The race to spare Julius Jones from the death chamber

Julius Jones has been fighting to leave Oklahoma’s death row for 20 years, sentenced to die for a crime he—and a growing body of evidence—says he didn’t commit. Josh Marcus writes

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.The 1999 murder of Paul Howell was senseless and sensational. The killing, in front of his two young daughters, devastated his family and stunned the surrounding community. Hundreds of officers and heavily armed SWAT troops fanned out across the Oklahoma City suburbs, searching for two Black teenagers accused of killing the prosperous white businessman during a carjacking.

Once police caught a suspect, 19-year-old Julius Jones, the state’s most prominent prosecutor and newspaper editorial board both called for the death penalty in a manner of days, well before all the facts had been established.

Following a front page trial the year later, they got their wish. Jones was sentenced to death. The system carried out justice as it was then conceived. The sentence was swift, and the most severe imaginable.

But despite the spotlight on the case, there’s another side to this story that has only recently come to light. Julius Jones has always insisted that he is innocent, the victim of a frantic police investigation and a perfect storm of prosecutorial vengeance. Starting from the moment he was arrested, he has never been able to stand up in court and share his full side of the story—not during his fevered trial, not during decades of fruitless appeals that followed. He has remained on Oklahoma’s death row for over 20 years, a man alive but largely consigned to the silence of the grave. Until now.

After years of work by family, local activists, public defenders, and, more recently, Hollywood heavyweights like the actress Viola Davis and reality star Kim Kardashian West, Jones has one last shot at the justice he says is 20 years delayed. His legal appeals have been exhausted. On 26 October, Jones, now 41 years old, having spent more time living on death row than off it, went before Oklahoma officials to argue for his life during a clemency hearing. If Oklahoma governor Kevin Stitt is ultimately moved by what he hears, Jones could be taken off death row and given a life sentence instead, opening up the possibility of parole and eventually walking free. If Mr Stitt is not convinced, Jones’ execution date is set for 18 November.

Jones was sent to death during the height of the “Tough on Crime” era. His fate begs the question: after years of civil rights activism, how much has the criminal justice system, and America at large, really changed?

Boy Scouts and ‘superpredators’

Paul Howell, a 45-year-old insurance executive, was shot and killed in his parents’ driveway on 28 July, 1999. His sister, Megan Tobey, was the only eye witness. She said the shooter was a young Black man wearing a red bandana over his face, who had a few inches of hair peeking out from under a skull cap.

Even by the standards of the time, an era that birthed the ludicrous “superpredator” stereotype of murderous Black teens, Julius Jones would seem an unlikely candidate as the face concealed underneath that mask.

(The Howell family did not respond to multiple requests for comment.)

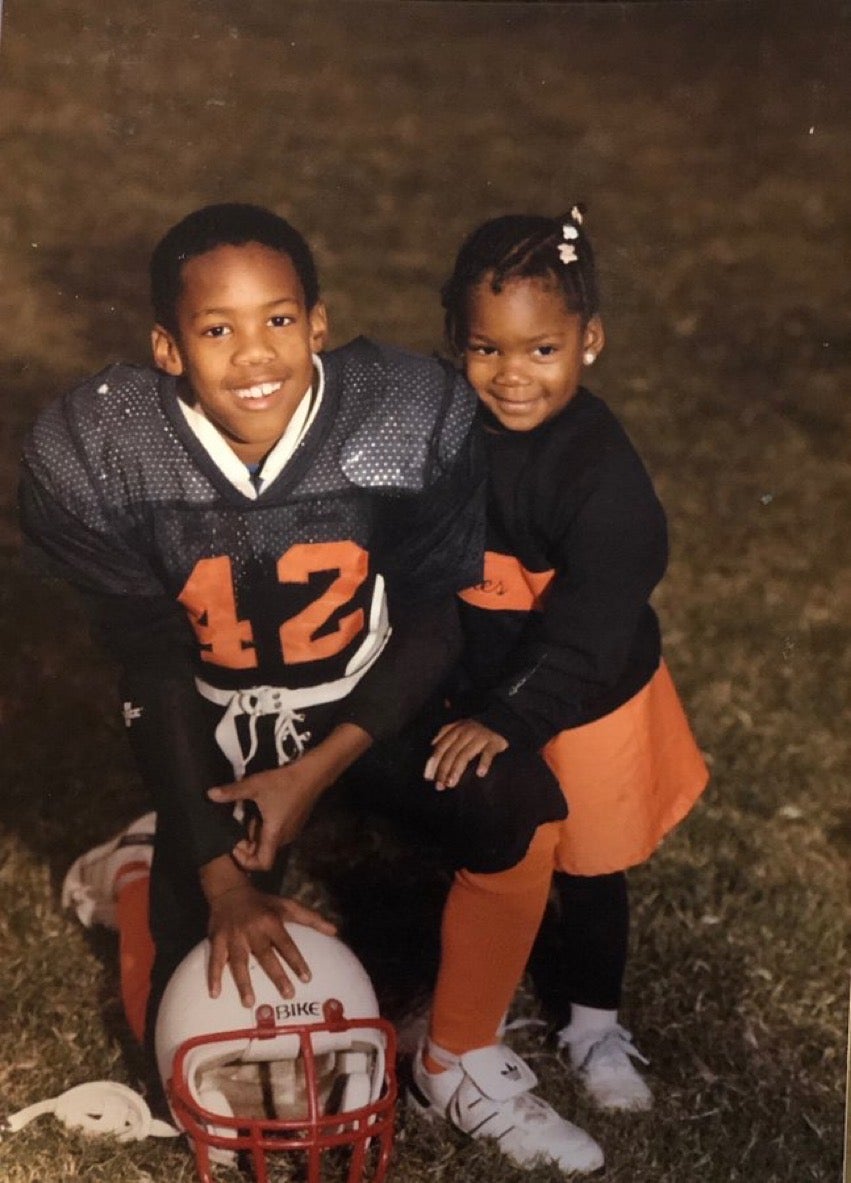

“Sometimes I think of him being a little Boy Scout or something,” Madeline Davis-Jones, Julius’s mother, told The Independent. Julius was active in church, in sports, in helping kids around the neighbourhood with their homework. “He liked helping people, I guess that’s one of his problems.”

His younger sister, Antoinette Jones, remembered fondly how Julius once took her to a fair where he promised to let her go hang out with her friends, only to notice him secretly trailing after her from a distance to make sure she was safe.

Julius was one of only two Black males to graduate in the top 10 percent of his class at Oklahoma City’s John Marshall High School. At the time of the Paul Howell murder, he was at the University of Oklahoma on an academic scholarship.

He was one of the kids who “made it,” but the place he made it out of was pretty nice, too. According to Madeline, a veteran schoolteacher, it was the kind of middle-class, multi-racial community where people know each other and got along, and all the parents seemed to work as a collective, fathers looking after each other’s kids on sports teams and families having each other over for picnics.

“We just had a good time,” she said. “You don’t look at colour, but it was very diverse.”

When he went off to college, however, Julius began to drift. The summer after his first year, in 1999 he began committing petty crimes.

“Being young, just wanting to have money, I got into shoplifting. I stole pagers. I stole things that I could sell,” he said from a jailhouse phone in the 2018 ABC documentary series The Last Defense, which detailed his case. “Wrong is wrong. I shouldn’t have done it. And I’m not trying to hide from anybody that I broke the law, because I have. But just because I broke the law does not make me a murderer.”

That summer, he reconnected with an acquaintance named Chris Jordan. They’d known each other from school and basketball, but Jordan never graduated and became affiliated with gang members, while Julius went off to university. Jordan, who had a car, would give Julius rides, and Julius had talked about taking his college entrance ACT test for him in exchange for money. He liked helping people, after all, and he needed the money, too.

Their paths would soon diverge once again: Chris would take a deal from prosecutors to avoid the death penalty in the Howell shooting and testify against Julius, and his old basketball buddy would head to death row.

The Red Bandanna

Two days after Paul Howell was killed, police located his GMC Suburban in a parking lot near a known chop shop, which dismantled cars of dubious origin and sold them for parts. The owner of the shop, Kermit Lottie, and Ladell King, known to police as a prolific dealer in stolen cars, were both professional informants for Oklahoma police. They traded information with officers in lenient charges or a tacit license to operate unimpeded.

Mr King claimed, as did his associate Chris Jordan, that Julius had confessed to killing Mr Howell and tried to sell his Suburban to Mr Lottie, who declined to buy the vehicle. The Independent was unable to locate Mr King for comment, including through public records searches.

Julius, meanwhile, has said he was with his family at home during the murder, eating spaghetti and playing the board game “Monopoly.”

“This is a life on the line,” his sister Antoinette told The Independent. “It’s an innocent life on the line.”

After being arrested, Julius countered that Chris Jordan had in fact confessed the murder to him after the fact, which Mr Jordan denied.

There had been a rapidly vanishing window, as police searched for a suspect, where Julius could have reached out and given his version of events. However, in the moment, as a manhunt stormed across the suburbs for Mr Howell’s killer, Julius was too afraid to act. Oklahoma, to this day, has the highest Black incarceration rate in the country, and Julius didn’t trust the system to protect him if he volunteered himself.

“You have to understand that the environment I grew up around, the people I grew up in around, you were not supposed to talk to the police,” Julius told the ABC documentary crew. “Bad things could happen to you or your family.”

Those bad things would find him and his family anyway.

“From my point of view, it was like half and half. There were some good cops and some bad cops,” Antoinette remembers of the area. “There were a lot of cops in the early ‘90s that were hellbent on taking young Black men, adding cases to them once they’ve been put in the system.”

Still, in her tight-knit neighbourhood, and in her own family, she knew plenty of law enforcement officers, who would be there at local sports games and other community events.

“I was under the understanding that the police were going to do their job and their job was to make sure that people were safe,” she continued. “I had never had really bad encounters with the police until the evening where they came to my house and they pulled a gun on me for the first time.”

Once police had Julius’s name, they began charging towards a resolution. Officers surrounded the Jones family home, hauling out Julius’s relatives at gunpoint and tearing through the house. Inside, in a crawl space, they found a gun matching the murder weapon, wrapped in a red bandanna.

It didn’t seem to matter that days before the murder, Julius had been photographed, during a mugshot for doing donuts in an empty parking lot, with buzzed short hair, not the kind of cornrows Chris Jordan had at the time, that would have stuck out from under a skull cap. It didn’t seem to matter that Julius’s prints weren’t found in the car. It didn’t seem to matter that the night after the murder, Chris Jordan asked to sleep over at the Jones house for the first time, where he slept in a bedroom near where the murder weapon was found, and that Julius’s family saw him seeming to skulk around upstairs. It didn’t matter that investigators’ case-making information came from a group of men with a vested interest, and an easy avenue, of avoiding police scrutiny.

Mr Jordan, through his attorney Billy Bock, denied any sort of framing took place. “It didn’t happen,” Mr Bock told The Independent. “Certainly, from my client’s position, it’s another way to spin the story to try to deflect responsibility. I completely understand why they’re doing what they’re doing. I just wish it was based on fact.”

Whoever placed the gun in the red bandanna and stashed it at the house, once it was found, police had a more-than-plausible conviction. They had their man. They weren’t going to turn back.

The community wanted resolution, and the prosecutors who depended on their votes each election wanted death.

‘This is still a nice town’

To understand the crackling current of fear that ran through the Julius Jones case, you have to understand Edmond, Oklahoma, the suburb where the killing took place, and the swaggering prosecutors who sought to avenge it.

It was one of numerous similar suburbs across the country, where numerous people moved en masse as cities were legally mandated to become racially integrated following the mid-century victories of the civil rights movement. Its population was wealthy, and more than 85 per cent white. The killing touched off an existential panic about whether the tacit promise of a place like Edmond was still intact. News coverage at the time played up the seeming contrast between small-town tranquility and city grit as all but a clash of civilisations, describing how gang elements may have “invaded the secluded area.”

“It’s senseless,” one resident told a local paper. “Why in my neighbourhood?”

After Julius and Chris were arrested, an Edmond police officer told local TV news, “This is still a nice town. This is still a safe place. That is why we so aggressively sought these individuals out.”

Back in Oklahoma City, Julius’ neighbourhood was split. Some began to ignore the Jones family. Others wrote letters of support and helped the family repair the damage police had done to their home during the search. Still others were totally aware of what happened even years later, as this all occurred before the world of Google and 24/7 news on social media.

“Among the community and among the teachers, I can only think of one parent who I’ve known over the years who thought Julius was guilty,” said John Thompson, who taught both boys at John Marshall High School.

But the man charged with prosecuting the case, Robert “Cowboy” Macy, had no such hangups about executing Julius Jones. Mr Macy, now deceased, was one of the five most prolific users of the death penalty in the country during his time as Oklahoma County District Attorney, according to an analysis from the Death Penalty Information Center. The self-styled cowboy wore boots and an old-fashioned string tie, and kept playing cards on his desk featuring his picture, on horseback, and factoids touting he was that the “nation’s leading death penalty prosecutor.” He also had a record of flagrant misconduct. Courts reversed nearly half of his death sentences for prosecutorial or policing errors. He once reportedly pushed an opposing attorney during a trial, and was ejected from a courtroom for reaching for a gun after a jury chose to acquit his targets.

Five days after the murder, Mr Macy, who commanded an outsized presence in the local media, said Julius deserved to die. A day later, the state’s largest newspaper endorsed his decision.

Both executions themselves and public support for them peaked in the late 1990s. Julius Jones, then, was accused of the worst possible crime, at the worst possible time, with the worst possible prosecutor if he wanted to stay alive. The finer-point questions around the police investigation, or the real Julius, were beside the point now. A Black teen had killed a white man, and that was enough.

“You’ve got such a classic story. A John Marshall honors student being charged with this murder in suburban Edmond,” Mr Thompson, the teacher, said. “The message behind this was, you were right to leave Oklahoma City and go to Edmond. Because look, even the best of ‘em, can commit a crime.”

Over the years, Mr Thompson has researched to write a history of policing in the area at the time of the Julius Jones case. He heard that internally, one of the mottos among the prosecutors was that “every inmate at Big Max [the nickname for a high-security Oklahoma prison] is guilty of the crime he was duly convicted of, or something else.”

‘I didn’t see justice’

Julius Jones’ trial proved even more calamitous than the police investigation that preceded it. His original public defender, an experienced trial attorney, died before the case entered the courtroom. Instead, a pair of inexperienced lawyers, one fresh out of law school and another who had never handled a death penalty trial, took over the case.

Kermit Lottie, Ladell King, and Chris Jordan all took explicit pleas or expected likely legal benefits to testify to the police’s version of events. Jordan’s deal was enough to avoid the death penalty and instead get a 30-year sentence. The jury was not made aware that Lottie and King had previously been police informants. Julius’ original public defender had asked for all evidence of any agreements between prosecutors and their witnesses for special treatment in this or other cases.

Mr Lottie, in an interview with The Independent, denied being a police informant or contributing to Julius Jones’s eventual death sentence.

“I never testified against that guy,” Mr Lottie said. “I never said a bad word against that guy ever. I never said nothing to prosecutors. I never said nothing. I don’t know the guy. I never met him.”

Court records reveal that Mr Lottie had previously served as a confidential informant in 1995, and sent a praise-filled letter to prosecutor Sandra Howell-Elliot, who was prosecuting Julius at the time, describing how he had helped other Oklahoma officials “get some big time evidence” in other cases, and asked for “a little help myself.”

Mr Lottie was facing federal drug charges at the time, and court records remain sealed regarding what went into his eventual sentence, which came down three days after Julius was sentenced to death. Edmond police asked federal officials for leniency in the sentencing due to Lottie’s status as a “key witness” against Julius.

Since then, he said people have shot at him and threatened his children because of his involvement in the case.

“I’m walking around with my back against the wall,” he said. “I’ve got family here. They threatened my kids and everything.”

Elsewhere, the green defense attorneys missed easy avenues that would’ve bolstered their case. They didn’t locate the mugshot that would’ve shown Julius’s hair wouldn’t have stuck out under a skull cap. They didn’t call anyone in the Jones family onto the stand, not even Julius himself. They believed, erroneously, that a jailhouse letter Julius had written to a girlfriend contradicted his alibi.

Instead, they rested their defense without offering one, and didn’t do much to impugn the original police testimony of Mr Jordan, which even the detectives who interviewed him acknowledged was erratic—contradicting itself on key facts like whether he heard gunshots, saw Mr Howell get killed, touched the gun in question, or slept at Julius’ house.

“What I saw in the courtroom, I didn’t see justice. I saw somebody wanting to get a win, and not the truth,” Antoinette said of the experience. The mismatch between the fierce confidence of the prosecutors, and their public defenders, was crushing.

David McKenzie, one of Mr Jones’s trial lawyers, did not respond to a request for comment, but has publicly acknowledged problems with the defense

The 12-person jury, 11 of whom were white, voted unanimously for the death penalty. In 2017, one of the jurors disclosed publicly that a counterpart said the trial was a “waste of time” and that police should “just take the n****r out and shoot him behind the jail.” The comments were reported to the judge at the time, but the juror remained on the panel, and Julius’s fate seemed sealed.

“It’s this never-ending nightmare’

Chris Jordan was released from prison early in 2014 and still lives in Oklahoma, where he lives largely anonymously and works as a labourer. He has written letters of apology to the Howell family for the role he pled guilty to, as the driver, in the carjacking that caused Paul Howell’s death. When he does communicate with the public, it goes through his father, then through his lawyer.

Julius Jones, meanwhile, has been waging a two-decade campaign to get his case reheard. Various state and federal appeals, claiming ineffective counsel and a biased jury, have all been shot down. Unlike most places, Oklahoma has a condensed appeals system where both fact-finding and procedural review processes occur essentially simultaneously. It’s vexingly difficult for those who felt wrongly convicted to both identify problems with their case and prove they would’ve matter at the same time. For most death row defendants, nearly all of whom are poor, there usually isn’t the money or the access for this kind of high-powered legal access. A bipartisan 2017 report from the Oklahoma Death Penalty Review Commission found that this arrangement “increases the risk that constitutional concerns,” like prosecutors withholding potentially exculpatory evidence, “will go uncorrected.”

A federal law, the Antiterrorism and Effective Death Penalty Act of 1996, further limited Julius’ options, since it requires federal appeals courts to give states great deference on capital cases. The law was inspired by the 1995 Oklahoma City Bombings and concerns bomber Timothy McVeigh would evade capital punishment. McVeigh was later put to death, following a series of state and federal cases, including one led by a charismatic Oklahoma prosecutor named Robert “Cowboy” Macy.

Most significantly, three different men—one of whom was facing a life sentence and another sentenced to death—none of whom were offered incentives or knew Julius Jones—came forward and said Chris Jordan had confessed to the Howell murder in jail, which his lawyers deny.

The fact that none of these questions were enough to get Julius another shot at justice weighed heavily on his family.

“It’s like this never-ending nightmare that you can’t wake up from,” Antoinette said. “The reality that he hasn’t come home yet, sometimes it’s a little suffocating. It’s almost like being buried in a cement tomb. You can’t breathe but you need to survive. You wake up and you still realize I’m still in this hell.”

Sometimes, she gets anxious in her day-to-day life, trying to remember every detail so she can explain them to Julius during visits. She prays to God he can experience fresh air again before he dies.

The reality that that might never happen began to set it for everyone as each successive appeal flamed out. Julius tried to keep strong and keep praying, but occasionally let down his nurturing demeanour and revealed to his family he was struggling. He spends 23 hours a day in his cell, and hasn’t hugged his mom since he was 19.

“He was resigned to being on death row, no one would ever know his story,” said Cece Jones-Davis, a leader of the growing Justice For Julius movement. “He was ready to be executed so that his family could be free.”

The exoneration will be televised

His death date was even scheduled, before a series of botched executions in Oklahoma inspired a temporary moratorium on the practice in 2015. That was the first of many fortuitous developments that revived the Jones family’s hopes.

In 2016, a group of federal public defenders took over his case and began charging hard for any remaining appeals. Not long after, a film crew from ABC began producing The Last Defense, a true crime series about Julius and other cases of potential wrongful conviction, chosen from among hundreds of potential stories.

More so than any legal process, the documentary, produced by actress Viola Davis and shown to millions, is what brought Julius’s case back to life, and amplified his case into a cause.

“Julius would still be sitting in the dark and nobody would know his name,” Ms Davis, an Oklahoma-based activist, said of the show’s impact. “Community is stronger than these systems that we’re fighting. These systems are monstrous, don’t get me wrong, but when people see that something is wrong and we want to do something about it, we’re ready to commit, that’s a force, that’s really powerful.”

Soon celebrities like Kim Kardashian, NBA star Blake Griffin, and late night TV host James Corden were championing the burgeoning Justice for Julius campaign.

Neighbours began apologizing to the Jones family for not sticking by them after seeing the ABC show. It was the first time many in the community learned about what happened to Julius at all. Some people thought he had gone overseas to play basketball.

A Change.org petition on behalf of Julius has more than 6.3 million signatures, and news organisations began highlighting the case once again. It was the near exact inverse of how he got convicted in the first place: the public and media were now clamouring for careful appeal, not hard justice.

In 2019, Julius’ public defenders filed a clemency petition with the state. Soon after, his campaign got another boost from Represent Justice, an advocacy group created along with the release of the 2019 film Just Mercy, which tells the story of legendary legal advocate and Equal Justice Initiative founder Bryan Stevenson. It was becoming clear that the power of narrative was the final missing element, maybe the only thing possible, that could’ve pulled Julius out of his slow-moving, all-obliterating legal limbo.

“One of the things that we’ve realised is that people are connecting to stories more than they are to facts and statistics,” Represent Justice CEO Daniel Forkkio told The Independent. “They are empathetic and motivated and energized around awareness of a story in the way they’re not around other things.”

Wrongful conviction, and the innumerable barriers young Black men face in getting proper representation, were becoming nationwide topics of conversation. It seemed, finally, the public conversation around criminal justice, and what that meant as applied people like Julius, had turned away from “superpredators” and back to something like human decency.

On 13 September, 2021, the Oklahoma Pardon and Parole Board recommended 3-1 that the governor commute Julius’ sentence, the first time a commutation was urged for a death row inmate in state history.

“Personally, I believe in death penalty cases there should be no doubts,” board chairman Adam Luck said of the decision. “And put simply, I have doubts about this case.”

But the system, and many of the same individuals that sought death for Julius, weren’t about to throw away their hard-fought conviction. A week later, he was given his execution date.

The board voted again on 1 November to recommended commutation for Jones. Jones’ attorneys praised the outcome at the time. Julius is out of legal appeals, and clemency is the final forum through which he could get off death row.

“The Pardon and Parole Board has now twice voted in favor of commuting Julius Jones’s death sentence, acknowledging the grievous errors that led to his conviction and death sentence,” Jones’s public defender, Amanda Bass, said in a statement following the decision. “We hope that [Oklahoma] Governor [Kevin] Stitt will exercise his authority to accept the Board’s recommendation and ensure that Oklahoma does not execute an innocent man.”

On 15 November, family members waited outside of Gov Stitt’s office to plead their case. The governor did not ultimately meet with the family, and instead sent a spokesperson to relay that the governor is following a “process”.

Justice for Paul Howell

The Howell family, which did not respond to requests to participate in this story, has largely kept a low profile since Paul’s murder. They maintained that Julius was the correctly identified killer, but eschewed the spotlight.

As the Justice for Julius movement began gaining steam, they launched a campaign of their own, called Justice for Paul Howell in the news and on social media. Now, the battle over the case had moved into the realm of public relations, with slick websites aiming to take apart the other side’s points before the public jury. The Howell family felt that high-profile celebrity figures and overweening national news outlets had hijacked their story to advance a political agenda. They began to feel, as Julius had felt before them, that the system and the media were arrayed against them. This is despite the fact that they, in the legal sense of the word, had continued to win, and their position was supported by current and former officials. Leaders like the current Oklahoma Attorney General and his predecessor argued that after numerous failed appeals, before more than 10 appellate judges, and a 2018 DNA test on the red bandanna that was a disputed match to Julius Jones, all this should be enough to let this case—and the Howell family—finally rest.

“These celebrities and influencers don’t bother to reach out to us about it. I think the thing that is most frustrating about all this is you influence your followers. If you’re a celebrity, an influencer, an athlete, you have a lot of followers who look up to you,” Rachel Howell, Paul’s daughter, told Oklahoma’s KFOR, the day Julius was recommended for commutation. “I think the only thing I want these celebrities to know is to think about the victim’s family. Take the time to at least look at both sides. You don’t have all the information.”

“This is David versus Goliath,” Clayton Howell, Paul Howell’s nephew, added.

They said they were “devastated” by the commutation recommendation, calling the legal process “in no way fair.”

Sandra Howell-Elliot, one of the prosecutors who convicted Julius, took the rare step of coming out of retirement to argue at the commutation hearing that he still deserved the death penalty. She did not respond to a request for comment from The Independent.

Jerry Bass, the judge who presided over the original trial, began posting on Facebook in support of the execution.

David Prater, the current district attorney, has sought to remove two members of the Pardon and Parole Board, arguing their criminal justice reform work makes them biased, after a similar request was denied at the state Supreme Court earlier this year. He did not respond to a request for comment from The Independent. All eyes are now on Oklahoma governor Kevin Stitt, who has said he’ll make his decision after the hearing later this month.

The case has arrived at the stage now, in other words, where no one—not the victim’s family, nor the accused, nor the officials who sentenced him to death—feels like the process is working as it should. But, after more than 20 years, a resolution is coming soon, one way or another.

‘Not everybody gets that chance’

If Julius does get executed, Ms Davis-Jones thinks we’ll look back at it one day like the 2020 murder of George Floyd by former Minneapolis police officer Derek Chauvin, or the widespread lynchings of Black men before that, as a travesty of historic proportions.

“We are at risk of revisiting the kind of shame that happened,” she said. “People should care because we’re living in the era of George Floyd. We saw in horror what happened to that man, how the system had its knee on George Floyd’s neck. We see now that the system has its knee on another man’s neck.”

If Julius lives, it will mark the ascendance of a new kind of coalition, where Black activists and entertainers, along with the legal advocacy establishment and certain parts of the liberal media, were able to marshal enough power to pull a life back out of the execution chamber. Nearly one person is exonerated for every 8.3 people who are executed in the US, and people in North America, disproportionately people of colour, have been executed for capital crimes since 1608. Saving even one Black life from execution, then, is historically significant.

Of course, the Jones family won’t know peace until Julius is off death row, but they are grateful, after twenty years of fighting, that the world finally wants to hear what Julius has to say.

“That’s what we’ve been fighting for the whole time,” Antoinette said. “For him to be able to speak on his own behalf...Not everybody gets that chance.”

What remains to be seen is whether enough time has gone by that the right people will listen.

This article was amended on 13 October, 2021. It previously inaccurately stated that one in nine people on death row were later found to be innocent. The study referred to found that for every 8.3 people executed between 1972 and this year, one person had been exonerated. However, far more people are sentenced to death than are ever executed. Around 2 per cent of people on death row during that period have later been exonerated.

The Independent and the nonprofit Responsible Business Initiative for Justice (RBIJ) have launched a joint campaign calling for an end to the death penalty in the US. The RBIJ has attracted more than 150 well-known signatories to their Business Leaders Declaration Against the Death Penalty - with The Independent as the latest on the list. We join high-profile executives like Ariana Huffington, Facebook’s Sheryl Sandberg, and Virgin Group founder Sir Richard Branson as part of this initiative and are making a pledge to highlight the injustices of the death penalty in our coverage.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments