming that ‘childhood is cancelled’ after the estate of Dr Seuss quietly removed six lesser read books which they said featured “hurtful and wrong” racial stereotypes, first published in 1937.

Author Theodor Geisel’s more famous works, like Green Eggs and Ham, which sold more than 338,000 copies in the US last year, and Oh, The Places you’ll Go!, which sold 513,000, remain untouched.

Many welcomed the move, claiming it was high-time that problematic, classic children’s literature, often written nearly a century ago, be reassessed.

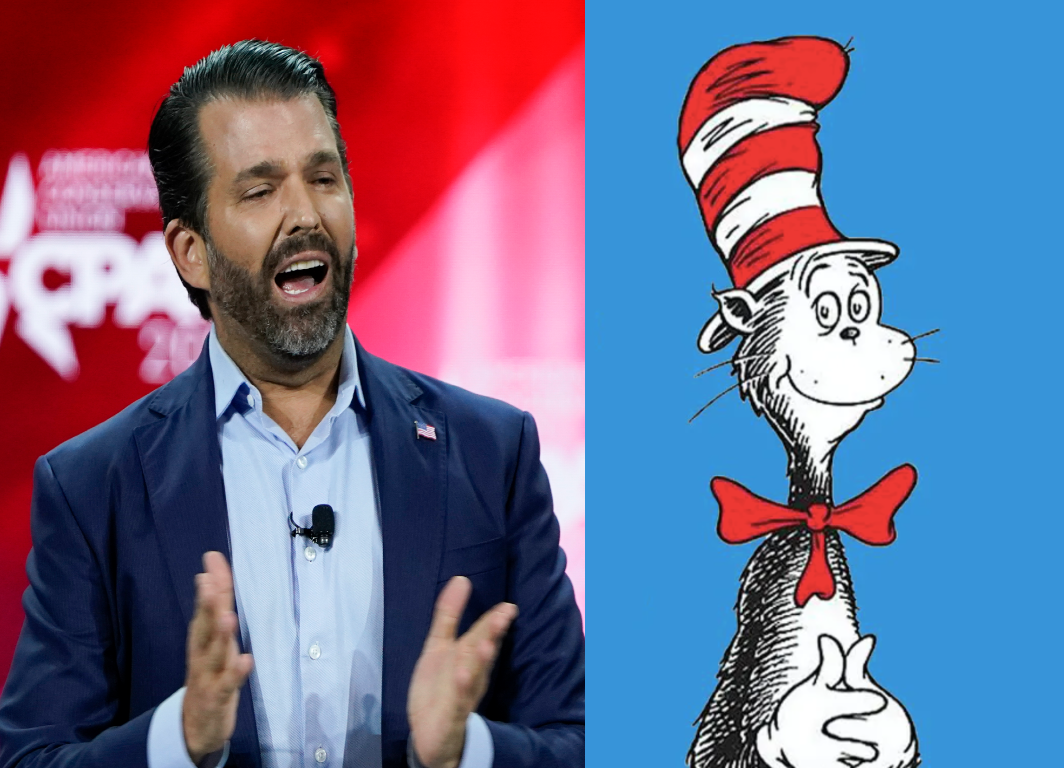

But some conservative figures like Donald Trump Jr and Fox News have eagerly seized on it, and other recent incidents like the changing of the name of Mr Potato Head, as their latest ‘grinch’; stoking the fires of anger and fear by claiming it’s “fascism” and that childhood itself has fallen victim to so-called ‘cancel culture‘.

This new buzzword, alongside “woke mob”, has come to symbolise anything from social media backlashes and boycotting of commercial brands and celebrities, to online pile-ons of average citizens that cause them to lose their jobs or dignity, to digging up old social media posts and re-examining what is acceptable language.

But it also seems to have replaced “fake news” in the Conservative lexicon when it comes to stirring up hatred of the media and faux hysteria over the demise of ‘traditional values’, religious beliefs and freedom of speech.

It was the theme of last week’s Conservative Political Action Conference (CPAC), titled “America Uncancelled”, which ironically hadn’t even begun before it un-invited a guest speaker who had allegedly expressed antisemitic views.

In other words, their appearance at America Uncancelled had been cancelled.

This latest diversion tactic, also known as the ‘dead cat strategy’, is a weapon of mass distraction.

Public shaming, or ‘mob justice’, is not a new concept. The earliest recorded use in English of a pillory, or stock, in which disgraced citizens would have their hands and head locked in public spaces, was 1274. Even the Romans used crucifixion to add a layer of public and psychological humiliation to the death penalty.

Despite legal, public embarrassment being phased out around 1837 in the UK and 1839 in the US, there are multiple judges still practising it today.

Like Ohio Municipal Court Judge Pinkey Carr, who in 2012 reportedly ordered Shena Hardin, who was caught on camera driving on a pavement to avoid a school bus, to stand at a cross-road and wear a sign that read: “Only an idiot would drive on the sidewalk to avoid a school bus.”

Etymologically the word ‘cancelled’ can be traced back to the Latin ‘carcer’, meaning ‘prison’.

Its modern use may have first popped up in mainstream, popular culture in the 1991 cult movie, New Jack City, starring Wesley Snipes as crime boss Nino Brown, as spotted by Vox in 2019.

When his girlfriend complains about the murders he has carried out, Brown slams her onto the table, drips Champagne on her, and says: “Cancel that b***h. I’ll buy another one”. It was a line later referenced in lyrics by rappers like 50 Cent.

But, unlike phrases like ‘MeToo’, ‘cancel culture’ can’t be traced to a single individual, but has evolved over time on social media from colloquial use by African Americans, to a symbol of the 21st century phenomenon of online bashing, to a rallying cry by conservative politicians.

In 2014, when TV critic and assistant professor at Old Dominion University, Miles McNutt, became one of the first people to use the phrase “cancel culture” on Twitter, he was actually referring to TV shows and “the metrics by which a TV series’ success is measured and the speculation over which shows will survive”.

So, the cancellation of actual culture, not a culture of cancellations.

He told The Independent via email that he was “absolutely baffled (and remain baffled)” by any association with the phrase as it is used now.

It began to grow in popularity from around 2016, notably with Black Twitter users, when it started to become identified with boycotts, before exploding into mainstream use around 2019, according to Google Trends.

In 2017, Shanita Hubbard, journalism professor and author of the upcoming book, Miseducation: A Woman’s Guide to Hip-Hop, published by Hachette in 2022, used the phrase on Twitter to discuss criticism of the African American Olympic gymnast, Gabby Douglas, who had apologised for comments she made in the wake of her industry’s sexual abuse scandal.

Hubbard wrote: “Let’s talk ‘cancel culture.’ Personally, I am willing to give a lot of grace to young Black girls simply because the world doesn’t. I wasn’t born reading bell hooks. I had to grow. So does Gabby Douglas. And so do some of you.”

She added: “Giving room to grow, change and improve is not a pass.”

Ms Hubbard told The Independent that she believed the architects behind the current use of ‘cancel culture’ in the political sphere are powerful, white conservatives who were using it as a distraction technique.

The writer said: “It’s almost exhausting to have this conversation about this mythical cancel culture. It’s a very fictitious thing. It’s a weapon that a lot of powerful, privileged people use as a shield to avoid accountability.”

The ‘dead cat’ strategy was popularised under that name by the famed Australian strategist Lynton Crosby (once called “the manipulator with the Midas touch” and “the Wizard of Oz”, quietly working behind the curtain whilst your eyes are fixed elsewhere) who delivered now prime minister Boris Johnson’s mayoral wins in London in 2008 and 2012, as well as the UK’s surprise 2015 win for the Conservatives, setting up the Brexit showdown a year later.

The premise is simple: If you don’t like the narrative or are losing an argument, throw a ‘dead cat’, or otherwise shocking statement or bit of news, on the table, and all talk on the former topic will end.

Revealing Mr Crosby’s tactics that he would later use during the ill-fated EU Referendum campaign and his somewhat disastrous premiership in the UK during the pandemic, Mr Johnson wrote in 2013: “Everyone will shout ‘Jeez, mate, there’s a dead cat on the table!’; in other words they will be talking about the dead cat, the thing you want them to talk about, and they will not be talking about the issue that has been causing you so much grief.”

It’s a technique used to great effect by former president, Donald Trump, and other conservatives, from Hilary’s emails in 2016, to “fake news”, to the “stolen” election in 2020.

Mr Trump himself compared cancel culture to totalitarianism in 2020, whilst calling for multiple reporters and politicians to be fired.

Ms Hubbard told The Independent that it works well for powerful, mostly white, conservatives as a left-wing bogeyman they can rail against publicly, while knowing that they themselves cannot be cancelled.

Like spreading fear about a virus to which you know you are immune.

“The truth of the matter is [cancelling] usually only harms marginalised, ordinary people, a lot of black people.” she said.

“It’s deeply painful to see time and time again people who look like you never getting allowed to grow or make mistakes, and others, very powerful, privileged people, never being held accountable. That is how you know cancel culture is invented. We live in a twilight zone where people are yelling ‘cancel culture ruined my life’. When in reality there is nothing that powerful politicians and police officers can do to get cancelled.”

One of the earliest examples of that would be Colin Kaepernick, the NFL player who started to take a knee during the National Anthem in 2016 to protest racism and police brutality. The practise is now wide-spread, especially following the global rise of the Black Lives Matter movement last year, but he still cannot find a job, five years later.

And in contrast, in the year since the killing of black medical worker, Breonna Taylor, 26, who was shot while in bed during a botched police raid on her home, no police officer has been charged in connection with her death.

Or the cancellation of the career of the Grammy award-winning, black gospel singer Chrisette Michelle for singing at Mr Trump’s inauguration in 2017.

Compared to the election of Brett Kavanaugh to the Supreme Court despite multiple sexual assault allegations in 2018.

Ms Hubbard makes a distinction between internet pushbacks or accountability exacerbated in intensity by access to social media for millions of people at a time, and a mythical, out-of-control lynch mob that is coming for you and will destabilise western democracy.

“The question is: are you a victim of cancel culture or are you being held accountable for your behaviour?”, she said.

“When you shoot out a tweet you are showing your unedited self. And a lot of these politicians and conservative figures who usually sit in a TV studio and don’t hear from the general public are not used to immediate feedback. It’s shocking them. People hold no bars on social media.”

It’s not all negative though.

She notes that some pushbacks last year, like the controversy over white people posting black squares on social media to show support for the Black Lives Matter movement, yielded positive results, because it focused on practical feedback for a mass group, rather than hammering an individual.

“It was a really meaningless gesture … and people were told, if you want to actually show support and allyship you can donate to groups, attend a protest. People with large social media followings, like [actor] Leslie Jordan, offered up their platform to black activists. I saw people start to pivot. I thought that was fantastic.”

The phrase cancel culture isn’t going away any time soon, nor is the vogue for public shaming, or the weaponizing of perceived ‘threats’.

In the wake of the Capitol riot in January that left five people dead, Missouri senator Josh Hawley, was accused of encouraging the crowd of far-right protestors by saluting them with a closed fist.

The 41-year-old lost his publishing contract for a new book, angrily decrying the move as “Orwellian” and vowing to “fight this cancel culture with everything I have.”

He found a new publisher just days later.

And yet Mr Hawley took to the stand at CPAC last week to declare to a jubilant crowd: “Didn’t anybody tell you? You’re supposed to be cancelled!”

As The Washington Post warned back in 2017: “We gape at dead cats, but the wolf is at the door.”

There will always be another ‘Dr Seuss’.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments