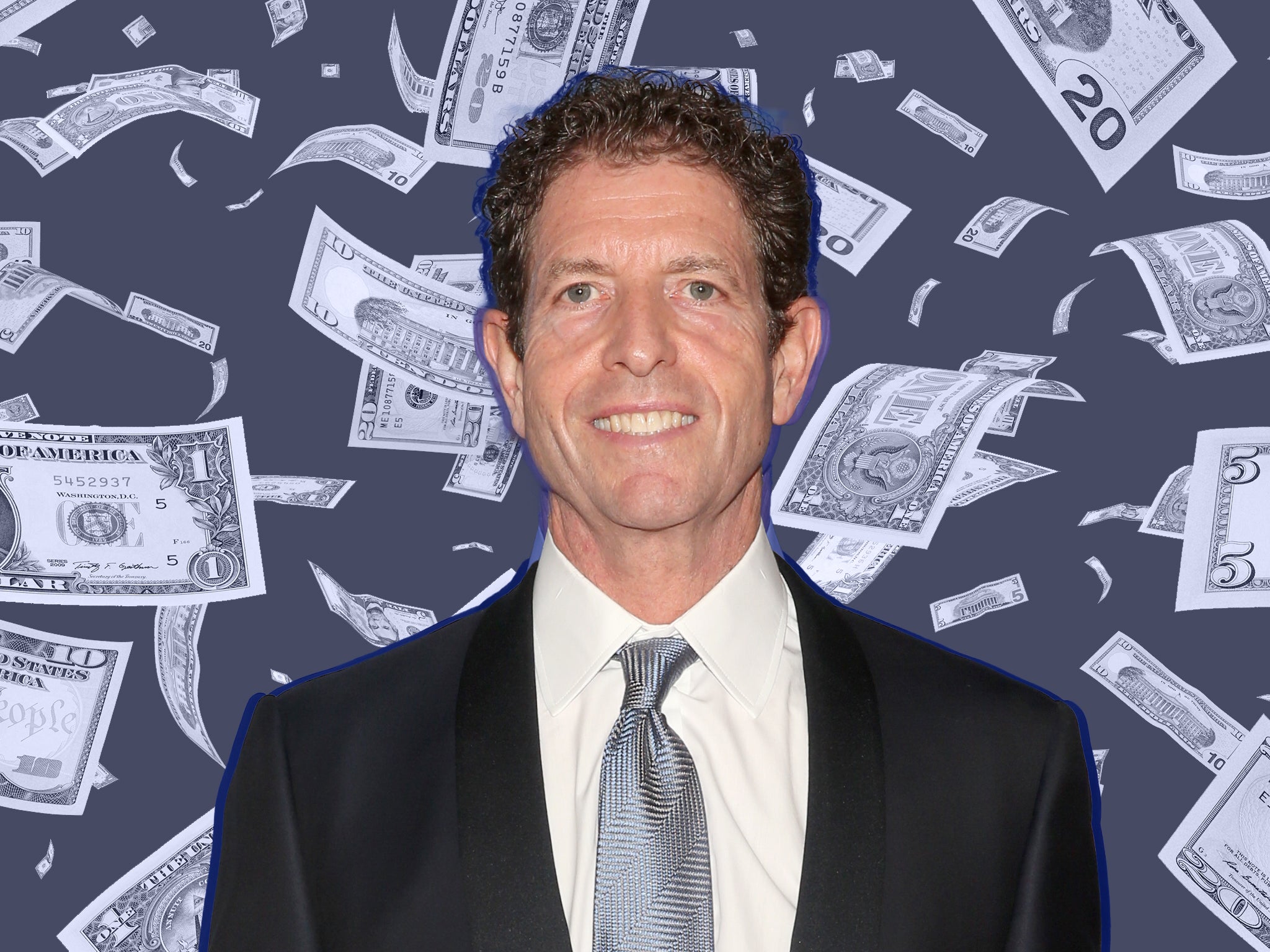

War on Wall Street: Why billionaire Daniel Och is suing his former hedge fund for paying his own protégé too much

The New York mogul left his own hedge fund after a massive African bribery scandal. Now he’s fueding with the man he once groomed as his successor, Io Dodds reports

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.In 2016, the billionaire hedge fund manager Daniel Och agreed to pay nearly $2.2m to settle charges that he had broken US laws against bribing foreign government officials.

Och, US regulators said, had been warned by his own lawyer and his chief financial officer not to do business with an "infamous" Israeli businessman who regularly played bribes to public servants of the Democratic Republic of Congo, but did so anyway.

The settlement – whose findings Och did not admit or deny – came from a major investigation into what regulators described as "complicated, far-reaching" bribery schemes by Och's investment firm Och-Ziff Capital Management to secure special access from officials in Libya, Chad, Niger and beyond, resulting in $413m of fines for the company, a jail sentence for one of its executives, and the reported loss of one third of its assets.

Now Daniel Och is mounting a lawsuit against his former firm, today known as Sculptor Capital Management, accusing it of poor corporate governance.

Yet rather than anything relating to the firm's chequered past, Och's legal case stems from a more pecuniary grievance: the high pay of its new chief executive James Levin.

In a complaint filed with the Delaware court system last month, lawyers for Och and his co-plaintiffs wrote that Sculptor's "less than mediocre" performance and annual revenue of $626m "cannot possibly justify" Levin's 2021 compensation package of $145.8m – which the lawsuit alleges is more than Apple's Tim Cook or JPMorgan Chase's Jamie Dimon.

Since his appointment in April 2021, the lawsuit claims, Levin has "devoted himself to entrenching his position at the company, shaping the board of directors, and wielding that resulting leverage to extract ever-escalating pay packages".

Och remains a major shareholder in Sculptor, with 14.4 per cent of its voting power, according to Reuters, and he mounted his lawsuit alongside four other major shareholders in the firm.

The suit claims that Levin's pay in 2021 was 17.7 times larger than the median pay of chief executives at equivalent firms, despite Sculptor's share price falling from its summer peak by more than 25 per cent by the end of the year (it's now down by 67 per cent).

Sculptor quickly shot back: "Mr Och's filing is misleading and full of falsehoods that present a grossly distorted view of Board governance at the company. We look forward to setting the record straight through the legal process...

"The acrimonious separation from Mr Och resulted in a grudge against the company and its leadership that he continues to harbour."

Indeed, this is the latest in a long-running drama between Och, Sculptor and its new CEO. According to reports, Levin joined the company in 2006 and was groomed for years as Och's protégé and intended replacement.

Och was even said to have earmarked Levin, then only 33 years old, for an eye-watering pay package of $250m, including 39 million of Och's own shares.

But around Christmas 2017, Och reportedly changed his mind and froze Levin out, leading to a different chief executive to be brought in from Credit Suisse to soothe relations between the two moguls.

The dispute caused the departure of William Barr, later to become famous outside of Wall Street as Donald Trump's attorney general (until he finally resigned following the 2020 election after saying publicly that it was not stolen).

"I rode it out because of [my colleagues' and clients'] faith in me," Levin told Institutional Investor in 2020. "Asset management is always about the team and the people willing to back the team."

These were dark times for Sculptor. When Levin took the throne, the company was in its sixth straight year of losing more assets than it gained as clients pulled a total of about $30bn out of the fund in the wake of its bribery scandal.

Under Levin's tenure that trend reversed, with the first quarter of 2021 bringing Sculptor's first net inflow of assets since the scandal broke. By the end of the year, however, its profits lagged behind investors' expectations, even though its assets had increased.

This February, one of Sculptor's board members resigned over what he described as "governance failures" that led to Levin being given a "staggering award" despite "numerous warning flags".

The board member, J Morgan Rutman, has close ties to Och, who originally appointed him and now employs him as president of his family wealth management office.

Rutman particularly took aim at the shares that Levin received as part of his 2021 compensation package, which he claimed gave the chief executive a bigger vote over Sculptor than the founders of rival investment companies such as Blackstone and Apollo enjoy over their own creations.

Sculptor said at the time that Rutman's letter contained many "inaccuracies" and "baseless assertions", arguing that all its independent directors except him believed Levin's compensation was in shareholders' best interests.

Regardless of the lawsuit’s outcome, economists and activists have long argued that American chief executives as a class have too much power to set compensation for themselves and other senior executives.

A report by the left-leaning Economic Policy Institute (EPI) last year found that average salaries for the chiefs of the top 350 US firms had soared by by 1,322 per cent since 1978, compared to18 per cent for the typical American worker.

Advocates say these pay awards reflect fair market rates for exceptional talent, and point out that, since many CEOs have their salary supplemented by stock grants, much of the increase in their total pay comes from the rising value of their own shares.

However, the EPI report notes that CEO pay also outstripped stock market gains – the S&P 500 index grew by 817 per cent in the same time period – and argues that these same stock awards give chief executives more voting power to keep salaries high.

“High CEO pay reflects economic rents—concessions CEOs can draw from the economy not by virtue of their contribution to economic output but by virtue of their position,” said the EPI in a previous report in 2017.

“CEO compensation appears to reflect not greater productivity of executives but the power of CEOs to extract concessions.”

Perhaps that is why, as of May 2021, a record number of S&P 500 companies saw their shareholders reject executive pay packages in non-binding votes.

“Most studies show that CEO pay and performance are uncorrelated or negatively correlated, meaning the more you pay the less you get,” said Steven Clifford, author of The CEO Pay Machine, in 2017. “CEO pay is as market-driven as were the salaries of Soviet commissars.”

This article was updated at 9pm BST on Wednesday 14 September 2022 to add extra material.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments